Drive the roads of America and you’re sure to find a variety of chain restaurants, with signage familiar to just about anyone with an appetite and the need for familiarity.

But among the independent restaurants, there’s a sense of charm and story along with the good eats.

Such is the case with the Bavarian Inn in Frankenmuth, Mich., one of the nation’s largest and oldest independent restaurants.

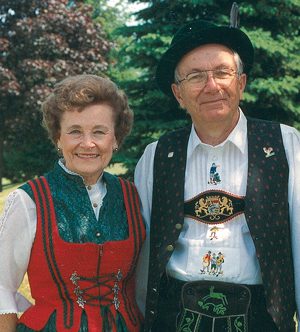

When the opportunity arises to sit down with the 95-year-old matriarch of the William Zehnder family, owners of Frankenmuth’s Bavarian Inn Restaurant and its adjacent Bavarian Inn Lodge, the answer of course is a resounding yes.

But talking with Dorothy Zehnder – who still at that wonderful age works six days a week in the Bavarian Inn’s kitchen and typically bakes in her own home on the seventh, often to the delight of great-grandchildren – presents something of a quandary when it comes to telling her story.

Is this a story about Dorothy, a two-time cookbook author and clearly the one that employees, many of them family members, turn to for counsel if not direction on key business decisions?

Or is it more the story of a family, with Dorothy’s late husband William “Tiny” Zehnder playing a key role in the vision that would eventually transform the town—“Bavarianizing” it, as Dorothy describes it—into one of Michigan’s most popular tourist destinations?

And then there’s the story about how a family like the Zehnders actually works together, the values and common sense principles that have obviously knitted them together over generations, a story from which other family businesses could borrow a page.

It turns out it may be a bit of “all of the above.”

But let’s start from the beginning.

In the case of Dorothy Zehnder, the opening scene is that of a teenager who is working as a waitress at Fischer’s Hotel, itself a family run business that was across the street from a restaurant run by the Zehnder family, where one of their sons, William, Dorothy’s future husband, worked while he wasn’t farming on acreage across from the nearby Cass River.

As was the case in those days (and possibly even today), those who worked at one enterprise would socialize with those at the other and that was the case with Dorothy and her future husband, although as Dorothy tells it, it wasn’t love at first sight.

Perhaps not even close.

“We didn’t start dating for probably a year after we met,” she recalls.

The family legacy begins

But romance did eventually bloom between Dorothy and Tiny, who married in 1943, the start of a relationship that ended only with his passing in 2006 and which produced three children—Judy, Roxie and Bill—two of them involved in the business today.

Dorothy quit her job at Fischer’s when she had Judy, her first child.

Tiny, whose father, William Sr. had first begun running Zehnder’s restaurant in 1928, continued in his management role.

Then the third-generation owner of Fischer’s decided to sell, a pivotal moment that changed everything for the Zehnder family.

It was Dorothy that first put the bug in her husband’s ear, although Tiny balked, the obvious reason being the lack of resources. Even tapping the family wouldn’t be enough, it was thought, to pursue the acquisition.

And that was that. Until it wasn’t.

Elmer Fischer, grandson of the original owners, came back to the Zehnder clan, essentially making it clear that if they didn’t buy, someone else would, not exactly an ultimatum, but a clear message nonetheless, that having someone they didn’t know doing business across the street could be much worse than any immediate financial pressures that would result from the purchase.

The Zehnders agreed to pool their funds to purchase Fischer’s, with Tiny and Dorothy moving over to run the enterprise in 1950. And just as Tiny was chosen to run Fischer’s, his brother, Eddie, was selected to run Zehnder’s Restaurant. In 1985, ownership changed, with the Eddie Zehnder family owning and operating Zehnder’s and the Tiny Zehnder family doing the same with the Bavarian Inn properties. The two businesses still sit facing each other across Main Street, as they’ve done for for more than 100 years.

“Things became too big,” says Dorothy of the combined business, “especially when the Bavarian Inn Motor Lodge was built.”

It didn’t take long for Tiny to retire from farming, although he did begin talking about what eventually transformed not just their business, but the entire Frankenmuth community.

Dreaming of Bavaria

“He was a dreamer,” says Dorothy today of her late husband, referring specifically to a “Bavarianization” of Frankenmuth that Tiny began with a major addition and eventual rebranding of the property, coupled with a town-wide Bavarian Festival that began in 1959 and which continues even today.

