Someone looking for a story that will bring a smile to his or her face won’t get much satisfaction if the subject happens to be no-fault auto insurance in the state of Michigan.

Certainly part of the tale relates to how much Detroit drivers (or at least the estimated half who actually buy the no-fault insurance state law requires) pay for their policy (hint: it’s a lot more than that paid by those who live elsewhere).

But the issue goes beyond the raging debate over the benefits and risks of D-Insurance, a plan proposed by Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan, himself a former hospital executive who may know more than the average politician about the effect medical bills resulting from car crashes can have on the system.

To fully understand why Duggan and Detroit City Council want D-Insurance to be approved by the state as an option (not a requirement), some definitions are required, starting with what no-fault insurance is and what it means to the system it supports.

No-fault means what you’d likely guess it means: that regardless of who may have caused the auto accident, the insurance companies involved pay the damages of their policy holders. Essentially, the system says: “we don’t care who’s at fault.”

No-fault means what you’d likely guess it means: that regardless of who may have caused the auto accident, the insurance companies involved pay the damages of their policy holders. Essentially, the system says: “we don’t care who’s at fault.”

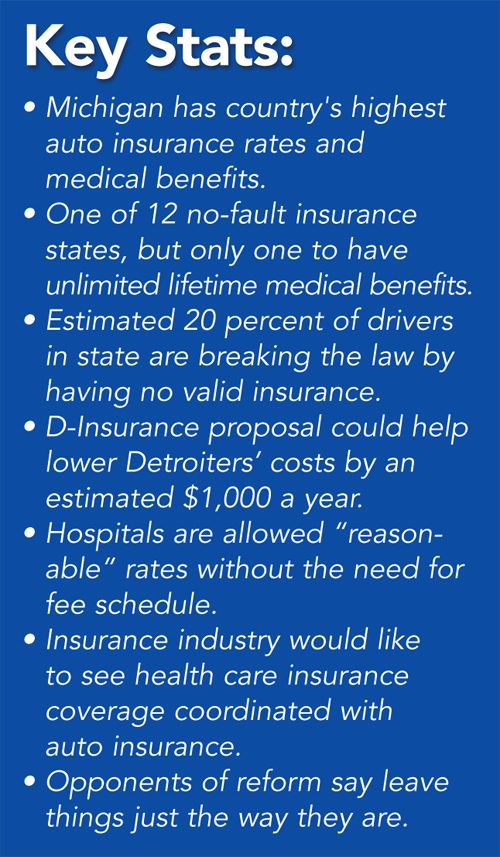

Where things start to get complicated is that some drivers are breaking the law by failing to have a valid insurance policy. And by “some” we’re talking about quite a few—an estimated 21.5 percent throughout the state and possibly half of those living in Detroit (a figure Duggan has used in his presentations).

Yes, it’s a law that has immediate consequences if you’re caught. It’s a misdemeanor conviction and you’ll pay a fine of up to $500 and possibly go to jail for a year.

But the systemic consequences of the status quo may be even greater.

Hospitals, of course, are legally required to provide care following an auto accident, even though the driver who is not insured is, at least in theory, on the hook for the cost.

But while the driver may be “driving dirty”—the industry term for the practice—any passengers in his or her vehicle are protected, as well as drivers and passengers in other vehicles involved in the accident.

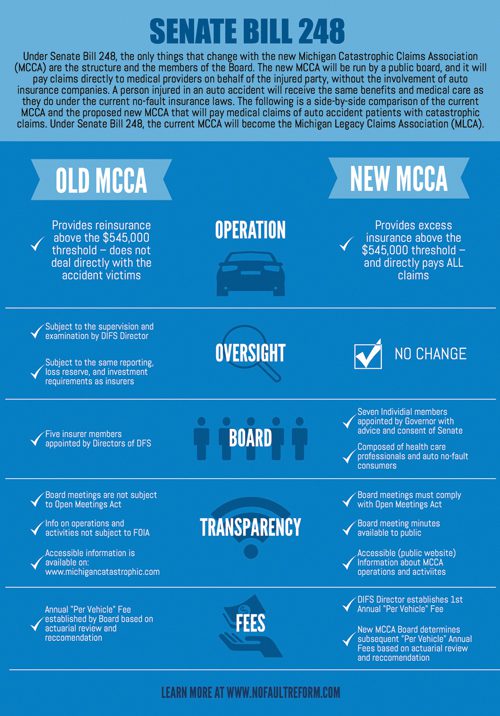

Under Michigan’s system, insurance companies pay the hospital bills and are reimbursed for any costs that reach more than $545,000 (the limit is adjusted every year for inflation). Those reimbursements are made by the Michigan Catastrophic Claims Association, a private non-profit unincorporated association that was created by the state in 1978 and which gets its funding from insurance policies at a rate currently set at $150 per vehicle.

