Bring up the subject of sports in America and then ask someone to list the most popular games going.

Go ahead. We’ll wait.

The answers will invariably include baseball, football, hockey and basketball, represented by the pinnacle professional leagues behind each: Major League Baseball, the National Football League, the National Hockey League and the National Basketball Association.

But a growing number of fans in a sport that is arguably the most popular on the planet will make the point that a fifth—what we still insist on calling soccer and what everyone on the planet insists is football—belongs on the list.

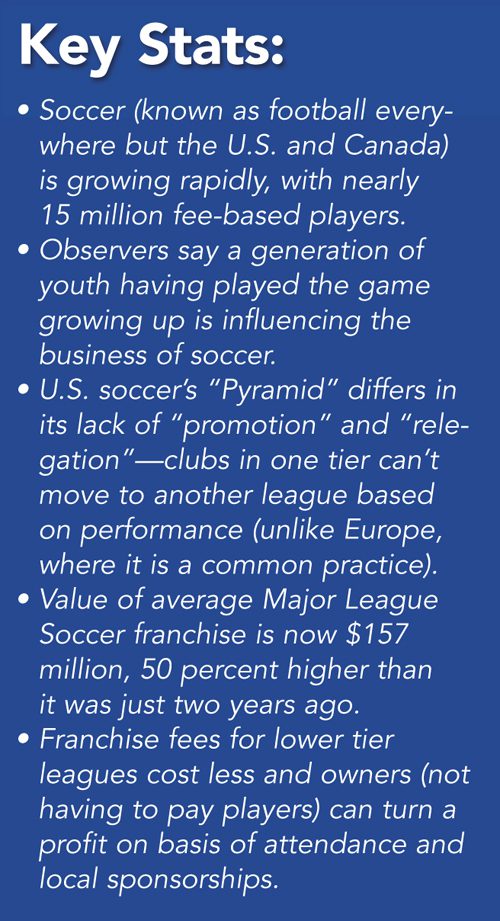

Fans of the game, whatever it’s called, appear to be winning their argument, if for no other reason than the sheer numbers: according to the 2009 U.S. Census, some 13 million Americans were playing the sport, behind only basketball and baseball (both hardball and softball). In 2015, a variety of sources (compiled by Statista.com) estimates the number of fee-based players to be as many as 14.74 million (compared with the site’s 2009 equivalent of 11.1 million—those who paid to be on a team).

We’ll get into discussing the almost dizzying complexity of soccer’s organizational structure a little later, but suffice it to say, the sport is beyond simply being on the radar: for many interested in not only continuing to follow a sport they have grown up enjoying (and playing), soccer seems to have reached a kind of critical mass from a business perspective.

The soccer ‘pyramid’

Let’s start with the top of what some call the soccer pyramid in the United States (and, in this case, Canada).

The organization is Major League Soccer, a 20-team league (including three in Canada) that was first launched in 1995 with 10 teams in its inaugural 1996 playing year.

From a financial standpoint, some of the most significant numbers come in the form of the value of an MLS franchise, the average of which is $157 million, according to Forbes magazine, which has tracked that number over time (two years ago, the average franchise was said to be worth $103 million).

And then there’s the arguably even more important number: attendance.

In 2015, Major League Soccer matches boasted an average 21,574 spectators, the highest attendance in its history and the third-highest in professional sports (behind the NFL and baseball’s MLB but ahead of hockey’s NHL and basketball’s NBA). Most impressively, that number is 64 percent higher than it was in 2000 (when 13,756 was the average).

Total attendance at MLS games was 7.3 million in 2015, more than tripling the 2.2 million that paid to see a game in 2002.

Another Duggan has his eyes on Detroit

For Dan Duggan, owning a team like his Michigan Bucks, a member of the Premier Development League that’s based in Pontiac, has never been about the money.

Indeed, in the 20 years since the Bucks were formed (by Jim Duggan, Dan’s brother), the team has been a place for college-age players (the term Under 23 is commonly used) to go professional.

But that doesn’t mean Duggan, whose brother Michael is Mayor of Detroit, isn’t interested in the business side of the sport.

A sales consultant by profession (he lives in Michigan but works for a company based in Cleveland, Ohio), Duggan remembers a day when the trajectory of the Bucks was decidedly different than it is today.

The idea was that the Bucks, called the Mid-Michigan Bucks in homage to its original home of Saginaw (there was a PDL team in Detroit at the time), would eventually become a professional team.

Indeed, Duggan had originally wanted to be a member of the now-defunct National Professional Soccer League, but was prevented from doing so by virtue of the Detroit Rockers holding the franchise in Detroit.

