The image of a device-obsessed, conversation-averse millennial can make some in the over-35 crowd wax indignant. That 20-something colleague with eyes cast down, fingers cradling phone, thumbs whirling across its screen can make older workers lament what seems to be a dying art: good, old-fashioned talking.

The image of a device-obsessed, conversation-averse millennial can make some in the over-35 crowd wax indignant. That 20-something colleague with eyes cast down, fingers cradling phone, thumbs whirling across its screen can make older workers lament what seems to be a dying art: good, old-fashioned talking.

But older generations are losing the moral high ground, if they were ever up there at all. Parents and grandparents are texting, posting, surfing and tweeting. The Pew Research Center estimates that 85 percent of American adults are online. Smartphone ownership is over 80 percent for people ages 30-49 and at nearly 60 percent for people ages 50-64. If these older adults had access to Tumblr and Snapchat in their own youth, it is hard to imagine them behaving any differently than today’s millennials.

In spite of themselves, older generations are following young people into a new era of communications, one with new habits heavily reliant on typing instead of talking. Today, many people text before calling; email instead of meeting; and ignore voicemail altogether. But technology may not be the only reason people of all ages seem to be talking less.

There is evidence that suggests that employees have long-struggled with the art of conversation.

Mobile phones and computers provide a long-sought-after cover from the awkwardness of conversing. Long before the buzz and ding of app notifications began interrupting meetings, human behavior and business culture were stifling conversation.

Impressions still matter

Whether the issue is an annoying co-worker, a suggestion to improve a business process, or a question about the current project, people tend to consider how their words will be judged by others. Overcoming the near-innate impulse to avoid embarrassment or social consequences is so challenging that doing so has been described by some people as courageous.

To avoid looking “ignorant, incompetent, intrusive, or negative,” people stay silent, said Harvard Business School professor Amy Edmondson in her 2014 TEDx talk, referring to a practice known as “impression management.” Most people have been honing this skill since they were children, so, by adulthood, it is “all but second nature,” said Edmondson.

Impression management can be detrimental to organizational success, said Edmondson. Distracted by the fear of how they might be perceived, team members do not bring their entire skillset to bear on the business challenge in front of them.

The result leaves conversation strangled before it is spoken and innovation defused before it is sparked.

“The need to ask questions, seek help, and tolerate mistakes in the face of uncertainty–while team members and other colleagues watch–is probably more prevalent in companies today than in the days in which earlier team studies were conducted,” wrote Edmondson in her study, titled “Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams.”

Jennifer Akoma, vice president of human resources for Airfoil, a public relations and marketing company based in Royal Oak, says the agency exists to help its clients communicate their messages. But at the same time, internal staff may be reluctant to speak-up about their concerns.

In short, when it comes down to it, speaking up in front of one person or 100 is still public speaking and few people enjoy that experience, she says.

In an effort to create a workplace where staff feel comfortable speaking directly and openly, Airfoil’s leadership team has an open-door policy and regularly meets one-on-one with staff, says Akoma. In response to employee feedback, the company has offered coaching on how to have “difficult conversations” and a program called Creative Labs to allow staff “an hour a month to get together and do a fun activity that encourages communication, problem solving, creativity and leadership,” says Akoma.

Despite these efforts, and an unwritten policy to resolve conflict in person, staff are taking longer to move disputes from email volleys to in-person dialogues. Some staff simply withhold issues until they can speak anonymously, she adds.

Even within organizations like Airfoil that value communication and engagement, these challenges are not unique. Collaboration consultant James Tyer was hired by one company to work with a tightly-knit team suffering from low morale. He had each team member create their own timeline of critical moments, the team’s highs and lows from the perspective of individual members. After about two hours, it became clear that each team member was grappling with the same difficult customer. However, until then, none of them wanted to openly discuss it for fear of hurting each other’s feelings.

Success or failure depends on key conversations

In his TED Talk on the importance of conversation in business, John O’Leary underscored the importance communication plays. “The quality of our conversations influences the quality of our decisions, and the quality of our decisions dictates the quality of our outcomes,” he said.

The co-author of “If We Can Put a Man on the Moon” with William D. Eggers, O’Leary sought to analyze how large government projects get accomplished. One of their key findings was that critical conversations determine the success or failure of such projects. Despite this cornerstone role, businesses, he writes, do not take conversations very seriously. That failure often means the difference between employees speaking up or keeping quiet.

For workers to feel safe enough to risk disagreeing, pushing an issue, or offering an alternative perspective without fear of social consequences or professional retribution, they need “psychological safety,” a term coined by Harvard’s Edmondson. In other words, workers need trust.

Julia Rozovsky, People Analytics manager at Google, led a research team at the firm to evaluate what makes some teams effective and others less so. They found that psychological safety was the most important asset of effective teams. “Individuals on teams with higher psychological safety are less likely to leave Google, they’re more likely to harness the power of diverse ideas from their teammates, they bring in more revenue, and they’re rated as effective twice as often by executives,” wrote Rozovsky in “re:Work,” a website (rework.withgoogle.com) that serves as “a curated platform of practices, research, and ideas from Google and others.”

