Michigan’s new Department of Talent and Economic Development (TED) is one of Gov. Rick Snyder’s latest reorganization initiatives to streamline state programs. Aside from just being a great state agency acronym, TED is the key to developing the governor’s skilled trades economic strategy: to make Michigan a talent resource leader – the place technology, manufacturing, and robotics companies want to locate, because the skilled trades talent they need is here.

Streamlining the soup

Currently, Michigan has an array of business, community, and talent development programs that each work independently of the others. To deliver, in the governor’s words, a “comprehensive, unified approach” to talent development, TED’s first objective is to streamline these programs, so they are collaborating and working toward common goals.

To that end, the Michigan Strategic Fund (MSF) and the Michigan State Housing Development Authority (MSHDA) are being transferred to TED’s umbrella. The MSF is a board of directors responsible for steering Michigan’s economic growth and job development, and MSHDA is the state’s primary community development agency. The State Land Bank Fast Track Authority will transfer from the executive director of MSHDA to that of TED. Also under TED’s umbrella is the new Talent and Investment Agency (TIA) (created under the same executive order as TED).

TIA’s role in this restructuring and the larger skilled trades economic strategy cannot be over stated. It will be responsible for all state talent development efforts. To that end, the Workforce Development Agency (WDA), the Governor’s Talent Investment Board, and the Unemployment Insurance Agency are transferring to TIA. It will also coordinate talent programs not directly under its authority, including those at the Department of Military and Veterans Affairs, the Michigan Department of Human Services, and others. (The Office of New Americans, just created in 2014, will transfer out of the executive office, but not to TIA. Instead it will transfer to the Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs (LARA)). Stephanie Comai will leave her post as deputy director of LARA to become TIA’s director.

Heading up this alphabet soup is the Michigan Economic Development Corp., the face of Michigan’s business development efforts, with activities ranging from attracting businesses and talent to promoting tourism. The MEDC falls under the auspices of the department of Talent and Economic Development and is connected via the Michigan Strategic Fund. Steve Arwood oversees the TED department and is CEO of the MEDC. Arwood was recently promoted from chief operating officer to CEO at the MEDC.

As representatives of the business, talent, and community development domains, respectively, Arwood, Comai, and Wayne Workman, interim director of MSHDA, have some tough work ahead of them. They will have to weed out duplication of efforts while increasing collaboration between entities that, historically, have worked independently of each other. They will have to design new ways to measure their impact as part of TED while maintaining their own identity, mission, and goals. As the director of a new department within a new department, Comai’s job may be the most complex.

Despite the challenges, none of the three appears daunted. All seem to understand that this collaboration is a natural fit and long overdue.

A customer driven focus

If all goes according to plan, each domain will leverage their new, collective power to make a greater impact on their customers (citizens, workers, businesses, communities, tourists) than each could do independently. The entry points to services will remain the same, but the resources that can be brought to bear on the customer’s needs will increase: An unemployment insurance recipient may be linked with the WDA for re-training; a community hoping to expand may be paired with a business in need of a location.

As an extension of this customer-driven focus, Arwood hopes that TED can utilize its leverage to make federal dollars more “flexible.” Federal grants help pay for the state’s talent, community, and business development programs, but each grant has its own regulations. In his State of the State address, the governor announced that his administration would seek waivers allowing the state to consolidate these programs in an effort to lower service barriers. Changing the federal government may be an uphill battle, but Arwood believes TED will provide a unique perspective—the unified voice of Michigan’s business, talent, and community development sectors.

TED’s mission: Make Michigan #1 in the skilled trades

TED’s mandate to streamline and collaborate underpins a broader strategy of the Snyder administration, one that the governor highlighted in his State of the State address: “to make Michigan number one in the skilled trades in the United States.”

While the definition varies slightly from source to source, Arwood defined the skilled trades as any work that utilizes technology. The skilled trades are “not industry specific,” said Arwood. They could include manufacturing, data, medical, industrial, construction, agriculture and forestry, and other fields. To understand the breadth of the skilled trades, it’s useful to think of the machines needed to build the parts that go into the machines that will help deliver the final product or service. Every step on the path from product inception to production and delivery represents a potential worker. Potential because the jobs must be available and attainable.

While the definition varies slightly from source to source, Arwood defined the skilled trades as any work that utilizes technology. The skilled trades are “not industry specific,” said Arwood. They could include manufacturing, data, medical, industrial, construction, agriculture and forestry, and other fields. To understand the breadth of the skilled trades, it’s useful to think of the machines needed to build the parts that go into the machines that will help deliver the final product or service. Every step on the path from product inception to production and delivery represents a potential worker. Potential because the jobs must be available and attainable.

