Feeding more people efficiently and sustainably through urban agriculture is a good idea, but you need more farmers and more for-profit entrepreneurs engaged. That is the message from Will Allen, who runs, by many accounts, the largest urban agriculture operation in the world.

“Urban agriculture right now is still very small scale in terms of the amount of food we are producing, the good food, the food we want to eat,” says Allen, who quotes a recent survey that 86 percent of people prefer locally grown food.

“People are aware of issues with food … and prefer to know where it comes from,” he adds.

Allen, whose organization GrowingPower.org is based in Milwaukee, Chicago and Madison,Wis., was one of several local-food movement luminaries participating in a panel at “Greening the City: The politics and possibilities of greenspace,” an event organized by Culture Lab Detroit and held last fall at the College for Creative Studies.

The evening featured Allen, Food to School star Alice Waters, and Patrick Blanc, the French inventor of the vertical garden. The panel was moderated by Stephen Henderson from the Detroit Free Press.

Allen, a 2008 MacArthur Fellow (sometimes referred to as a “Genius Grant,” although the term is discouraged by the MacArthur Foundation), has been involved in urban agriculture for 22 years and wrote the book “The Good Food Revolution.” He said his family has been continuously involved in farming for 400 years.

Growing food near you or your community is valued on many levels, especially considering that more than half the world’s population lives in cites. In the United States, the figure is 80 percent, according to a 2010 report by the U.S. National Academies. In another report, the average distance to bring food to a major retailer in America was cited at 1,500 miles. Urban and peri-urban agriculture can be defined as the growing of plants and the raising of animals within and around cities.

“It makes sense, because that was the way it was. It used to be urban farms,” Allen said on the panel. “People always grew food close to where they lived, but we have gotten away from there. Now we are trying to get back to that, but there are so many issues, such as land policies cities have set up that are anti-farming.”

But discouraging land use policies are changing. Allen cited Milwaukee as “probably the best example in the country,” where farming and composting is allowed in every zoning district. In 2013, Detroit adopted its first urban agriculture zoning ordinance, legislation that defines farm stands, farmers’ markets, greenhouses, aquaculture, greenhouses, hoop houses, urban farms, orchards and gardens.

But discouraging land use policies are changing. Allen cited Milwaukee as “probably the best example in the country,” where farming and composting is allowed in every zoning district. In 2013, Detroit adopted its first urban agriculture zoning ordinance, legislation that defines farm stands, farmers’ markets, greenhouses, aquaculture, greenhouses, hoop houses, urban farms, orchards and gardens.

“It’s about food and social justice,” Allen continued, responding to a question about the broad impact of urban agriculture. “I believe food is a way of making sure people’s lives and communities improve, changing the food system and creating jobs so that people can have good food. It’s a shame that in America three out of 10 young people go to bed without a meal. We should all be ashamed of that and try to fix it.”

On an even broader scale, an estimated 800 million people worldwide practice urban agriculture, according to a report from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Another report, this one from the Worldwatch Institute (worldwatch.org), cited that 15-20 percent of the world’s food is grown in and around urban areas. Both of these references were mentioned in a 2014 article by Elizabeth Royte on ensia.com.

From Allen’s view, the “fix” to the food system and its impact on social justice will come from more startup businesses involved in urban agriculture, as well as adding more farmers to the mix.

“I believe it is going to come from entrepreneurs. Non-profits are good for training and educating and to show people that it can be done. We have 4,800 farmers’ markets in the U.S. We have to bring the good organic food into the retail grocery stores. We have to get money in the next farm bill to train farmers on the sustainable side of this.”

Detroit and Michigan

While Detroit may be known as the Motor City, it is now gaining a name as the Urban Ag city. Within city limits alone, there are nearly 1,400 community gardens – and some say the number is closer to 2,000 – pumping out fresh produce for neighborhoods, schools and other organizations. Add to that the commercial market gardens, with growing schedules and processes geared to getting food to markets, restaurants and retail outlets, not to mention family gardens.

In 2014, that mix of growers produced more than 400,000 pounds of produce in Detroit, enough to feed 600 people, according to Royte’s article in ensia.com. And in 2015, that production increased. The Detroit-based Garden Resource Program reported a production of 550,000 pounds of fresh produce from its 1,375 member gardens. The organization added 540 new gardens to the mix this year, which includes 424 community gardens, 90 market gardens, 805 family gardens, and 56 school gardens, with some 15,600 residents involved in tending to those gardens. Other reports estimate the involvement at nearly 20,000 Detroiters.

