This really isn’t a story about how to start a business, even one as successful as Zingerman’s Deli and the Zingerman’s Community of Businesses that have sprouted up over the years, all of them in or around Ann Arbor.

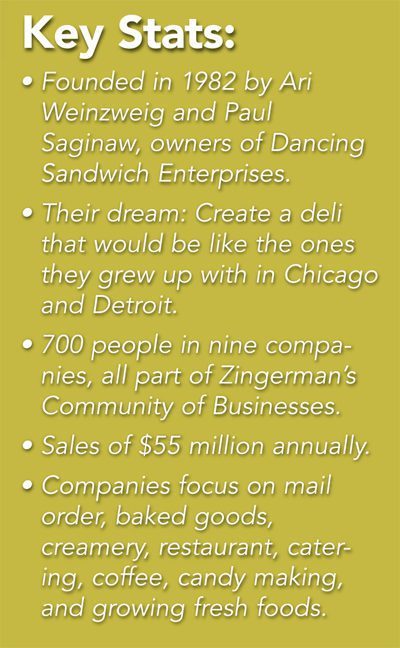

It is, however, a story about how two former University of Michigan students—not even college friends—ended up having one of those reminiscent conversations people sometimes have, in this case the topic being about how this little slice of 1970s Ann Arbor didn’t really have the kind of delicatessen that the pair enjoyed where they were growing up (in Detroit and Chicago respectively).

Those two—Ari Weinzweig of Chicago and Paul Saginaw of Detroit—stumbled into one another’s life when Weinzweig, who had studied Russian history and decided he’d like to stay in Ann Arbor, began washing dishes at Maude’s, a restaurant that was being managed by Saginaw.

Over periodic chats, the conversations about “what it would be like” to start a deli began to take place.

Weinzweig started prepping food and line cooking and even managing at least pieces of the kitchen operation, but eventually he says he became somewhat frustrated by the limits to what he could do. “I wanted to do things like bring in better ingredients and there was so much more that could be done, but they were happy just to stay where they were, so I gave two months’ notice, not really knowing what I was going to do.”

Two days later, Saginaw called to let him know that a building that might be suitable for their deli idea had become available and would he like to have a look?

That was November 1981. Four months later, on March 15, 1982, Weinzweig, Saginaw and two staffers were behind the counter at a 1,300-square-foot building on the corner of Kingsley and Detroit, making sandwiches and cutting bread and cheeses at Zingerman’s.

It might have been Greenberg’s (the deli to be named after one of the Monahan’s customers Saginaw had waited on) but that came to a screeching halt when an actual Mr. Greenberg informed them that he had registered the name and was going to franchise the idea, beginning with a deli in Southfield. And, no, they couldn’t use the name.

“We had to change it,” recalls Weinzweig, citing a scientific process that began and ended with the pair sitting on the floor at Saginaw’s house. “We wanted it to be an ‘A’ or a ‘Z’ so it would be easy to find in the phone book. And we picked Zingerman’s.”

In some respects, it’s that same simplicity that has driven a vastly expanded operation since that day some 33 years ago.

Growth came pretty quickly in those early days. And with that growth came what Weinzweig calls “better problems” (the ninth of what he calls “the 12 Natural Laws of Business”—see sidebar).

“Unless you’re standing right next to your employees, they’re not going to do what you want them to do,” says Weinzweig. “It’s not their fault. It’s our fault, because we’re the ones that have to train them. So we had to come up with a teachable format that would work with more and more people in the business.”

Some natural expansions took place — like the 700-square-foot wedge-shaped addition to the 1902 building that took place in 1986 and the purchase of what is now “Zingerman’s Next Door” in 1991, plus a bunch of “little shops” that seemed to pop up throughout the original building.

Then one summer day in 1993, the pair sat down to ask one of those “very important questions” that you can’t help but remember: “Where do you want to be in 10 years?”

Then one summer day in 1993, the pair sat down to ask one of those “very important questions” that you can’t help but remember: “Where do you want to be in 10 years?”

“I didn’t have an answer to that question,” recalls Weinzweig. “But it started a year-long conversation that ended up with our vision written for what we could see 15 years into the future, which would take us to the year 2009.”

Perhaps surprisingly, or maybe not so much, about 90 percent of what was in that document actually came to be, says Weinzweig today.

“We knew we wanted Zingerman’s to be a deli, and we didn’t want a chain,” he says. “It’s not that we’re ethically against it, we just didn’t want to own one.”

What the question was really meant to answer was what kind of growth did they want to see in the space they had.

That evolved into the Zingerman’s Community of Businesses, a network of enterprises (all food based), each of which is run by on-site managing partners who would drive the greatness of the individual business, all of them in and around Ann Arbor.

Today, the privately held Zingerman’s has about 700 employees and about $55 million in total annual sales from nine separate legal entities.

“They’re kind of messed up and kind of going well,” says Weinzweig, in his typical fashion. “Some do better in some years, they’ve all lost money in one or two years, but we’re in the food business where if you have 3 to 6 percent profit, you’re doing great.”