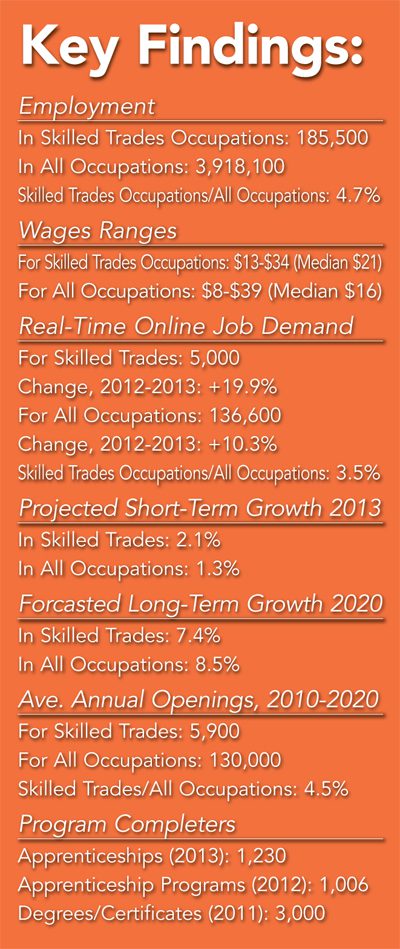

Two reports from Michigan’s Department of Technology, Management, and Budget (DTMB) indicate that the skilled trades meet both of those criteria. In its 2013 report on skilled trades employment, the DTMB reported that the skilled trades is one of the top in-demand fields and that job growth in this sector will continue through 2020. This same report found that skilled trade wages range from $13 per hour for workers with entry-level experience to $34 per hour for experienced workers, wages that on average are higher than those for all other occupations combined.

In its December 2014 report on online job demand, the DTMB found that the combined fields of construction and repair, production transportation, and farming, fishing, and forestry had 16,650 job openings, second only to professional fields, such as financial operations and legal, which came in at 18,150 job openings. Unlike professional fields that might require a four-year degree (or more), skilled trades jobs require mid-level skills that can be learned on the job, at a two-year community college, or through a technical training program.

While these reports favor the governor’s plan and TED’s mission, there remains much debate about whether or not there truly is a need for more skilled trades workers, and, even if there is, whether or not the skilled trades are really the way forward for Michigan.

The shortage debate

An MIT study published in 2014 found that, nationally, employers have been able to fill their skilled trades vacancies, and training was not a barrier to employment. The study suggested that the real issue may be a lack of demand, or job openings, for skilled trades workers. Writing for the Economic Policy Institute, Heidi Shierholz cited the 2013 Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey as evidence that the supply of unemployed workers far outnumbers employer demand for them. Sharon Miller, vice chancellor of external affairs for Oakland Community College (OCC), says the national data may be a reflection of the nationwide average but not of Michigan’s unique situation. The DTMB’s 2013 skilled trades report found that the demand for skilled trades workers was strong but that supply may be weak.

Evidence of a weak labor supply pipeline is certainly apparent in the experience of DENSO Manufacturing Michigan, in Battle Creek, and Merrill Technologies Group, headquartered in Saginaw. DMMI’s corporate services manager, Sarah Frink, commented that hiring enough workers to keep pace with the company’s growth is challenging because companies are competing for the same pool of skilled trades workers. Miller echoed that concern, saying companies “can’t keep shuffling workers.” At DENSO, the struggle to fill jobs is further complicated by the number of experienced skilled trades workers who are retiring,

Back in 2000, Jason North, Merrill Technologies Group’s hiring manager, had an “easy” time finding skilled labor. However, over the course of the next few years, the landscape changed. The few applicants who had the proper qualifications on paper could not pass Merrill’s welding test. North, now manager of operations, said he wasn’t the only one noticing the supply problem back then. His customers, one as far away as California, echoed the same frustration. Today, North says, the company is still facing a skilled trades shortage.

Despite stories like these, those experts who contend a labor shortage does not exist point to stagnant wages as evidence of lack of labor demand. Lou Glazer, president of Michigan Future Inc., notes that a worker shortage should spur employers to increase wages, but it has not. However, OCC’s Miller points out that companies do not raise wages or enhance job benefits when unemployment rates are high, and Michigan’s rate, although improving, remains above the national average. (According to the DTMB, although now at about 6 percent, Michigan’s unemployment rate, as late as 2013, still sat between 8 and 10 percent). The hope, she says, is that as the economy improves more employers will begin investing in their own training and job marketing.

