• The Fed raised the federal funds rate 0.75 percentage points June 15, the largest hike since 1994.

• FOMC members expect weaker growth and higher inflation than in their prior forecasts released in March.

• Fed policymakers see themselves on course to raise their benchmark rate another 1.75 percentage points by year-end, and another 0.50 percentage points in 2023.

• There are near-term upside risks to interest rates from inflationary pressures, and medium-term downside risks from a cooling economy.

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) raised the Federal Reserve’s benchmark federal funds target by three quarters of a percent at the June 15 decision, to a range of 1.50%-to-1.75%. The vote was 8-1, with Kansas City Fed President Esther George favoring an increase of 0.50%. This hike was a big deal, since the last time the Fed raised rates so much in a single go was in 1994. It matched what financial markets priced in the morning before the decision, but that was after a big reset of expectations over the prior week. Financial markets had priced in a hike of half-a-percentage-point in early June, then shifted to expect a three-quarters-of-a-percent hike just two days before the decision, after a Wall Street Journal story (widely suspected to source a leak from the Fed) indicated a hike of three quarters of a percent was likely.

The Fed’s policy statement was little changed from May, but updates to the FOMC’s quarterly economic projections a.k.a. “dot plot” show members expect both growth and inflation to be worse than expected in the prior dot plot from March. The dot plot’s median forecast for real GDP (half of FOMC members are more optimistic, half are more pessimistic) marked down the forecast for 2022 by more than a percentage point, to 1.7% from 2.8%, and lowers the forecast for 2023 to 1.7% from 2.2%. This forecast is for real GDP growth in the fourth quarter of the year, relative to the fourth quarter of the previous year, not for annual growth (whole year versus whole prior year). With weaker growth expected, the median dot anticipates an increase in the unemployment rate over the next two years. It sees a rise from 3.6% in May to 3.7% at the end of 2022 and 3.9% at the end of 2023. Back in March the median dot expected the unemployment rate to hold at 3.5% over that timeframe.

FOMC members expect considerably higher inflation than they did in March, since energy and food prices have surged after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and housing prices rose more than forecast in recent months. The median FOMC member expects inflation measured by the personal consumption expenditures deflator (PCE inflation, the Fed’s preferred measure) to close 2022 at 5.2% in year-ago terms, up from the 4.3% they forecast in March. The PCE inflation forecast for year-end 2023 is little changed, 2.6% versus 2.7% in the March dot plot.

Separate from these forecasts, the dot plot also summarizes FOMC members’ expectations of the appropriate course of monetary policy. That’s “what they should do,” not “what will happen.” The median FOMC member wants to see another 1.75% in rate hikes by the end of this year, followed by 0.50% more over the course of 2023. That would raise the federal funds rate to a range of 3.25%-to-3.50% by the end of 2022, and to 3.75%-to-4.00% by the end of 2023. Chair Powell provided some guidance during the press conference after the decision describing the Fed’s likely path to those levels. He thinks the next FOMC decision on July 27 will probably be a choice between another 0.75% hike and a 0.50% hike, and he does “not expect moves of [0.75%] to be common.” The Fed sees itself on a course to hike 0.75% in July, 0.50% in September, and a quarter percentage point at the November and December meetings, followed by two more quarter percentage point hikes in early 2023.

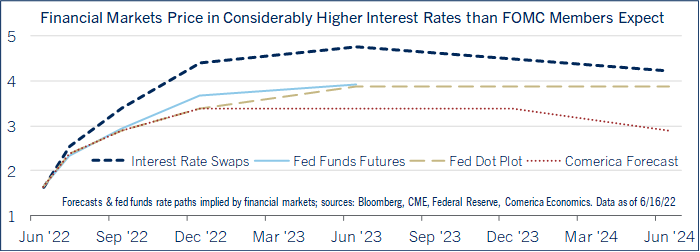

Following the June Fed decision, Comerica is revising its forecast for the federal funds rate to foresee a rise to a range of 3.25%-to-3.50% at the December FOMC meeting, ending this rate hike cycle. Relative to our June forecast, this raises the peak federal funds rate by half a percentage point, and pulls forward the end of the hiking cycle by one quarter. In the revised forecast, the fed funds rate will hold unchanged throughout 2023, then be cut by a quarter percentage point at each of the Fed’s decisions in March, June, September, and December 2024, to an assumed terminal rate of 2.25%-2.50%. Risks to the Fed’s hiking plans are to the upside over the next few months, with tight global inventories of crude oil and refined petroleum products putting upward pressure on energy prices and inflation. But risks to the Fed’s plans in the winter and onwards are to the downside, since a cooling housing market will slow house price increases and core inflation—shelter accounts for about two fifths of the CPI basket. Financial markets price in faster hikes than anticipated by this forecast, or by FOMC members (See chart). As of June 16, fed funds futures imply the Fed funds rate rises to 3.50%-to-3.75% in December 2022 and 3.75%-to-4.00% in June 2023. Interest rate swaps price in an even steeper hiking cycle, with the fed funds rate in December 2022 at a range of 4.25%-to-4.50%, and the most likely rate in June 2023 at 4.75%-to-5.00%.

Faster rate hikes mean risks to economic growth are skewed to the downside. Comerica forecasts for annual real GDP growth of 2.8% in 2022 and 1.7% in 2023, or 1.7% and 1.4% respective increases in the fourth-quarter-to-fourth-quarter terms the Fed uses. Downside risks mean the economy is more likely to underperform this forecast than surprise to the upside. A weaker growth outlook puts the economy closer to slipping into a recession. Recent economic data are already trending softer. Initial claims from unemployment insurance are up 63,000 over the last three months, retail sales fell 0.3% in May, housing data are normalizing, and business and consumer sentiment are down since Russia invaded Ukraine. Considering these data, as well as the faster tempo of rate hikes laid out by the Fed, the likelihood of a recession starting in 2022 is around two-in-ten, up from one-in-ten in early June. The risk of a recession starting in 2023 is up to around three-in-ten from one-in-four.

The Fed did not disclose plans to sell mortgage-backed securities (MBS) at the June decision, a step that will be necessary to reduce the Fed’s holdings at the rate they target ($17.5 billion per month through September, $35 billion per month subsequently). Average interest rates for a 30-year mortgage have jumped to near 6% for the first time since 2008, up from near 3% in late 2021, and mortgage applications for home purchase had the worst month since 2016 in the four weeks through mid-June. Policymakers could be waiting to see how much the housing market slows before committing to a plan for MBS sales, which could be announced in September.

Bill Adams is senior vice president and chief economist at Comerica.