Dorothy admits that those early years—between their purchase of the property in 1950 and the addition—included some lean periods, such as the time right after the purchase from the Fischer family.

“There was a whole year when we couldn’t do any remodeling because there was no money,” she noted. “The place was run down and we had to repair the flooring in the front and there were a lot of repairs to do in the kitchen.”

“There was a whole year when we couldn’t do any remodeling because there was no money,” she noted. “The place was run down and we had to repair the flooring in the front and there were a lot of repairs to do in the kitchen.”

And then there was the conversation she and Tiny had after having spent the first six months working together.

“We were working together 24 hours a day, seven days a week and Tiny knew that wasn’t something that could continue. We needed to change that.”

For Tiny, the choice was simple: Dorothy could take her choice of working the office, the bar, the front of the house (greeting guests) or the kitchen.

“When I chose the kitchen, he said ‘good, I didn’t want to do that anyway.’”

It was the beginning of what became a 63-year partnership that ended with Tiny’s passing in 2006.

“We had our ups and downs, but he took care of the overall planning and I took care of the kitchen. He didn’t interfere with me and I didn’t interfere with him,” says Dorothy.

While it may be hard to believe now, given the popularity of the Bavarian Inn Restaurant and Bavarian Inn Motor Lodge, there was a point when the restaurant, still under the Fischer brand, was teetering on the brink.

The so-called Eisenhower Recession, an eight-month period from August 1957 to April 1958, resulted in the restaurant losing money and the business might very well have closed, had it not been for a decision to “double down” on Tiny’s vision of transforming the entire town, starting with the restaurant on which the young Zehnder family had staked their business future.

Tiny reached out through a magazine advertisement, ultimately agreeing with what appears to be the single condition under which the architect would work: “It has to be Bavarian. That’s all I do,” Dorothy recalls of the conversation that led to the work done on the restaurant.

“He said ‘do it,’” recalls Dorothy.

And that was that.

When that occurred, Dorothy embraced the new concept with her usual vigor and enthusiasm, but not without realizing the challenges involved for someone who had never before cooked in that style.

“I had to learn,” she says. “It’s surprising what you learn when you’re forced into it. I had to do all the research and come up with recipes and just go with it.”

Gaining momentum

To celebrate the 1959 opening of the Bavarian Room (ultimately the Fischer name was dropped and the name Bavarian Inn Restaurant was adopted), the Tiny Zehnder family organized a week-long “grand opening” that caught on quickly, becoming the annual Bavarian Festival, an event that continues today.

Tiny’s idea to “Bavarianize” the restaurant, Frankenmuth and even themselves!

Just two years later, the first Bavarian Festival Parade was held, attracting some 10,000 people. In 1962, the Frankenmuth Civic Event Council was chartered to run the Bavarian Festival, distributing funds raised to support three annual collegiate scholarships and cultural exchanges between Gunzenhausen, Germany, and Frankenmuth.

A few years after that, Tiny Zehnder commissioned an impressive 50-foot glockenspiel tower, featuring a 35-bell carillon that can be heard for miles around the town.

Built in Germany and then disassembled and shipped to Frankenmuth for reassembly and installation in October 1967, the glockenspiel features specially cast bells. Built in the traditional Bavarian style architecture, the tower can be seen from roads leading into Frankenmuth from the south.

It became an instant Bavarian Inn landmark with its revolving figures that depict the legend of the Pied Piper of Hamelin (spelled Hameln in German).

Even that wasn’t enough for Tiny Zehnder, who extended his vision by donating dozens of cupolas to businesses throughout the community. He even donated a roof treatment to the fire hall, all with the view to evoking a Bavarian theme.

Heading a family business now into its fourth generation, Dorothy has ceded much of the day-to-day management to a team led by her son Bill.

But she has fond memories of working over the years with grandchildren (she has four in senior management at the Bavarian Inn enterprise) who, along with her children, provided a kind of continuity in a family that literally grew up in the business.

“Every Friday and Saturday night they had to work,” says Dorothy. “At least I knew where they were and I’m pretty confident that Bill [her son] raised his kids the same way.”

Dorothy says the positive relationship she has with her grandchildren usually began in the kitchen.

“They all started in the kitchen,” she says, referring specifically to Amy, Bill’s oldest daughter, who at the age of 11 was working side-by-side with her grandmother.