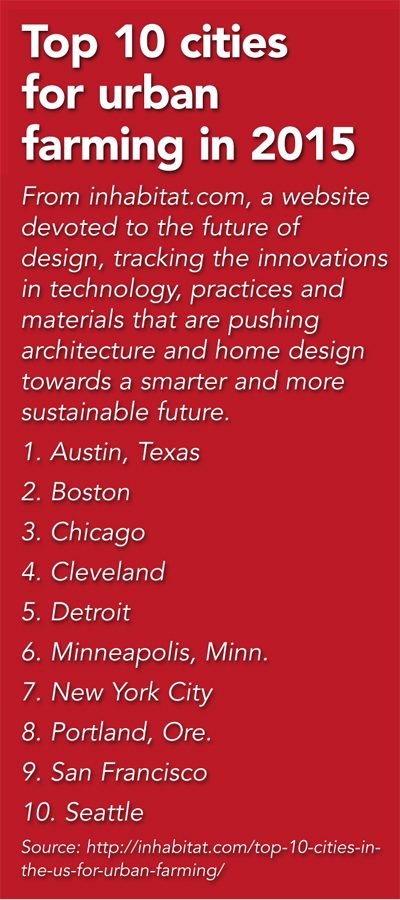

Those numbers have put Detroit among the top 10 cities for urban agriculture. In a study from seedstock.com, Detroit topped a list of 10 cities that are leading with innovative urban agriculture ordinances, rules that point the way for “a new economic future grounded in sustainable food production in urban centers.” Detroit’s urban farming ordinance and abundance of vacant lots contributed to that distinction.

In another study, this one reported on inhabit.com, a design, innovation and environment website, Detroit ranked fifth in a list of top 10 cities for urban agriculture. The report listed the community garden sties at 1,350, pictured retailer Detroit Farm and Garden, and cited the Hantz Woodland project to build an urban farm on 1,500 parcels it bought.

The Garden Resource Program is part of Keep Growing Detroit (KGD), a non-profit organization “dedicated to cultivating a food sovereign Detroit … where food and agriculture are a driving force in resident-led community and economic development,” according to their report.

Their membership had 200 acres under cultivation in 2015. The organization is involved in education and training through numerous agriculture and gardening-related workshops, production and distribution of plants and seedlings throughout the season and much more.

This summer’s 18th Annual Tour of Detroit Urban Gardens and Farms had more than 400 visitors touring 36 gardens and farms. In another example, Keep Growing Detroit worked with the Fair Food Network to develop a training program that resulted in 22 Detroiters receiving on-the-job training in hoop house construction (unheated greenhouses) while helping five growers in the construction process.

Another part of Keep Growing Detroit is the market sales collective, Grown in Detroit. In 2015, 45 gardens and farms from across the city earned nearly $50,000 at 54 markets.

The non-profit organization Greening of Detroit has a mission of sustainable growth of a healthy urban community through trees, green spaces, food, education, training and job opportunities. Among their many activities are their 2.5-acre Detroit Market Garden, urban agriculture apprenticeship and internship programs, soil improvement, and work with school gardens and parks. They have planted 85,000 trees in Detroit since 1989. Their other farm gardens in Detroit include Lafayette Greens downtown and Romanowski Farm in southwest Detroit.

For these organizations, the city’s open spaces are an opportunity. In 2014, KGD helped Oakland Avenue Community Garden and Neighbors Building Brightmore build their heated greenhouses, one each, which increased their capacity to grow more transplants. Ashley Atkinson is a co-director at Keep Growing Detroit.

“We would like to see the city embrace the notion that 5,000 of its existing 13,000 vacant acres be available for appropriately scaled agriculture,” she said.

A Michigan State University study recently concluded the city could grow 75 percent of its vegetable needs and nearly half its fruit consumption on less than half the available vacant land.

Atkinson, who has been involved in local agriculture and community garden initiatives since 2000, beginning in Flint (where she started the Flint Urban Gardening and Land Use Corp.), is among many in the movement that say urban agricultural statistics tell only part of the story. Being involved in gardening and growing has social and health benefits.

“Some of the major findings are that it definitely has a large health impact, many people report having a reduction in weight, (lower) blood pressure, being able to reduce medications or come off medicines completely, along with an increase in physical activity,” she said. “There are significant savings (compared with buying produce retail), and a lot more access to fresh healthy food. People talk about the connection to nature and feeling connected to other gardeners.”

Economic scale

Indeed, any measure of the economic impact of urban agriculture must go beyond the numbers, explained Michael Hamm, professor of Sustainable Agriculture at MSU.

