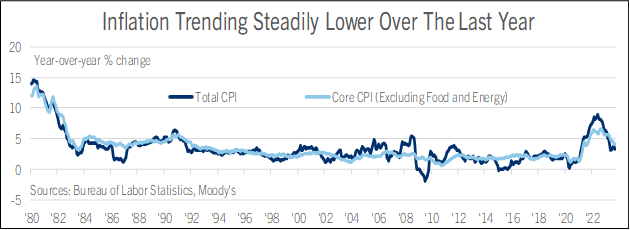

The CPI index was unchanged in October, below the consensus forecast for a 0.1% increase. In year-over-year terms, the CPI slowed to a 3.2% increase from 3.7% in September; the median forecast of private economists was for a more gradual slowdown to 3.3%. Food prices rose 0.3% on the month while energy prices fell 2.5% as gasoline dropped a seasonally-adjusted 5.0%. The core CPI excluding food and energy rose 0.2%, also below the 0.3% consensus forecast.

From a year earlier, core CPI slowed to 4.0% from 4.1% and was the lowest in a little over two years; this modestly undershot the consensus forecast for core inflation to hold steady.

The biggest driver of October’s cooler-than-expected inflation was the month’s drop in gas prices. Domestic crude production hit a new record high in October. With higher refinery output, domestic gasoline inventories rose above their 5-year average for this time of year, putting downward pressure on prices at the pump. Consumer surveys show Americans are concerned that war in the Middle East could push gas prices back up in coming months, renewing inflationary pressures. But so far that isn’t happening, and gas prices are actually lower than when war broke out in the beginning of October.

The shelter components of the CPI are rising more slowly in year-over-year terms. The CPI’s rent component was up 7.2% on the year in October, down from a peak of 8.8% in April, while owners’ equivalent rent of primary residence (how the CPI measures shelter costs for homeowners) slowed to 6.8% from 8.1% over the same timeframe. This slowdown reflects the lagged passthrough of much slower increases of house price indexes in 2023 than in 2022 and 2021, as well as slower increases in new residential leases. This delayed pass-through of HPIs and new leases will continue to slow core CPI in 2024. To look through this effect and track the underlying trend, the Fed is monitoring a basket of service prices excluding food, energy, and shelter. These core service prices excluding shelter rose 0.3% on the month and 3.9% on the year in October, up from 3.7% in September but still the second-slowest year-ago increase since January 2022. CPI core services less housing rose 0.2% on the month and slowed to 3.8% from 3.9% in year-over-year terms, the slowest since December 2021.

Within core services, individual price components were mixed. Transportation service prices rose 0.8% on a 1.9% increase in motor vehicle insurance, reflecting lagged effects of big increases in vehicle prices and repair costs in 2021 and 2022. On the other hand, car and truck rental rates fell 1.5% on the month and 9.6% on the year. Airfares fell 0.9% on the month and 13.2% on the year. Medical care services rose 0.3% with hospital services up 1.1% and health insurance up 1.1% after a 3.5% decrease in September (The CPI’s methodology captures health insurance costs poorly, showing an improbable 34.0% year-over-year decline in October).

Outside of core services, durable goods are making a big contribution to lower inflation. New vehicle prices fell 0.1% in October, and used car and truck prices fell 0.8%. From a year earlier, new vehicles are up a modest 1.9% while used cars and trucks are down 7.1%. Competition for market share among carmakers is intensifying especially for EVs; car dealers are offering more incentives to close sales and that is holding down increases of new car prices. There are deals to be found off car dealer lots, too: Television prices are down 9.4% on the year, computers peripherals and accessories are down 5.7%, and smartphones are down 12.0%, the largest year-ago decline on record.

October’s cooler-than-expected CPI report keeps the Fed on course to hold interest rates steady at their next few monetary policy decisions. Most recent U.S. labor market data, like October’s slower payroll job growth, higher unemployment, and moderating wage growth, parallel the CPI in pointing to a cooling economy and lower inflation ahead. There are still upside risks to prices. Real GDP grew a faster-than-expected 4.9% annualized in the third quarter, a pace which could cause inflationary pressures to reappear if it is sustained. And the federal deficit jumped 23% in the government’s fiscal year that ended in September despite the economy recovering fully from the pandemic-era recession; federal interest expense will rise in the coming fiscal year, which will keep the deficit large and could revive inflationary pressure.

Even so, the economy’s path toward a more normal pace of price increases is clearer after the CPI report’s release. Reflecting this, bond markets are pricing in lower odds of the Fed making further interest rate increases at their next few monetary policy decisions, and higher odds of them cutting interest rates in 2024. The yield on the two-year Treasury note has fallen to the lowest since the first half of August. Longer-term Treasury security yields are down too, though not by as much; the 10-year Treasury note yield is still about a quarter percentage point higher than in the first half of August.

This multi-speed normalization of interest rates will likely continue next year. The Fed is forecast to cut interest rates gradually, while bond yields at two-year maturities fall more, since they embody forward-looking expectations for monetary policy to normalize further over the next couple of quarters. Yields of longer-term bonds like the ten-year Treasury will likely fall less than two-year yields, since large fiscal deficits put upward pressure on the long end of the yield curve, and financial markets are likely to price in more optimism that the economy can return to normal rates of inflation and economic growth without a severe downturn.

Bill Adams is a senior vice president and chief economist at Comerica. Waran Bhahirethan is a vice president and senior economist at Comerica.