Atulya Pandey co-founded a tech startup in New York, but lost the visa lottery. Now, he is attempting to run his U.S. business from Nepal, according to the New York Times. Last year, Yasin Unlu, an employee at Llamasoft, a Michigan-based IT company, lost the visa lottery. He spent a year working at the company’s London office. This year, he won the lottery, so he will move back to Michigan, according to Crain’s Detroit Business.

In 2015, Disney IT worker and U.S. citizen Leo Perrero was laid off. He and the other 249 laid off IT employees have been blacklisted. For a year, none of them can apply for contract work or employment with Orlando’s largest employer, Perrero said. Training an H-1B worker was a condition of his severance.

Perrero said that if he had not trained the new worker, he would have lost 90 days of pay, health insurance, pension and 401(k), as well as four weeks of pay from severance and 10 percent of his annual salary for a “stay bonus.”

software company prefers recruiting and growing local talent.

Stories like these are at the heart of the controversy over the H-1B program. Authorized in 1990, the program was designed to give employers a bridge to the global workforce, but only in cases where local workers did not possess the skills needed. With H-1B visas, employers can hire “nonimmigrant aliens as workers in specialty occupations or as fashion models of distinguished merit and ability,” according to the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL). H-1B visas are held by employers. To acquire an H-1B, the worker must have an employer-sponsor.

Overlooking the fashion model distinction, the H-1B debate centers on the term “specialty occupations.” A specialty occupation “requires the application of a body of highly specialized knowledge and the attainment of at least a bachelor’s degree,” per the DOL. For a while now, many workers and activists have questioned the “distinguished merit and ability” of H-1B visa workers. On the other hand, many businesses and visa workers question why the U.S. government would send talented foreign workers back to their home countries when their skills are needed here in the U.S.

The cap and the lottery

The 65,000 H-1B visa cap applies to foreign workers with a bachelor’s degree or above awarded by a non-US institution. (In the early 2000s the cap was raised for several years to 115,000 and then to 195,000). An additional 20,000 visas are set aside for foreign workers who have earned master’s degrees from U.S. institutions. Then, there are the cap-exempt organizations, universities and non-profit or governmental research organizations. In 2008, about 129,000 visas were issued, according to a 2011 Government Accountability Office report.

In most years, the number of applications exceeds the caps, so visas are awarded via a lottery system, “a computer-generated random selection process,” according to the GAO.

Temporary worker to resident innovator?

The H-1B is a critical stepping stone for bringing the world’s best technology entrepreneurs and innovators to the U.S., say supporters of raising the cap. And, they say, if these workers cannot enter or stay in the US, then they will take their skills to another country.

Workers seeking an H-1B must have an employer sponsor their visa. However, the GAO report states that foreign entrepreneurs not employed by a separate company are ineligible for the H-1B. “For example, for the earliest stage ventures, when the person who needs the H-1B visa is the entrepreneur, there is sometimes no ‘firm’ in existence yet that can meet legal criteria for employing H-1Bs,” reports the GAO.

According to lawyers interviewed by the GAO, some of these entrepreneurs had to move their projects abroad or shut them down entirely. This loss of potential prompted some of the businesses interviewed by the GAO to suggest the creation of an entrepreneur visa.

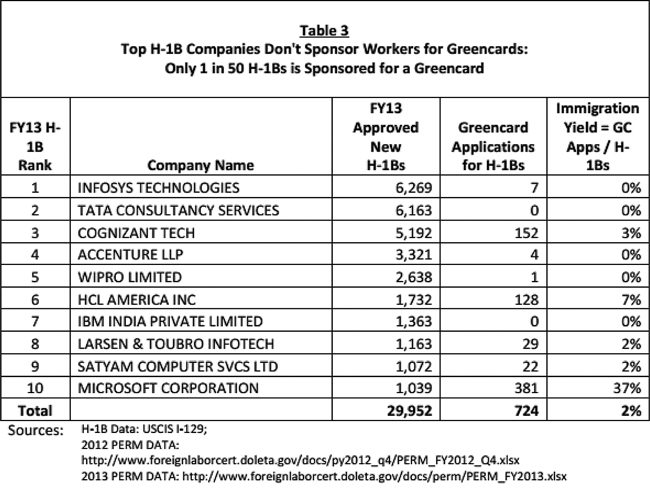

For workers on an H-1B, the visa is good for a maximum of six years (two three-year terms). But workers can apply for permanent residency (also known as a green card). As with the H-1B, they must have their application sponsored by an employer. The path from temporary worker to permanent resident can be long and is definitely expensive.