“There is not an easy way to look at economic value,” said Hamm. “It is not as high as what many people would like to see. It’s not a magic bullet. It will create some jobs (but) it is not like the auto industry opening a factory. It is important in urban agriculture that you talk about the multiplicity of benefits, not just any one, because any one by itself doesn’t stack up in comparative analysis – as the highest and best use for land.”

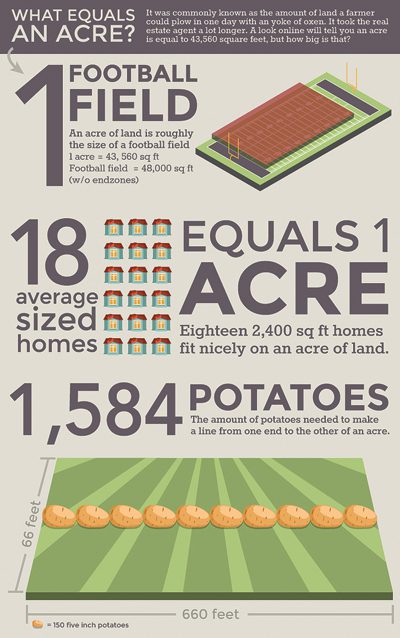

Hamm offered an example in the city of a reasonable use of a half-acre, using about 20,000-21,000 square feet. With about 9,000 square feet of high tunnels (unheated greenhouses or hoop houses), and the rest grown outdoors, the endeavor may provide hourly wages for a few people and a living income for a small family – if market conditions are right.

“Economic impact is dependent on what markets they sell into and what are the price points for those markets,” he said. “Like any business – profits depend on expenses relative to sales.”

While a factory on that land would produce more money and employ more people, Hamm said there are other factors to consider, including the greenspace a farm provides for the community as well as ecosystem services, rain absorption, less sewer system uses for water dispersal, and higher real estate value.

“There are four or five avenues that urban farms provide value into a city that other uses do not,” he said.

Statistics on urban agricultutre, statewide and nationally, may be difficult to assess. But this is partly because of the different definitions involved and the fact that no single national organization brings it all together, Atkinson explained.

Statistics on urban agricultutre, statewide and nationally, may be difficult to assess. But this is partly because of the different definitions involved and the fact that no single national organization brings it all together, Atkinson explained.

While a number of organizations may be identified as “community gardening” organizations, that category is further segmented into allotment plot organizations and communally operated organizations. Then there are urban farming organizations that tend not to identify as community gardens. There are also for-profit models and not-for-profit models, adding to the differentiation.

However, one study defines the impact of “local agriculture” in Michigan, basing its numbers on recorded transactions across farms and processors to retail, food service and to consumers. The study, conducted by the Center for Economic Analysis and the Center for Regional Food Systems at MSU, defined local food as “fresh and processed food that originates from Michigan farms, and is processed and ultimately consumed within the state.”

As recently as 2011, the study said, farms in Michigan produced $9 billion in commodities, $5 billion of which was exported. Of the remainder, about $2.5 billion went to processors.

Also from the study: Michigan’s local food system supported 18,627 jobs along the agri-food value chain, with unprocessed foods making up the largest share. The system resulted in $680 million in wages and income for growers, representing about 17.7 percent of Michigan’s total food consumption sales.

For-profit in Detroit

Brother Nature LLC, located in Detroit’s North Corktown neighborhood, is one of the for-profit farms in the city. Just a few of the for-profit operations on a growing list include Rising Pheasant Farm, Food Field, Hantz Woodlands, Fresh-Cut Flower Farm, Buffalo Street Farm LLC and Labrosse Farm.

For Brother Nature, owned by husband and wife Greg Willerer and Olivia Hubert, viability has come from a tenacious mix of available land, community supported agriculture (CSA) and hard work. They cultivate on 10 lots, two of which they own. Their bread and butter is a salad mix made from a variety of field greens along with pea tips, and then seasonally extended with hoop house plantings such as spinach.

For Brother Nature, owned by husband and wife Greg Willerer and Olivia Hubert, viability has come from a tenacious mix of available land, community supported agriculture (CSA) and hard work. They cultivate on 10 lots, two of which they own. Their bread and butter is a salad mix made from a variety of field greens along with pea tips, and then seasonally extended with hoop house plantings such as spinach.

Willerer, a former middle school teacher in language arts, started selling in the summers in 2005 and then went full-time as a grower in 2009. Hubert studied horticulture at MSU and in England. Along with 14 CSA members, an intern in previous years, a couple of hired assistants, their dog, Watson, and toddler, Wren, they get it done. Seasonal snowplowing work also helps with the overall budget.

With CSAs, members invest in the farm, work a designated number of hours and go home with produce every week or another periodic distribution.