Certainly that was the situation for Merrill’s welding school, the Merrill Institute. Located inside the company’s fabricator site in Alma, Mich., the school was the brainchild of North. After years as a hiring manager where he experienced, first-hand, the lack of available skilled trades talent, he approached the company’s leadership about launching an in-house training program. Unfortunately, that was about the same time that the Great Recession hit. Although the leadership supported the idea, it was not the time to make the financial investment, so the idea was put on hold until 2011 when the school launched its first class.

Today, North said, the school has graduated about 190 students and has an 89 percent employment rate after graduation. Although designed as a feeder school for Merrill Technologies, only about 35 of the graduates have gone to work for Merrill. The remainder of the 89 percent went on to work for

other companies across the country. That feature of the Merrill education is critical, said North, because, unlike welding programs elsewhere, Merrill Institute graduates walk away with an American Welding Society certification, a national credential, which allows them to take jobs anywhere in the country.

At DMMI, Frink touted their in-house apprenticeship and skilled trades mentorship programs, which are designed to train existing skilled trades workers (from fields like construction and manufacturing) on DENSO systems while earning their professional certification. Frink cited an “attractive” benefits package as well.

Whether or not it can be accurately defined as a shortage, Michigan’s labor data, skilled trades businesses, and training agencies are sending the same message: There is demand, but the supply of labor is dwindling. For TED, the question to be answered is how to get workers back in the pipeline?

Overcoming hurdles

TIA’s new director, Stephanie Comai, said that the skilled trades pipeline will be a focal point for her department, citing the need to improve marketing of skilled trades opportunities and to start the “conversation [about a career in the skilled trades]…earlier than high school graduation.”

As Comai already knows, that marketing campaign will have to address the skilled trades history. In the past, the work was thought of as dirty, greasy, and requiring more brawn than brain. Today, though, manufacturing plants are clean, and the jobs inside them require some level of post-secondary math and technology skills. That education requirement may bring added (and overdue) respect to this work, but it may also make the jobs less attractive. Lou Glazer noted that, not long ago, with nothing more than a high school education, a line worker could earn a high wage. Today, workers need more education, but they will be paid less—at least initially. And in a global economy, competition with overseas companies keeps downward pressure on wages and makes the fear of outsourcing a permanent fixture on the landscape.

Comai, like many others, contends that skilled trades wages are “good.” She highlights the same DTMB report quoted above that shows average wages between $13 and $34/hour. However, Glazer questions whether those averages are good enough to attract workers. As with everything, whether or not a wage is good depends on context. Even if $13/hour is high compared with other fields, is it a wage on which a worker can support his/her family over time?

Because there are fewer higher level positions than there are entry level positions, many workers will only make a starting wage. Figuring out that starting wage is challenging because the skilled trades cover a wide range of jobs across an array of industries. In addition, Jason North noted that there are other variables, including union membership, the density of other industry in the area, job context (for instance, outside on a pipeline or inside a plant) and, of course, demand. He knew of a company in Texas taking in welding new-hires at $28/hour and one in Warren, Mich., with a starting pay of $18/hour, but, in central Michigan, starting wages could be as low as $12 or $13/hour.

Behind the scenes, TED will have to hammer out critical relationships between business, government, and education. DENSO’s Sarah Frink stated that TED’s promise is in “helping us build better collaboration between industry, education, and the state.” Some of this groundwork has already been laid through programs like the Regional Prosperity Initiative, the Skilled Trades Training Fund, which links workforce development agencies with businesses and, potentially, educational institutions to train new or existing workers, and the New Jobs Training Program, which links businesses with community colleges who provide training to their workers. (DENSO has been a recipient of the fund and the program.) Yet, if Merrill Technologies Group’s experience is any guide, there is much work to be done.

Merrill has had mixed experiences with government. According to North, Michigan Works Gratiot/Isabella is an “excellent” partner, and the STTF along with Workforce Investment Act funds have been great sources of support to train students. Unfortunately, North has not been able to reproduce that positive experience with other local government entities because of the view held by some that welding is not an “in demand job.” On the education front, North’s past interactions with some community colleges suggest they lack an interest in skilled trades business partnerships or in welding generally.

With so many different stakeholders, academics, trainers, business leaders, state workers, and job seekers, can TED really make a difference?

Karol Friedman, director of talent development for Automation Alley, hopes so. In her view, TED is a “brilliant move” by Snyder because it shines a statewide spotlight on the critical relationship between talent development and the state’s economic progress. OCC’s Miller said the same: The “number one issue in economic development is a talented workforce.”