Limits and D-Insurance

Where things start to get a little ugly is when you look at what the limits to medical coverage—the personal injury protection (PIP)—are in Michigan and elsewhere.

For Michigan, it’s an easy answer: there are no limits. Ever.

For Michigan, it’s an easy answer: there are no limits. Ever.

The second highest state, the highest where there are any limits for PIP coverage, is New Jersey, which caps its coverage at $250,000.

What isn’t being talked about much is the idea that drivers who have health care coverage, either through their work policies or some other form of coverage (perhaps Obamacare, as a veteran or Medicaid), are effectively paying for duplicate coverage, since their coverage for everything but a car accident doesn’t kick in until the auto insurance coverage limit is reached.

Which for Michigan is never.

Duggan’s D-Insurance proposal, which has been approved by the Michigan Senate but not the State House, has its genesis in a report by Pinnacle Actuarial Resources, commissioned by the city to determine the best way to fulfill one of Duggan’s campaign promises—action on the perceived disparity in insurance rates for Detroit residents.

“(Pinnacle) said if you don’t fundamentally change the state law, nothing will be done,” Duggan told Detroit City Council when he formally introduced the concept last May.

D-Insurance would, if approved, provide Detroit residents (and those in other cities where the percentage of uninsured drivers is at least 50 percent) an option to buy coverage with a limit that matches New Jersey at $250,000.

Duggan, quoting Pinnacle’s report, said a full 44 percent of insurance premiums accounts for the PIP coverage, with one third of Detroiters only buying PIP. “That amounts to 88 percent of what they’re buying today,” he said in May. “They’re getting killed on the medical insurance (portion).”

Duggan, who ran the Detroit Medical Center from 2004 until it was sold to Vanguard Health Systems in 2010, presumably knows something about what the D-Insurance $250,000 cap would mean in practical terms.

“An ER and hospital stay that goes over $250,000 is very rare,” he told Detroit City Council, adding that only an estimated 1 in 10,000 drivers would have a hospital bill that went higher.

Again, under a new system, health care insurance would kick in beyond that amount.

The D-Insurance option would provide up to $25,000 in coverage for care after a hospital stay, a limit that is still higher than 45 other states.

The D-Insurance option would provide up to $25,000 in coverage for care after a hospital stay, a limit that is still higher than 45 other states.

If approved, Detroit would go out for competitive bid on the D-Insurance option, with Detroit City Council ultimately deciding which company it would use as a provider.

In Michigan, the top three insurers—State Farm, AAA, and Auto-Owners—account for about 45 percent of the market.

The costs of care

One of those, AAA, highlighted its concerns over what it called the “runaway costs” associated with the state’s mandatory unlimited medical coverage.

In the November/December 2015 issue of AAA Living magazine, the insurer pointed out that drivers “bear a greater portion of the cost burden as they must pay more for uninsured-motorist and mandatory-medical coverages.” AAA said the issue has become a “vicious cycle, one that will likely continue until the affordability of auto insurance—and more specifically medical coverage in auto accidents—is addressed through effective legislative reform.”

