In a world where technology has become increasingly ubiquitous in its penetration to the corporate environment, there remains at least one business line where time seems to have stood still.

It’s the custom and wholesale coffee business, where essentially the same process has remained unchanged for decades.

In fact, for one of those players, an artful blend of tradition, modern manufacturing methods and a steadfast adherence to doing what’s right for the customer is continuing to generate healthy returns a century after it was founded.

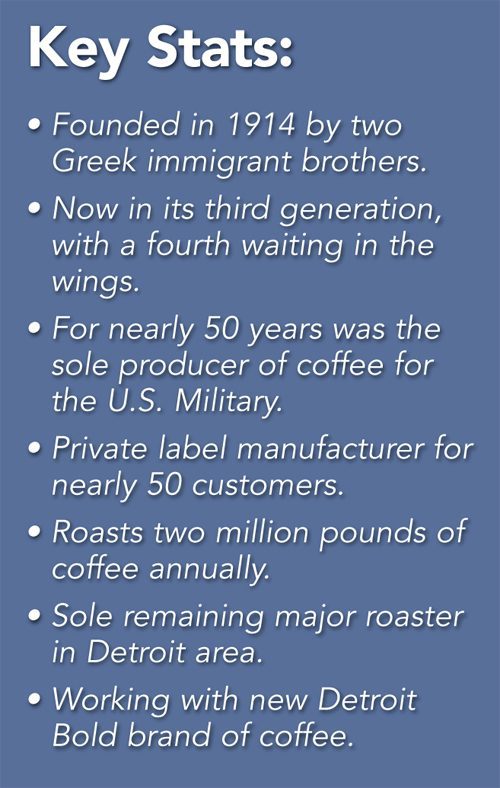

That business is Becharas Brothers Coffee Co., a third-generation passion that has its headquarters, processing and distribution operation in a Highland Park, Mich., facility that was constructed in 1966, just minutes from the original Ford Motor Co. plant that was home to the famed Model T.

Now headed by Nick Becharas as president, brother Dean Jr. as vice president and sister Stephanie Becharas as secretary/treasurer, Becharas Brothers remains steadfast in maintaining processes and systems that represent the essence of the industry.

In doing so, they deal with a product that’s not so much manufactured as nurtured through a series of steps that require consistency and a certain finesse, the end result being a customer who puts their trust in a brand delivering exactly what is expected, day after day, week after week.

We’re talking about taste, of course, as well as a respect and dedication to the olfactory senses that in many ways define a lover of coffee.

But succeeding as Becharas Brothers has since 1914 has taken more than simply honoring tradition. It has taken the perseverance and attention to detail that was modeled by the original brothers, great uncles George and Nicholas, Greek immigrants who first settled in Chicago, with Nick opening a branch plant near where the Fox Theatre is today.

At one point, there would be four Becharas Brothers plants, in Toronto, Houston and Chicago in addition to the Highland Park location.

Today, only Highland Park remains. But size in the coffee business (or at least the number of locations) isn’t the only measure of success. It may not be even the most important.

This is a family business, from its very beginnings to the current third generation of those with the family name and a fourth in the wings who may continue the tradition started by the original brothers.

Fighting on a good cup of coffee

It was one of the founders who sent for a nephew, second generation Dean Becharas, who was father to the current management team and whose idea to set up shop in Detroit lead to a contract to supply canned coffee to the United States military.

That was a relationship that would last for nearly 50 years, ending only when the government opted to “modernize” its supply systems, setting up what is essentially a one-stop shop for all its buying, including coffee.

“The military gave us a five-year ‘heads up’ that they were closing down the old system,” notes Nick Becharas, whose father Dean Sr. died in June of this year.

Becharas Brothers began selling to one of those new vendors for about two years before coming to the conclusion that the new terms were no longer sustainable.

Even though there were other steady customers, including restaurants such as Big Boy (a Becharas Brothers customer for more than 50 years), it was clear that the company would need a new strategy for replacing the volume it was losing from the military business.

Even though there were other steady customers, including restaurants such as Big Boy (a Becharas Brothers customer for more than 50 years), it was clear that the company would need a new strategy for replacing the volume it was losing from the military business.

That’s when Becharas began working on building its private label business, supplying companies throughout the United States with packets of coffee that are sold under as many as 44 separate brands.