Opening and teaching ‘the books’

This may be a good point in the story to talk about Open Book Finance, which Zingerman’s actively practices (and teaches as part of its ZingTrain curriculum).

“We involve everyone in the business,” says Weinzweig. “In order to do that, they have to see the numbers. They don’t care about statements, but when they’re running the business they need to know sales, cash and understand how the cash turns into profit. It’s something the public has almost no understanding of, but it changes everything when we practice it because now they understand how it works. And they need to know what’s going on.”

Weinzweig uses a basketball metaphor when he’s teaching Open Book Finance at ZingTrain.

“When there’s 21 seconds left on the clock, it defines how quickly or slowly you go up the court. The coaches and the players know, but the average employee in a business doesn’t know what those 21 seconds are in a particular business.”

What’s beginning to be clear is that money, while an essential component of success (natural law 3—without good finance, you fail), isn’t everything when it comes to the success of Zingerman’s.

No, the success comes, it would seem, from getting the right things in the right order.

“If you believe employees are a pain, that customers can become a drag, it becomes self-fulfilling,” says Weinzweig. “And if you don’t work as hard at making the organization itself great, it wasn’t going to matter how good the sandwich was. We’d be dead, crazy broke and in a fight.”

That very idea of good training being critical ultimately lead to the 1994 launch of ZingTrain, a consulting company specializing in training, service, merchandising, specialty foods and staff management. Managed by Maggie Bayless, who Saginaw and Weinzweig met while at Maude’s, ZingTrain shares Zingerman’s expertise with companies and individuals through two-day seminars (typically $1,300 to $1,500 each), workshops (about $300 each) and one-on-one consulting.

Weinzweig says the importance of ZingTrain as a vehicle for Zingerman’s becoming as great as it is today would be hard to overestimate.

“We put a lot of work into creating and building a great organization and ZingTrain ended up doing a lot of that, which, thanks to Maggie’s passion and expertise, elevated the quality of the training,” says Weinzweig. “Embracing learning how to run an organization was critical to our work. It was a big piece of it.”

And being better at what you do takes energy.

“You can learn anything but you have to work at it,” says Weinzweig. “Otherwise, it’s like hiring a nanny to raise your kids.”

Another interesting piece of the Zingerman’s story is that neither Saginaw nor Weinzweig grew up in a family where food was particularly distinctive.

“But everyone likes eating,” says Saginaw. “And here we were, in the food industry, realizing that we really liked it. Ari was a history major and there’s a lot of interesting history in food. I liked the hospitality end of it, mostly because you’re dealing with people when they’re mostly in a celebratory mood. They’re happy for the most part.”

The Zingerman’s journey is one where growth largely defined how systems and people would operate when the work became too big to continue doing things the way they’d always been done.

“The partners we have (in the Zingerman’s Community of Businesses) are much more highly skilled than we are,” says Saginaw. “And we don’t manage any of the businesses.”

The relationship Saginaw and Weinzweig have seems almost magical in how each has gravitated toward their natural strengths and likes.

Saginaw, for example, is a family man who doesn’t like to travel, so he handles bank relations, the legal aspects, the physical stores and operations. “A lot of my time is spent helping partners communicate with each other.”

Weinzweig is perhaps a little more cautious while Saginaw is not. “I think I’m the risk taker,” he says.

And Weinzweig seems to be more the public face of Zingerman’s in that he’s more comfortable with speaking and presenting in a classroom setting.

Saginaw, on the other hand, says ZingTrain is something he doesn’t enjoy. “I’d rather work with the staff. I guess it’s because I never liked school or the classroom and it’s not something I’ve been drawn to.”

Sharing values and a vision

The truth is that the “getting together” story of how the two came to begin Zingerman’s is really something that almost transcends what a business student or marketing professional is likely to instantly grasp.

“For whatever reason, Ari and I found ourselves together in the universe,” says Saginaw. “Although we’re very different in many ways, in some very important ways we’re in line. We have a shared vision; we have a shared set of guiding principles. And we both subscribe to the notion that there is such a thing as ‘having enough.’”

It’s a concept that’s very liberating, says Saginaw.

“It gives you an extraordinary freedom to be generous; to be able to create something extraordinary. Everybody would like the financial noose around their necks to be a little looser, so you’re not worrying about your next house payment or where you’re going to sleep at tonight.”

Saginaw talks about the contrast of wealth when talking about those who have those basic needs already met.

“Having an enormous amount of money is not going to bring joy to your life,” he says. “You may think so, but it’s not.”

On the other hand, for someone who is truly struggling to make ends meet, money does make a difference.

“We can be comfortable that we’re making a little less money,” says Saginaw. “We have modest salaries. But in many, many ways we’re extremely rich and we’re doing work that gives us joy every day. We have more fun now, 33 years later, than we did the day we opened.”

That “enough is enough” is key to the enduring equation that is Zingerman’s. And perhaps your own.

“If you believe you have enough, then you can live this wonderful life,” says Saginaw. “You can be kind and generous, allow people to pursue their dreams and be of great service to your employees and customers and the community.”