Indeed, Duggan had originally wanted to be a member of the now-defunct National Professional Soccer League, but was prevented from doing so by virtue of the Detroit Rockers holding the franchise in Detroit.

The Rockers folded in 2002 and he moved the club to Pontiac a year later.

“That was when we started a campaign to join the MLS,” Duggan says. “We were playing MLS teams in the Open Cup and we beat a team in 2000. We even hosted the New York New Jersey Metro Stars [now the New York Red Bulls] and used that game as our catalyst.”

That was a day when $5 million would buy you a franchise (remember, the current average price is $157 million).

But Duggan and his partners would have needed a $100-million stadium to pull off the complete idea and few thought it was going to make it.

“In everyone’s defense, it wasn’t the perfect sports model,” says Duggan. “It was okay if you had extra money to do it, but not right then.”

That, of course, was then. What’s changed now—and what has Duggan increasingly optimistic about the idea of having a professional team in Detroit—is the idea of joining the United Soccer League.

For at least a year and a half, when he first announced a plan to acquire a franchise in the USL, a Tampa, Fla.-based organization with 29 teams (four of which were announced in the latter half of 2015), Duggan has been pursuing what he envisions as the model the Orlando FC pursued, which was a member of the USL from 2011 to 2014 and which now is a member of MLS.

While Duggan’s plans to join the USL are certainly not firm (he will need to finalize a deal to build a downtown Detroit stadium that he says will seat 7,000-8000), he is certainly talking like an optimist, although media reports in 2014 had him eyeing a 2016 season, which he says is now lost.

“We couldn’t do the deal fast enough,” he says now, a year after attending the World Cup in Brazil, in which he participated in numerous meetings that were held between games.

What is clear is that the energy behind the business of soccer is real enough to have an entire generation of Americans who grew up with the game excited about its future.

Lansing United owner finds niche

One of those is Jeremy Sampson, a Lansing-based former media professional who now owns Lansing United, a member of the fourth-tier National Premier Soccer League, which is roughly at the same level as Duggan’s Michigan Bucks.

Sampson, whose day job is with the state of Michigan’s Treasury department, says the idea of owning his own business and seeing an opportunity to join the affordable NPSL intersected about two and a half years ago (it debuted in May 2014).

While Sampson said he’s not comfortable discussing specific financial details of the club, he remains positive about the quality of the NPSL business model, which focuses on developing the support of the community, something he said has happened in Lansing.

“They’ve wrapped their arms around us as a club,” he says, referring to home game attendance that has averaged about 1,000 after two seasons (a third begins in May 2016).

Sampson, who played soccer as a youth, but whose high school didn’t offer the game, says he has a lot of admiration for those who have a broader background—”maybe because I’m not any good at it!”

As a business person, he remains confident that the sport will remain popular and even grow, which he says is a critical part of building an infrastructure that will ultimately include players.

“It’s giving the young people something to strive for,” says Sampson. “It’s showing that we have something they can achieve at a higher level.”

Switching leagues is one way to grow

One of Sampson’s team at Lansing United during those first two years was Eric Rudland, who was general manager and head coach of the club before moving to AFC Ann Arbor this season. He is now serving as head coach and technical manager at AFC Ann Arbor, which wrapped up its second season as a member of the Great Lakes Premier League.

Rudland, who works full-time in the sport (he helps with college programs and with youth clubs during the off season), will help with AFC Ann Arbor’s transition next season to the NPSL, effectively going head to head with his former colleagues at Lansing United.

Joseph Barone, a banker and currency trader by profession who has coached the Brooklyn Italians and is currently chair of the NPSL, may be one of those most familiar with the business model behind today’s game.

At its core, the league would be considered an adult amateur national league, although the term “amateur” has nothing to do with professionalism, notes Barone, who is vice president of the Brooklyn Italians, itself a not-for-profit entity that’s owned by a board.

“The players aren’t paid but their expenses are covered,” he explains.

Distinct from the USL, the NPSL is a member-driven organization that has teams paying $12,500 for a franchise and $5,000 a year in ongoing fees.

From there, the expenses are largely dictated by how big a team’s owner or owner wants to become.

“You can operate on a $100,000 budget or a $500,000 budget,” says Barone, who says his Brooklyn Italian club, which plays in a local high school and has been in the same neighborhood since being established in 1949, is “very limited” in how big it can grow.

Back to discussions about a team for Detroit

The wildly popular Detroit City FC, also a member of the NPSL, appears to be taking a novel approach to its growth, with the membership group undertaking what it calls a community investment campaign, the idea being to raise some $750,000 for a renovation of the 79-year-old Keyworth Stadium, which is owned by Hamtramck Public Schools.