Today the private label and corporate sales part of the Becharas Brothers operations account for about 75 percent of the business.

But make no mistake. The people who sell coffee—general food stores and the thousands of coffee shops seemingly found on just about every corner—have lots of choice when it comes to supply.

America’s favorite

The New York-based National Coffee Association (NCA) says “America’s favorite caffeinated beverage” is the second most traded commodity on earth and suppliers abound, maybe not necessarily in the Detroit area like Becharas Brothers but certainly in enough places across the country to make it a very competitive business.

Americans also drink more coffee than in any other single country (the European Union’s 27 countries account for more as a group). Even Brazil “only” accounts for 14.9 percent of the world’s consumption compared with the 18.2 percent of world production that is consumed in the U.S., says www.statista.com.

That doesn’t mean those numbers are staying constant. The NCA says in its National Coffee Trends study published earlier this year that the number of Americans who enjoy a daily cup of the brew has dropped by two percentage points, from 63 percent to 61 percent in 2014.

What did go up, however, is the percentage who prefers the kick of an espresso-based coffee drink like cappuccino or latte. That jumped five points, from 13 percent in 2013 to 18 percent in 2014, findings from a survey of 3,000 adults nationwide show.

Helping establish a local brand

The popularity of the strong stuff may account for the popularity of Detroit Bold, a relatively new customer formerly known as AJ’s CoffeeWorks.

Owner AJ O’Neill, who opened AJ’s Music Café in Ferndale in 2007, became well known a year later when more than 1,000 musicians played their rendition of Danny Boy in a 50-plus hour marathon that was held in honor of O’Neill’s father.

Some have called AJ’s Music Café the “little café that bailed out the automotive industry, one coffee cup at a time.”

While the café closed in 2012, the coffee lives on in the Detroit Bold brand, which O’Neill, who calls himself Chief Bean Officer of the new company, put together with the help of the Becharas team.

O’Neill makes the point that while Seattle’s Starbucks may have put the West Coast city on the map (it also makes the Seattle’s Best brand), Detroit’s coffee heritage—notably through Becharas—is second-to-one.

Roasted in Becharas’ Highland Park building, Detroit Bold and the other variations O’Neill is selling are packaged and then distributed to several stores, including some 127 Meijer and 11 Kroger locations throughout the area.

It’s also available on the Detroit Bold website—www.detroitboldcoffee.com.

O’Neill’s branding effort includes a “giving back” philosophy in that the company offers fundraisers for two of its five types of brew that go directly to supporting integral areas of the Detroit community.

As an example, Detroit Bold’s Solar Blend French Roast supports Highland Park with its sales, portions of which go to benefit Soludarity, a campaign to install 200 streetlights in the city. That campaign began in 2011 after Highland Park lost more than 1,000 of its streetlights due to unpaid electric bills. The campaign hopes to spark some change to bring back the once-vibrant neighborhood.

And O’Neill says companies like his supplier—Becharas Brothers—are guideposts for how he hopes to grow his company, a thinking that flows from Henry Ford’s $5 a day philosophy that not only provided a living wage that was far beyond what workers were earning at the time, but which helped propel into existence what became the American middle class.

“If we’re going to revitalize our community, we must make the community economy viable,” says O’Neill.

But let’s go back to Becharas Brothers, which also has its own brands, including Royal York, named after a Toronto hotel that the current owners’ father Dean Becharas would stay at when the company had an operation in the Canadian city.

Loyal employee base

The Highland Park operation, which was initially built to fulfill the U.S. government contract, has just 25 employees, many of whom end up staying with the company until they retire.

“We just retired a gentleman who worked here for 74 years,” says Nick Becharas. “He started here at 15 and he was ‘retired’ three times. His job was to call on customers, but even when he retired, he still called on them.”

Some of the magic may be how those employees are treated.

“We treat them like part of the family,” says Nick. “They are part of us. We argue like family and we love like family.”

Those aren’t just words.

“It starts with us,” says Nick of his brother Dean Jr. “We aren’t too proud to do anything. And when people who work here see us doing something, they realize that.”

That doesn’t mean that the business doesn’t have its own set of challenges, including dealing with fluctuations in the price of the raw material coffee beans, which can be quite the roller coaster ride.