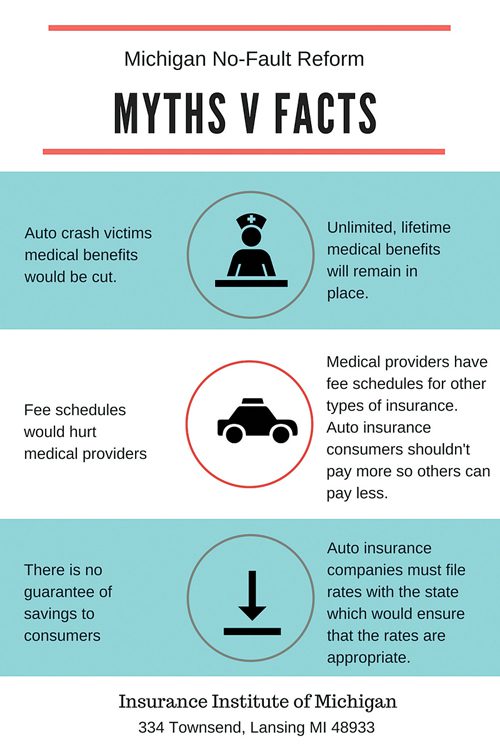

Michigan auto insurers (through their industry lobbying organization, the Insurance Institute of Michigan) argue that one of the key issues that affects insurance rates is not so much the lack of a cap, but the unwillingness of health care providers to deal with the costs of the care.

“Unlike most health care legislation, there’s no built-in cost containment with auto insurance in Michigan,” says Peter A. Kuhnmuench, executive director of the IIM, based in Lansing. “It’s almost the opposite. The term ‘all reasonable care’ generically mandates anything that they need as far as care is concerned.”

Kuhnmuench likens what hospitals charge insurance companies under Michigan’s law to “suggested retail on steroids.”

In an editorial written to support changes to the legislation, Kuhnmuench compares Michigan rates (averaging $1,171 according to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners) with Ohio ($713), Indiana ($723), Illinois ($805) and Wisconsin ($666).

“Michigan hospitals have methodically increased charges on no-fault patients in order to make up for deficits in other segments of their business,” writes Kuhnmuench.

Even Detroit’s Duggan, the former hospital executive, says he understands the need for a so-called “triple rate”—typically the multiple charged by a hospital that must pay for expensive on-call specialists attached to a trauma center.

But the insurance industry balks at the idea of having no price list at all, which is basically what hospitals have when it comes to what they are allowed to charge for care related to an auto accident.

So far, the courts have sided with the hospitals, one example being a 1996 ruling by Michigan’s Court of Appeals that affirmed the right of Traverse City-based Munson Medical Center to charge a “customary” amount, regardless of whether it routinely accepted less than that amount. That case, which was brought to the Court by AAA, also said that an insurer could not use a payment schedule used for workers’ compensation to determine the amount of reimbursable charges.

So far, the courts have sided with the hospitals, one example being a 1996 ruling by Michigan’s Court of Appeals that affirmed the right of Traverse City-based Munson Medical Center to charge a “customary” amount, regardless of whether it routinely accepted less than that amount. That case, which was brought to the Court by AAA, also said that an insurer could not use a payment schedule used for workers’ compensation to determine the amount of reimbursable charges.

In the Munson case, the hospital argued that unpaid charges—which amounted to slightly more than $100,000—were “reasonable” because none of the other insurers had objected.

AAA also argued, unsuccessfully it turns out, that its payments to the hospital reflected what the charges should have been, reasoning that because other health care insurers (including Medicare and Medicaid as well as Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan) wouldn’t pay, the unmet costs were shifted to the auto insurer.

On the other side of the argument are politicians like Oakland County Executive Brooks Patterson, who in early December presented his case against the impending legislation to state representatives, calling Senate Bill 248 (the one that passed in May) a “Trojan horse” that should be seen as an example of corporate greed.

Patterson, who was seriously injured in a 2012 car accident (his driver was paralyzed) adamantly opposes the proposed State House legislation (HB 248), saying the estimated $20 billion in the Michigan Catastrophic Claims Association fund would be “instantly pounced upon by the insurance industry and divided up among them.”

That’s nonsense, says the IIM’s Kuhnmuench, who adds that the MCCA was first formed after smaller insurance companies were facing insolvency, the result of them having to book lifetime unlimited medical claims.

Kuhnmuench does say insurance companies would like to restructure the MCCA, but wouldn’t touch the funds that are there now. “Those are costs that are still on our books, part of the cost of insurance.”

It’s not only the insurance companies that take notice of the lifetime unlimited medical coverage provisions of Michigan’s no-fault environment.

Medicare, the federal insurance program for seniors, has a rule that specifically excludes Medicare from paying for care that is the result of a car accident until the auto insurance coverage runs out.

In Michigan, of course, unlimited lifetime medical coverage for PIP never does.