Once the green card application has been submitted, workers stay in the U.S. on extensions until a green card decision is made. If the worker is from India, China, or Mexico, though, the wait time is longer, reports the GAO. A worker from one of those countries “could remain in the United States for over a decade before obtaining a green card,” according to the GAO. As for the expense, filing an H-1B petition can cost between $2,300 and $7,500 and combined with the green card process, can be up to $16,000, states the GAO.

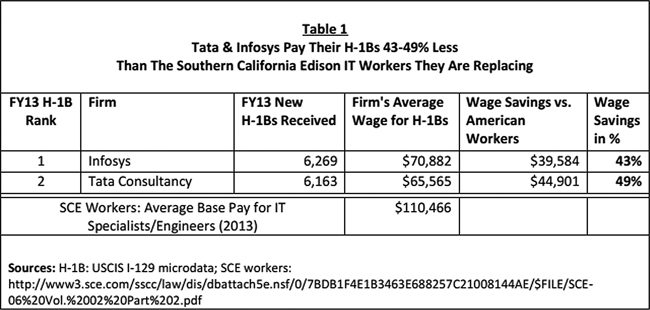

Proponents of raising the cap say immigration is the end goal. However, opponent companies point out that large IT staffing firms take the majority of visas each year, and they apply for few, if any, green cards. In fiscal year 2013, the top two visa takers were Infosys and Tata Consultancy Services. In that year, Infosys took 6,269 visas; Tata took 6,163, according to Ron Hira of the Economic Policy Institute. In that same year, Infosys applied for seven green cards, and Tata for zero, reported Hira.

The H-1B market

Opponents of raising the cap often point to the large IT staffing and solutions firms (like Tata and Infosys) as being the problem, since they have the resources to apply for a large number of visas and thus a greater chance of winning the visa lottery. (The guy who buys 100 lottery tickets has a better chance of winning than the guy who buys just one, for example).

The business of a staffing firm is providing labor to client companies. Sometimes that labor is provided in the U.S.; in other cases, it is located overseas. In some cases, the labor is initially provided in the U.S. and is then transferred overseas. Infosys and Tata are both based in India. In 2012, Tata’s workforce was over 90 percent Indian, according to the company’s own report, which was published by Patrick Thibodeau of Computerworld, an online IT magazine. In fiscal year 2014, 66 percent of all new visas went to workers born in India, according to the Department of Homeland Security’s 2014 report titled “Characteristics of H-1B Specialty Occupation Workers.”

Rather than thinking of IT staffing firms as purveyors of inexpensive labor, Adams Nager contends they capitalized on a different market. Nager is an economic policy analyst with the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation. From his perspective, large IT staffing firms provide expertise on navigating a complex visa process. The process involves two applications, three governmental agencies, cumbersome documentation, and, as noted above, thousands of dollars per petition. Add to these investments of resources and time, the reality that the whole thing culminates in a lottery—only a chance at getting the visa.

Of late, two highly publicized cases have grabbed the attention of the IT world, if not the general public. In 2014, Disney informed 250 of its IT employees that they would be laid off. But their work was not eliminated. Instead, it was handed-off to contract workers from HCL, an IT staffing firm based in India. In that same year, Southern California Edison (SCE) announced that it would lay off 400 employees. Their work has been transferred to contract workers from Tata and Infosys. (In either case, it is not clear how many replacement workers were hired).

Disney and SCE are “in their own category,” said Nager. When looking at abuses that can take place within the program, “there haven’t really been many other cases like that, that are so clear cut,” he said. Yet, this case yielded no negative consequences for Tata and Infosys. The DOL investigated a complaint filed on behalf of the SCE workers and found no wrongdoing.