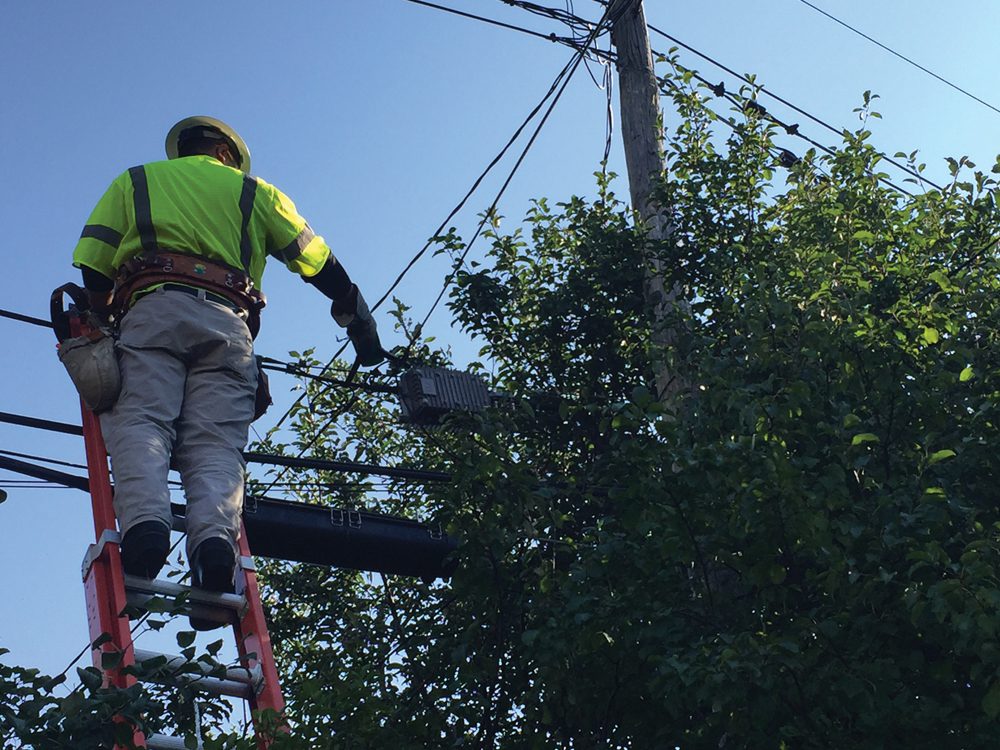

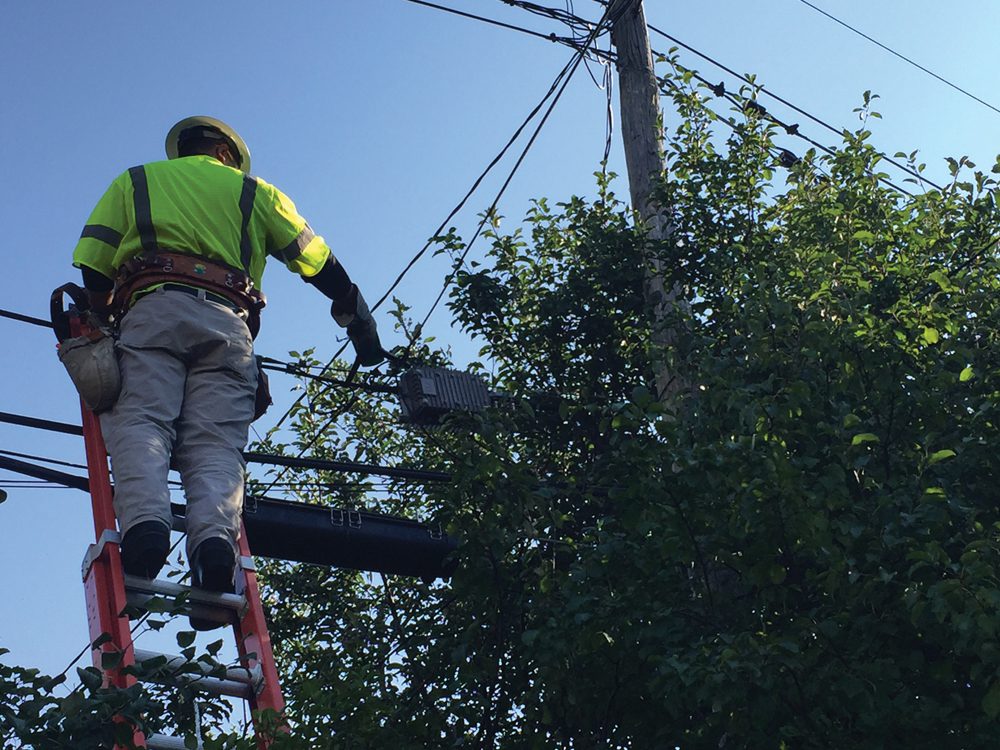

For Comcast’s Jordan Beauchamp, the psychological safety he feels with his co-workers grew out of personal and professional experiences. He and his fellow technicians collaborate on job problems, sharing best practices learned through success and failure. In between work chatter and meetings, they exchange personal snippets, thoughts on last night’s football game, a child’s upcoming birthday, and “some of the personal stuff that we need to get off our chests,” he says.

