When Devita Davison, her Brooklyn, N.Y., home destroyed by Hurricane Sandy, returned to her roots in Michigan, she took a chance and accepted a co-director’s position at what was essentially a startup, even though FoodLab Detroit is a nonprofit organization.

Davison had come back to Detroit to regroup and had every intention of returning to her old life in New York. But what impressed her was not only the commitment of FoodLab founder Jess Daniel, but the fact that very little time and money was wasted in managing an organizational structure. FoodLab was “very lean, nimble, flexible.”

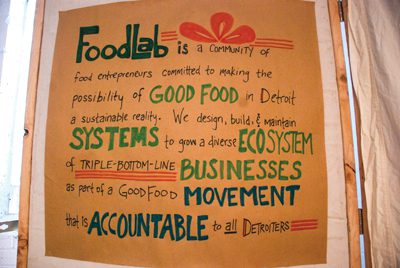

FoodLab, essentially a group of locally owned food businesses that share resources, spoke her language of idealism mixed with business pragmatism, and she was sold.

In many ways, it was a continuation of what Davison was doing in Brooklyn, which had a jump on Detroit by a few years in fostering grassroots entrepreneurialism in local food.

“We like to think that we are part of a larger good-food movement,” Davison said. Indeed, she said, it’s part of a larger movement to create opportunity for “traditionally marginalized” communities, including African Americans, Southeast Asians, veterans and women.

“The mission of the organization is to create systemic change. We’re not talking about, ‘Oh, we want to help entrepreneurs grow their businesses.’ We want to do that. Of course we do. But we also know if we really want to create change and an economy that is equitable, fair and just for all, we’re going to have to … ask, ‘What are the systemic challenges that prevent them from starting, growing, and maintaining a business? That’s how you create change, when you create change in a system.”

The most obvious challenge to these communities is access to capital. But, said Davison, back up and ask why this access is practically nonexistent. It’s because they’re first-time business owners who lack a credit history. Couple that with the fact that the failure rate in the food business is high, no matter what your ethnicity or economic background. As a result, banks are reluctant to finance anybody.

FoodLab’s solution is all about “ecosystem,” Davison said. Because “traditionally marginalized entrepreneurs” rarely get a seat at the table, FoodLab creates opportunities for networking among its own first, then with the larger financial world later.

The important thing, first, is market validation. In the food business today, there’s never been a greater opportunity to accomplish this. Time was, you’re in the food business, you plunk down your life savings, and that of your friends and family, and open a restaurant. Today, there are many steps in between your home kitchen and a brick-and-mortar restaurant.

“Start with a mobile coffee cart or a food truck,” Davison said. “Or take advantage of vacant space in Detroit and do a pop-up. The barrier to entry for the food business now is a lot lower than it was five, six, seven years ago.” Today, she said, it’s “culturally appropriate” to go these alternative routes. And, more importantly, potential lenders are now paying attention.

“Now, with a small amount of money they can start to organically grow and scale their business. And, guess what? Once they start to get market validation, once they start saving up money, then they can move on to the next step,” which could be a meeting with a Fifth-Third or a Chase, Davison said. “The road map is different now.”

So, how can FoodLab Detroit help a collection of startup food entrepreneurs, many coming from disadvantaged communities, find their way onto the right road? Founder Jess Daniel has the organizational ability and the idealism. What Davison brings is the real-life business experience … and Oprah.

Yes, that Oprah. In September, Davison and her Detroit Kitchen Connect won a $25,000 grant from Oprah Winfrey and Toyota. And, yes, she got to meet the celebrated icon.

But before getting into what that means for FoodLab, it’s necessary to go even further back into Davison’s past to show how she got there.

Roots in branding

When she first moved to New York almost 20 years ago, Davison worked for the branding and licensing department of Hearst Publications, which at the time was looking for ways to leverage its well-known magazine titles to earn licensing fees. “I helped create things like the Good Housekeeping salad dressing, or Esquire barbecue sauce,” she recalled, laughing.

Her friends in Manhattan were accusing her of selling out.

Her friends in Manhattan were accusing her of selling out.

“They were in Brooklyn creating everything from scratch, homemade … there was a whole movement that was happening in Brooklyn way before we started talking about local-food entrepreneurship. This was back in 2008.”

Hearst eventually disbanded Davison’s department and she took a buyout, freeing her up to use her market knowledge to sell the products her friends were making. She opened up a retail store in Brooklyn and bought her first home in 2011. Then came Hurricane Sandy, which drowned her life savings under seven feet of water.

So, it was back to Southfield to live with her parents while she regrouped. Then she met Daniels at FoodLab and “she totally changed my life” with her enthusiasm for growing a local-food movement in Detroit. Davison was surprised that there was no infrastructure such as she enjoyed in Brooklyn, no incubator kitchen. Instead, FoodLab’s members were cooking in homes, churches, even at the DIA and DSO. Davison was asked to design a better system than this “gray market” of catch-as-catch-can kitchens.

Davison is careful not to claim sole credit for all FoodLab’s 114 members’ successes. They are not a venture capital fund. They don’t provide the money, but they do partner with organizations that do. For example, there’s a member who got a $500,000 Kiva loan to buy equipment. FoodLab works with Kiva to vet entrepreneurs and serve as character references.

Another member, Lisa Ludwinski, who runs Sister Pie, a local baked-goods company, was recently awarded $50,000 in the Hatch Detroit competition, at least in part due to coaching from FoodLab Detroit.

“We’re very excited for her,” Davison said. “She will be opening a brick-and-mortar next year on the East Side in West Village.”

Building through networking

It’s one thing to say you want to build a local-food economy, but facts on the ground sometimes can get in the way—such as a lack of food processing plants in Detroit and across the state. So, like everything else about FoodLab’s mission, the solution is found first on a small scale, through networking.

FoodLab has partnered with Hopeful Harvest Foods, a social enterprise at Forgotten Harvest, which collects and distributes surplus food, to train a workforce that will process and package food in Oak Park.

FoodLab has partnered with Hopeful Harvest Foods, a social enterprise at Forgotten Harvest, which collects and distributes surplus food, to train a workforce that will process and package food in Oak Park.

But, Davison said, many of FoodLab’s entrepreneurs would rather not outsource the processing. For them, a partnership with Ferndale-based Garden Fresh would make more sense. Garden Fresh is creating an accelerator program to train workers on how to automate packaging and processing.

And the next step is a partnership with Eastern Market, which could put them in touch with Whole Foods and JP Morgan Chase through Shed 5.

This, Davison said, is how local-food entrepreneurs, many of whom come from traditionally disadvantaged communities, move from their own kitchens to big stores and possible investors, building slowly using the resources of FoodLab.

“It’s going to take us some time in Detroit, but we’re building this thing out,” Davison said.

And, getting back to her grant from Oprah (and even appearing onstage with her), the national attention she received sure didn’t hurt.

“To be honest, life for me has not changed much, pre- or post-Oprah. However, life for FoodLab, the ability to create, design and maintain systems that support the growth of entrepreneurs in the food sector, has changed tremendously.”

Now, people expect great things and ask her all the time: You’ve designed a project that grabbed national attention. So, what’s next?

“I tell myself all the time, ‘I hope my first album is not my best album.’”