There is so much focus on the cap that there is little discussion of the flaws within the H-1B program’s design, said Hira. “Restricted agency oversight and statutory changes weaken protections for U.S. workers,” reported the GAO in 2011. Echoing those concerns, in March 2015, Hira testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee: “There are no requirements to demonstrate a shortage of Americans prior to hiring an H-1B. Employers do not need to recruit American workers for a job filled by an H-1B. In fact, a job can, and often is, earmarked for an H-1B worker.”

Developing innovators at home: Nexient

Nexient builds software using an “agile” business approach, said Mark Orttung, the company’s chief executive officer. The term refers to a “very collaborative” way to “rapidly build software,” he said. With an agile approach, developers, testers, and business staff collaborate frequently every day. In a typical offshore model, though, these teams may meet only once a week and are separated by multiple time zones, said Orttung. That means they may only have one hour a day of overlap. (Bangalore, India is 10.5 hours ahead of Eastern Time and 13.5 hours ahead of Pacific Time).

“There’s always a million little details that you need to collaborate on when you are building great software,” said Orttung. The agile approach means that the business people, developers, and testers are in close proximity. Not necessarily in the same building, but within a few hours of each other. “You can bridge distance much better than you can bridge time zones,” said Orttung.

The agile approach can be done by large staffing firms who hire H-1Bs, but Nexient has decided to recruit and grow local talent. Although its hub is in Silicon Valley, the rest of its offices are in the Midwest region (Ann Arbor and Okemos, Mich., and Kokomo, Indiana). It invests much time and effort in recruiting not only new graduates but also experienced professionals and self-taught coders.

At the college level, Nexient focuses its recruitment efforts on 20 Midwest universities across five to six states in the region, including Eastern Michigan University, Michigan Technological University, and Western Michigan University. “We get fantastic people out of the 20 colleges we recruit from,” said Orttung. These new graduates undergo a training program at Nexient, so they can “become really solid” engineers, developers and testers, said Orttung.

Nexient also focuses on hiring more experienced workers who have project and engineering management experience or who have an expertise “which only comes with years of experience,” said Orttung. Creating teams that have experienced professionals as well as new graduates is “a better way to build software,” said Orttung.

Some of their best recruits, said Orttung, have been those who hail from non-technology majors and professions. These are people who have taught themselves to code and program in their off-hours, he said. They have made a “habit” of continuous learning, and that mentality serves them well in the technology industry, said Orttung.

None of which is to say that Nexient does not hire H-1Bs. They do, although visa workers make up less than 15 percent of their staff, said Orttung. Typically, Nexient hires H-1B workers if a client project requires “a fairly niche kind of tech, and the only people you can find are here on H-1Bs,” he said, and, occasionally, when a graduate from a U.S. university has a unique specialty. Typically, the company sponsors these workers for green cards, so most of them become part of the growing domestic talent base.

Nexient’s daily price for a developer is higher than that of an offshore company. But Nexient is not competing on price, said Orttung. Nexient’s unique value lies in its ability to deliver context and locality. Nexient staff use the products and services that their clients sell; they shop in their clients’ stores and sign up for their phone plans, he said.

That context is invaluable when developing software for these companies. Additionally, Nexient teams can work together throughout the day because they are within three hours of each other. Those advantages mean that “we have a much, much lower amount of re-work that we have to do and that becomes really a critical piece both in terms of the quality of what you get as well as in time to market and ability to move quickly to keep competitive,” said Orttung.

Nexient’s clients include Fortune 500 and mid-market firms and most have used the offshoring model. Now, those clients want a different approach, “for at least a portion of their portfolio,” he said. “A lot of the IT side of big companies are hearing from the business side that they’re not happy with the results they’re getting currently,” said Orttung. “When they hear about what we’re doing, it really resonates,” he said.

Understanding the H-1B debate is no comfort to those whose lives hang in the balance: American IT workers and H-1B visa workers. Both groups sit at the center of the storm with little power to do much more than hang on. But, if Nexient’s model can become the standard, perhaps there will be some hope for both groups.