At work, those conversations are “left unfinished,” so they follow up with each other outside of work. The conversations and shared experiences nurture the sense of “brotherhood” that he has with his co-workers, he says. This mixture of personal and professional communication builds trust between employees, which in turn, stimulates more conversations.

Company values can drive quality communication

Company values can drive quality communication

Building trust may seem like something that happens by accident between people who just “click,” rather than something an organization could deliberately grow. But experts like Edmondson suggest the key to developing trust is in the company’s values.

Edmondson advises leadership to model the values of learning, fallibility, interdependence, and curiosity. “Frame the work as a learning problem, not an execution problem,” she says. “Recognize, make explicit, that there is enormous uncertainty ahead and enormous interdependence.”

Leadership should make it clear that they do not have all the answers and that they could miss critical information if staff do not speak up. “Ask a lot of questions. That actually creates a necessity for voice,” Edmondson adds.

Her advice may seem simple enough, but changing organizational culture can be daunting. Peter John McFarlane, a senior manager in the Analytics & Information Management practice at Deloitte in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, recommends starting small, with a few people. Get those people working as a team, and use them to seed other teams, and so on, slowly branching out. McFarlane contends that teams with psychological safety can be “manufactured.” While working at a previous employer, Habanero Consulting Group, and earning his master’s in leadership studies, McFarlane tested this idea.

In 2013, he and James Tyer (the collaboration consultant mentioned earlier) worked with several Habanero employees, dividing them into three teams. McFarlane and Tyer, whose practice is Togetherwise, used a series of exercises and trainings to teach the teams the importance of norms and to guide them through a series of trust building exercises. Then, the teams were tasked with a real-world work challenge and judged on their performance.

The project lasted about nine weeks and led to several conclusions, one of the most critical being the value of getting to know fellow teammates.

In one exercise, McFarlane and Tyer had the volunteers pair off. In those groups of two, they were tasked with sharing something about themselves. After returning to the larger group, the pairs introduced each other by sharing what they had just been told. Those people who made themselves vulnerable, sharing something truly personal, fared better. “It just takes one person, then they fall like dominoes,” says McFarlane.

Establishing that trust was not a one-time exercise, though. It was something that had to be continually nurtured through team norms, the behaviors that help teams live their values, McFarlane says. So, a norm could be “arrive to meetings on time,” and the value associated with that norm could be accountability or respect. The norms provide a common set of expected behaviors within which the team operates, he says.

Being “open and transparent” at work would seem to run contrary to typical business culture, says McFarlane. “It puts you out there.” But, the benefits are worth the risk, he adds. “Once you trust, you can have conversations with conflict.”

Can technology be trusted?

Remote work is gaining in popularity and, with it, workers are using digital communication platforms to meet, collaborate, and talk. While Facebook and LinkedIn may be effective networking and collaboration platforms, they, along with texting and email, can also serve as impression management tools for the digital age.

Many people use social media and texting to present their “perfect selves,” strategizing each word in a message and posting only their proudest achievements and most flattering photos. “Human relationships are rich; they’re messy and demanding. We have learned the habit of cleaning them up with technology,” wrote New York Times contributor Sherry Turkle, author of “Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age” and “Alone Together,” both about ways technology is changing communication habits.

Can colleagues genuinely bond when a screen is between them? Beauchamp, the Comcast technician who feels he is part of a brotherhood, spends a good portion of his day high atop a ladder and driving to job sites. Texting, email, and apps like Slack and FaceTime are his line to his co-workers. And while he values his group’s weekly in-person meetings, if they were wiped off the calendar tomorrow, he could live without them. But his digital communication channels are imperative, he says.

At TeamSnap, where 75 percent of the workforce is remote, they have managed to create trust among co-workers – even though the full staff meet in-person only twice a year – says CEO/founder Dave Dupont. Employees use apps like Slack and Zoom, as well as email, but also hold regular meetings via video conferencing. Still, Dupont says it’s not the technology that determines the strength of the team, but the people. TeamSnap’s leadership has “a strong sense of the characteristics of good fit with the company,” Dupont said.

In discussing his research, McFarlane makes the point that team building must be “deliberate.” The people leading the project must “believe” in the process. Team members must be selected thoughtfully; they should be the “change makers” within the organization, he adds.

At Airfoil, Akoma may be one of those change makers. Dedicated to getting “Airfoilers” to speak-up, she is meeting them in their comfort zones—an anonymous survey or an email chain. But, from their safe spaces, staff are also able to change the communication habits in their workplace. On one of the annual employee surveys, an Airfoiler requested more team bonding opportunities and interactions between senior and junior staff, the very kind of interactions that help create psychological safety.

In response, Akoma and Airfoil’s leadership began hosting a pet-friendly Halloween party and a Thanksgiving meal where staff shared why they are grateful for each other, says Akoma, the kind of call and response that supports the development of trust. The survey gives employees a safe platform for talking. When they do, Airfoil responds with action. Perhaps pets and gratitude can carry the conversation from there.