“That’s what they called me—Grandma—but sometimes they called me Dorothy. According to them, that was because sometimes I didn’t respond when they used Grandma.”

Friendly competition that benefits all

Today, Dorothy and her clan remain friendly with their competition, perhaps because the vision of her late husband was what led to many of them being able to share in the prosperity of the Frankenmuth he envisioned.

At one point, there were just three restaurants locally. Now there are about 30, most of them tracing their lineage to the “Bavarianization” of the community.

Dorothy says throughout her career she has learned to embrace the kind of mistake that her husband Tiny pointed out as being the ultimate source of growth.

“If things didn’t turn out, we’d try something else,” she added.

A litany of family stories Dorothy is fond of telling includes that of her son Bill, who arrives when this story is being told.

“Bill was nine months old when I’d first bring him to the restaurant while I was working,” says Dorothy. “I’d bring him along and put him on a cart, giving him some cheap pots to play with. He could entertain himself for a long time and when I’d go to the basement, I’d push him there and he’d continue to play.”

Balancing work with duties at home, Dorothy remembers having breakfast with her family before heading to the restaurant. “At about 3:30 I’d go home so I was there when the children were there. You can hire a nanny but it doesn’t replace the role of a mother.”

She also recalls her son struggling with spelling in the sixth grade and how her husband “solved” the problem—by promising young Bill he would take him duck hunting if he got an “A.”

“He doubled down on his spelling, studying morning and evening and got to go duck hunting for the next four years,” says Dorothy.

As full a life as the Zehnder matriarch has already lived, Dorothy has no plans to fold up her apron, even though she refers to her lifestyle as “retired working.”

“If I want to go home, I do so,” she says. “But not yet.”

Family ties that bind

There are now five generations of Zehnders, counting great-grandchildren, who are part of what Dorothy refers to as a business first family, with son Bill weighing in on the realities that come into play when blood mixes with business.

“It can be the best of all worlds and the worst, all at the same time,” says Bill Zehnder, who has taught business courses related to family enterprises at nearby Saginaw Valley State University.

One of the cautions that he offers students on the topic is the reality that family issues and those involving money need to be clearly delineated, something that his branch of the Zehnder family has tried to keep in mind.

“You’ve got to run it like a business,” said Bill Zehnder.

It’s also clear that the importance of family and business lessons learned have been passed along to younger generations.

One granddaughter, Amy Zehnder Grossi, Bill’s daughter who now serves as general manager of the Bavarian Inn Restaurant, offers an example.

“Grandma and my parents have taught me how to work with other team members,” said Grossi. “Just because they are the owners doesn’t mean they do not work hard. They would never ask team members to do something they themselves would not do.”

Michael Zehnder, another grandson, has also embraced qualities of previous generations.

“One thing I learned from grandma Dorothy and my parents is the importance of seeing projects through to the end. Never give up, because you can always find a solution.”

His mother, Judy Zehnder Keller, remains insistent that those lessons and others continue.

“I tell all team members that our goal is to create enjoyable experiences for our guests,” says Zehnder Keller. “We do that in three ways: First, by coming to work with a good attitude and an expectation that we’ll have fun. Second, we have fun with our coworkers. And finally, we share the fun with our guests. This is part of our family legacy.”

Zehnder Keller also reflects on that legacy with a clearly personal touch.

“Mom is very patient but determined,” she says. “I am amazed how she is able to keep ‘her cool’ working with so many inexperienced young men and women every day. She is continually training and retraining the staff she works with on the importance of ‘no short cuts’ to quality. Throughout the years, anyone who works with her works hard, as they see her work very hard physically. She mentors both young and old with her work ethic. It has been common for team members to say how hard it is to keep up with her.”

As we wrap up the interview, Bill turns to his mother, as the topic of the room where we’re sitting comes up in the conversation and it’s mentioned that the room is where a ceremony marking the 75th anniversary of Pearl Harbor took place on December 7, 2016.

“Do you remember where you were on Dec. 7, 1941?”

Dorothy surely does and recalls the moment. “The radio was right over there,” she says, pointing to a corner not 20 feet from where we’re sitting.

And that moment is at least partially reflective of what Dorothy Zehnder has come to appreciate—beginning with the marriage to her husband, the birth and raising of their children and the nurturing of grandchildren, and, yes, the building of a business that has spread its economic impact throughout the community.

Happy days indeed.