Becharas Brothers relies on the coffee futures market to manage that risk, hedging against large price moves even while its customers—including Big Boy—are locked into a price for longer than its supplier.

“Price is certainly the most challenging part of the business,” says Nick Becharas. “But we never use price when we do our selling. My Dad always said this: ‘If you get them on price, they’re going to be lost on price.’ We try to sell them on what we’re all about and that’s value. We tell them we’re not going to be the cheapest and we’re not going to be the most expensive. But we service them like no one else.”

That doesn’t mean the company is without its competition. Even in the Detroit area, there a growing number of smaller roasters, including Great Lakes Coffee Roasting Co., founded in 1994 by Greg and Lisa Miracle, and Germack Coffee Roasting Co., which opened in 2012.

And because micro-roasters (able to produce just enough product for a day or two of business) are available, there’s almost no limit to the companies that could set up shop.

But operations the size of Becharas are probably still among the few. It’s here that Nick Becharas says the company’s ethos remains the same, whether the product being sold has the name of a private label customer or the Becharas name itself.

“We treat the private label name like our own name. It doesn’t matter what the market does, up or down, we’re not going to cut corners and our customers know that.”

There are, of course, ways for companies to do just the opposite, which Becharas is happy to explain.

“If you’re blending to a bottom line cost, you can put in a robust coffee then add filler to get down to a certain price. It lessens your blend cost.”

Blending to a profile

At Becharas, that doesn’t happen.

“We blend to a profile, which is based on taste,” says Becharas, whose current business includes distributing coffee to Detroit Bold. Becharas Brothers’ two million pounds of product annually make it one of the largest, if not the largest, institutional roasters in the area. Typically, specialty roasters would produce no more than half that amount in a year.

Having outlasted as many as 15 competitors in the area over the years, Becharas Brothers is proof positive that an adherence to quality and customer relationships rather than simply competing on price alone is an enduring recipe for future success.

“We are big enough that we can slug it out with the big buys,” says Nick Becharas. “We can match prices and give them better product. But we’re small enough that we know every one of our customers and our distributors know them as well.”

Becharas Brothers is a regional distributor, with a geographic range that can be defined as east of the Mississippi. But not too far east. “We try to stay out of the East Coast,” says Nick, referring to a proliferation of roasters that dominate the New England market as making that area just too tough to crack, or at least to do so without a lot of price cutting.

The company buys coffee beans from five countries—Brazil, Colombia, Guatemala, Mexico and Nicaragua—and is supplied through brokers to Becharas, which relieves them of the paperwork required to comply with freight and customs regulations.

The long, long trip taken

But coffee itself has a long way to go from plant to placemat.

First, seeds for the plant are planted in large beds in shaded nurseries. Once they sprout, they are removed and replanted in individual pots, watered frequently and shaded from bright sunlight until they are hearty enough to be permanently planted.

Depending on the variety, it will take as long as four years for the planted coffee trees to begin to bear fruit, cherries that are a bright, deep red when they are ready to harvest. In most countries the picking is done by hand, a labor-intensive and difficult process, although in some places like Brazil, where the land is relatively flat, the process has been mechanized.

Processing the cherries begins as quickly as possible after picking. In areas where water is scarce, freshly picked cherries are spread out on huge surfaces to dry.

In other regions, the pulp is removed and washed away with water, with the remaining cherries separated by size through a series of rotating drums.

They are then subjected to water-filled fermentation tanks, typically for anywhere up to 48 hours, followed by rinsing and drying to about 11 percent moisture.

Coffee beans are then milled, polished, graded and sorted, by both machine and hand, all before exporting.

It’s once the coffee is received by companies such as Becharas Brothers that the product is roasted and processed into the bags that head to the final retailer, a coffee shop or retail store.

Even in an industry where the economic factors, weather and global competition come into play, Becharas Brothers appears to be on solid ground. It’s a business that not only has a heritage behind it and a steady customer base, but its owners have already proven the ability to re-invent themselves, from the major customer years of its contract with the U.S. military, to its current position as supplier to at least 44 private brand labels.

And with another generation in the wings—the fourth in the Becharas family line—and connections with brands like AJ O’Neill’s Detroit Bold, the company is well-poised to continue as a driving force in the business.