In October, the club announced a partnership with Sidewalk Ventures, LLC, MichiganFunders (described as an equity crowdfunding organization), and Hamtramck Public Schools.

Under the terms of the deal, the stadium will continue to be owned by Hamtramck Public Schools, but Detroit City FC will retain the right to host 25 games and community events throughout the year under a 10-year lease agreement.

Individuals funding the venture must be Michigan residents. In return they will receive an unspecified financial return if the goal is met. Investments can be as little as $250 and as much as $10,000.

Club co-owner Alex Wright says having sold out every game in the 2015 season was “a clear sign” that Detroit City FC was ready to take this step.

“On our way to saving history [a reference to the significance of Keyworth Stadium], Michigan residents will have the opportunity to make history by joining us to complete what we believe to be the largest community-financed project in U.S. sports history.”

It is not clear how a successful project would impact any plans Dan Duggan may have for a future USL franchise, particularly since co-owner Wright has indicated in at least one media report that “conversations continue with investors to take us to a pro level and move up to a higher professional level.”

A renovated Keyworth Stadium, Wright told the Detroit Free Press, “would meet those immediate needs. Our goal is to be Detroit’s soccer team. Undeniably. Unchallenged. Detroit’s soccer team. To do that, we need to play a longer season at a professional level in a venue that we have more control over. This helps address that last component.”

Promotion and relegation—foreign words for U.S. soccer

If Wright’s comment of moving up “to a higher professional level” caught your eye, consider one of the most significant differences from the U.S. soccer landscape, in all its varied forms, and that which exists in other parts of the world.

That difference is most clear in one word that has particular significance in “soccer speak”—relegation.

In European soccer/football in particular, teams finishing near the bottom of a higher-level division are automatically sent down (relegated) to the next lowest level, while those in anything lower than the top tier are promoted to the higher level.

In essence, the concept is designed to (and works at) keeping teams hungry enough to compete right to the end of their season.

The worst example of not having relegation may be in a league like the NHL, where the worst team typically gets the first choice in a new player draft.

But there is no relegation (or its promotion counterpart) in American soccer, although some teams have been known to move to a lower level league for financial reasons.

At least one organization, the non-profit, non-partisan Public Religion Research Institute, says today’s young people are more than twice as likely to have played youth soccer than the equivalent youth level of (American) football—22 percent versus 8 percent.

While Daniel Cox, the PRRI’s director of research, acknowledges that soccer’s competitive advantage in attracting young athletes “does not necessarily mean it is destined to surpass football in popularity,” youth sports can create lifelong fans.

“Americans who grew up playing soccer are more likely to have a greater appreciation for the sport and often serve as its mot ardent fans,” Cox wrote in a column for the Huffington Post.

Even as he acknowledges that American football remains the “undisputed leader . . . by every measure,” Cox says that may change over time.

“The growing popularity of youth soccer in the U.S. means football may soon have to compete for fans among a population that grew up playing and remain loyal to (the game).”

Soccer’s future in the U.S. looking good

Peter Alegi, a professor of history at Michigan State University who focuses on the relationship between popular culture and politics, especially soccer, says the visibility of the sport (whatever you choose to call it) has passed any sort of tipping point that may have existed in the past.

And at least from a business perspective, that may be one of the key points in the history of a successful American soccer scene.

“It’s no longer a question of whether professional soccer is going to survive, but where is the next franchise going to be based,” says Alegi. “There are serious questions about profitability and some are concerned about viability, but the value of the franchises has increased.”

From the economic perspective of the game, the business that’s represented by youth soccer is one that can’t be ignored.

“There’s a soccer economy that’s definitely growing,” says Alegi. “From equipment, the cost of travel, and even recruiting for colleges, there continue to be ramifications for the economy.”

While it hasn’t been discussed, one issue that Alegi hasn’t overlooked, at least from an academic standpoint, is the one involving gender equality in the sport.

“Women’s soccer needs to be treated more fairly and equitably,” he says, even while making the point that the game in the U.S. is currently “well developed.”

What may help keep that momentum going in the right direction, says Alegi, are initiatives such as subsidizing the national team, “which may help get girls to play, along with supporting facilities and coaching.”

Finally, there may have been a role in advancement of the sport from an area that may seem obvious only to those who hear of it first, that being the video game market.

FIFA Football (also known as FIFA Soccer), now in its 16th iteration (it was first launched by EA Sports, part of Electronic Arts, in 1993) is considered the best-selling sports video game franchise in the world, with more than 100 million copies sold. It is also one of the best-selling video game franchises.

More, by the way, than EA Sports’ Madden NFL.