“Most small organic farms don’t exclusively do one thing,” said Willerer. “Some do, but most have at least three ways that they market and sell their produce. CSA is the easiest.”

There’s also a somewhat flexible rate for those wanting to rent the land, although $500 seems to be the going rate for participation in a CSA operation, said Willerer.

“But that’s hard to find in an economically stressed city like Detroit – so we let people put down $100 if they want to join and we go longer than other CSAs, about 25 weeks. Now we have about 14, down from 20 when we first started.”

Most of their sales are at Detroit’s Eastern Market, Wayne State Market, and also in Corktown Market, which opened in the summer of 2015. They also sell wholesale to a handful of restaurants, a third way to move produce.

Each week, they produce between 125 pounds and 175 pounds, earning them an income in the mid-$30,000 range. “We are still peasants,” Willerer said.

Considering Detroit’s top-10 national reputation in urban agriculture, Willerer sees future growth if the city takes the right steps.

“The city needs to basically get out of the way, embrace it and foster it in certain areas,” Willerer said. “They will find that more people who want to live differently – without the suburban lifestyle – will stay in the city and other people will come to the city.”

He also noted the security and stability urban farms bring to a neighborhood.

“There’s the safety factor,” Willerer said. “We confront people regularly. In terms of keeping the block and surrounding homes safer, if we are out there working, doing stuff around the farm; that’s at least two sets of eyes, plus Watson [their dog] being vigilant, checking things out, and that helps everyone and adds value to the neighborhood.”

While Willerer may be optimistic, MSU’s Hamm is guarded when it comes to the viability and impact of urban agriculture, making the point that core cities, where the city council has sway, were never meant to be the dominant provider of food for the people who live there. Period.

But that doesn’t mean that there should not be community gardens and the greenspace they create, the fruits and vegetables they create, and beekeeping and the great benefits it provides, he said. “And it also doesn’t mean that there shouldn’t be the gathering places – in New York City, Boston, DC, wherever – and the huge amount of social capital built around those places.”

It also depends on the city.

Scores of cities in U.S. are losing population in their core cities, Hamm said, citing Detroit, Flint, Milwaukee, Cleveland, Toledo and his own native St. Louis, Mo., as places where “out migration” usually means vacant lots, abandoned buildings, with the usual solution being to tear them down and mitigate the negative activities that can occur.

“But in Detroit, and other places, you can think more robustly about what to do with that space. You want to preserve some room for development, because you want some infill occurring,” Hamm said. “The loss of population will never return to what it was (in Detroit) so you have the opportunity to add large amounts of greenspace, and that includes opportunities – where you want greenspace, and where you want to rebuild density. It (also) means greater amenities for people who want to live there, to recreate, to walk and enjoy.”

What’s true is the potential to improve fruit and vegetable access, especially for the people of Detroit, Hamm said, adding that he thinks it will be a long time before there will be either the political will or the capacity to grow a large percentage of the fruits and vegetables for the residents of Detroit.

“I think that in a place like Detroit, urban agriculture will be a part of the mix of what happens in the city on a robust basis, where you can see it wherever you go in the city. And, realistically, that is probably what is going to happen.”

The importance of new entrepreneurs

Hamm, Willerer and Allen all underlined the need to establish viable for-profit models for urban agriculture, in addition to successful non-profits. Allen, whose Growing Power organization farms 300 acres and 25 acres of greenhouses, said there is a need for more farmers.

“That’s the biggest problem,” he said. It’s going to be the entrepreneurs who buy up four or five lots and begin to learn to farm. This change you are trying to do in Detroit will take time (and) it will take patience. A great place to cut your teeth in farming is in cities where land is available almost for nothing.”

Hamm said new farmers need to see examples of viable, for profit businesses so that they can see a pathway for them to make a living, and one that is not dependent on foundations.

“The challenge is to have examples of truly for-profit, private businesses that are doing it. That is what we need. They are out there.”

While he praised the intentions and outcomes of not-for-profit urban agriculture, Willerer, between bites of Thai-spiced noodles with fresh cilantro and tending to his daughter, Wren, said those organizations spend a lot of time with accountability and the business of running a not-for-profit.

“The boots on the ground effect and what actually gets done is negligible sometimes. When it’s your own money, you are going to work 80 hours a week at it.”

Willerer also agrees, to a point, with Will Allen’s view that the impact of having more entrepreneurs involved may help reduce the number of people who are dependent on someone else for their livelihood.

“To me, I wouldn’t say more corporations, but more mom and pop type businesses that have a consciousness about them can create a lot of change.”