Seniors, who have Medicare benefits, should also be able to opt out of the mandatory coverage in favor of a lesser amount, says the IIM.

One only has to drive a few miles of freeway through Detroit to see another economic signpost that Mike Duggan says is having an effect, that being the proliferation of billboards by lawyers seeking new clients in car accident cases.

“Detroiters have the same incidence of car accidents as suburbanites,” he told Detroit City Council. “But Detroiters file twice as many personal injury claims.”

And the amount of the medical claims filed is also greater in Detroit, according to Duggan’s argument, an average of $60,000 versus the $30,000 average claim of a suburban driver.

Duplication of benefits

But a bigger issue for Detroit’s Duggan and the insurance industry (which supports the inherent choice built into the D-Insurance proposal) is what proponents say amounts to a duplication of benefits, from both auto insurers and health care insurance providers.

“At a minimum, consumers ought to have the right to choose and one of those choices would be the unlimited PIP, as well as something less than unlimited benefits,” says the IIM’s Kuhnmuench.

Yet another issue that seems to undermine the overall sustainability of Michigan’s auto insurance environment is the percentage of drivers who effectively “opt out” of the game altogether, albeit illegally.

Even the legal imperative of a vehicle owner to demonstrate they have auto insurance before getting their state-issued registration sticker is not without its problems, says Kuhnmuench.

“We’ve got a healthy fraudulent insurance industry in Michigan, one where it’s easier to pay the fine and get the license (than it is to comply with the law). People are known to purchase auto insurance and cancel the next day,” he adds.

A “crackdown” of the practice included a one-day snapshot of certificates by the state’s Secretary of State in 2013. Some 16 percent of certificates were found to be fraudulent or otherwise invalid.

For its part, health care providers, represented by the Coalition Protecting Auto No-Fault, argue that D-Insurance is full of “unintended consequences” that leave auto accident victims vulnerable.

“These caps on auto insurance coverage will put Detroit’s most seriously injured auto accident survivors at risk of having to choose between going without necessary medical rehabilitation treatment and falling into bankruptcy,” says John Cornack, CPAN’s president. “D-Insurance will shift the cost of caring for these types of injuries from insurance companies onto taxpayers.”

Laura Appel, senior vice president of strategic initiatives at the Michigan Health & Hospital Association (a member of the CPAN group), acknowledges that there may be differences between what individual hospitals charge for a set of services, sometimes depending on the complexity of care offered or even the type of hospital that is providing that care.

But while those fees (called “charge masters”) must, under federal law, be the same regardless of who is paying the bill, there remains variability in what a hospital will ultimately accept in payment.

With Medicaid, for example, “we don’t get to argue on the amount” accepted, says Appel.

She adds that current proposed legislation does not deal with any requirement on the part of insurance companies to offer a long-term reduction in their rates.

What the MHA has talked about is the idea of offering a 20 percent reduction in every MHA hospital’s charge master, freezing those for three years and then updating the rates after that period by the Consumer Price Index for medical services.

The insurance industry’s counter to that idea (which it says is an old one) is that the base charges are too high and real change in insurance rates will only come when companies can predict what their costs will be over time.

Which is one reason the industry supports D-Insurance.

“Statistics tell us that well over 90 percent of all motor vehicle (PIP) claims result in medical expenses of less than $25,000 which is the minimum benefit level under the “D” Insurance proposal,” says Kuhnmuench of the IIM.

Following the math, less than 1 percent of those injured in an auto accident might not have coverage beyond the minimum requirements of D-Insurance, but Kuhnmuench believes that coverage would likely be available (even after an accident) through provisions of the Affordable Care Act, which would (at least in theory) not exclude existing conditions.

In mid-December, the winds of compromise began blowing, with State Rep. Brian Banks, a Detroit Democrat and minority chairman of the House Insurance Committee, introducing two bills that would offer a 12 percent rate reduction (and a $500 tax credit to insurance companies for every previously uninsured household that signs up under the program).

Detroit’s Duggan, who had hoped the D-Insurance proposal would be in place by now, may not be totally surprised by the ongoing fight.

“If we look at what’s going on in Lansing today,” he told City Council last May, “the insurance companies have lobbyists, the hospitals have lobbyists, and the trial lawyers have lobbyists. But for the 50 percent of Detroiters who don’t have car insurance, the question is, who’s going to speak for them?”