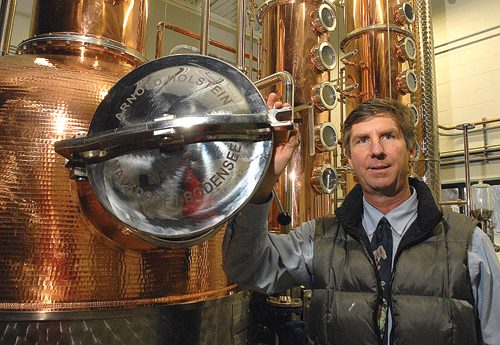

In 2001, Kent Rabish, a pharmaceutical rep from Traverse City, Mich., took a vacation with his wife to Bend, Ore., – and his first micro-distilled vodka tasting became a life-changer. Rabish was amazed at the quality of a locally made craft distilling business and his reaction was, “I came back to Michigan, I was thinking, how could we do this here?”

During the next four to five years Rabish continued his day job while researching the micro-distillery process and business operations through the American Distilling Institute (ADI). In 2007 he founded Grand Traverse Distillery, one of the first 30 micro-distilleries to open in the country. The company started by producing vodka using locally sourced rye grain from a farm 30 miles away, and gradually expanded its bar menu to whiskey, bourbon and gin.

Rabish also extended his role to serve as a guiding principal for distilleries in Michigan. Now, as vice president of the newly formed Michigan Craft Distillers Association, Rabish helps new member businesses with their marketing.

Michigan’s craft distilling industry is growing rapidly behind California, Oregon and Washington state, and non-profit organizations such as the association help bring a voice for the industry on legislative issues that affect the overall beverage industry.

Diana Stampfler, executive director of the association, said the state’s craft distilleries have the right spirit (pun intended) for moving the industry forward. “It’s been a time-consuming process and although no formal organization was in place, the distilleries have been communicating and working together to develop and enhance their industry.”

As recently as 2013, the U.S. craft distilling market had some 425 in-production craft distillers in 47 states, nearly quadruple the 109 distillers that existed five years earlier. Michael Kinstlick, CEO of Coppersea in West Park, N.Y., which publishes white papers targeted toward industry trends, said most distillers start with white spirits like vodka and gin while making whiskey.

Industry’s New Popularity

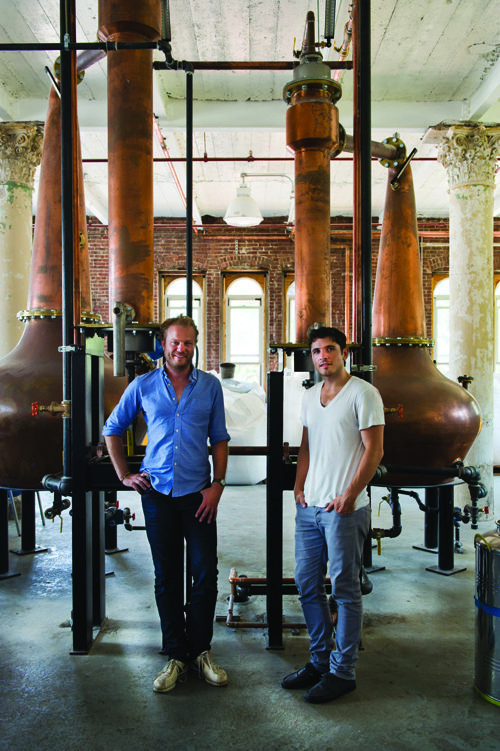

But why is the micro-distilling world on a sudden growth spurt? Colin Spoelman, co-founder of Kings County Distillery in Brooklyn, N.Y., probably has the answer. Spoelman finds this an “exciting time in craft distilled spirits,” where previously the consumer attitude toward hard liquor wasn’t so discriminating.

There is a growing but small number of hard liquor enthusiasts who are thirsty for locally made good quality spirits, he explained. And the liquor industry acknowledges this changing trend experienced by the food and beverage industry, having been through a conscious awakening. The American palate has clearly evolved and it is now demanding exclusivity and authenticity.

Spoelman confirms, “You see it all across the spectrum, as it pertains to coffee, vegetables, there is something about the consolidation of the industry that happened in the last 30 years. And whether that is agriculture or food manufacturing, people are wary of what they are consuming and want to be more responsible and knowledgeable.”

Three years ago, Spoelman founded Kings County and it became the state’s first micro-distillery since prohibition. Among its products: “Moonshine,” a corn whiskey made from 80 percent corn and 20 percent Scottish malted barley and bourbon.

It also makes chocolate whiskey, an un-aged spirit that is infused with the husks of the cacao bean plant, supplied from a nearby chocolate factory. Spoelman says this unusual flavor brings contradicting reactions, with most people expecting to like it, not caring for it. Others, seemingly ambiguous at first, take a liking to the taste.

Kings County’s Moonshine is its top seller and Spoelman accounts that to New York’s unfamiliarity with it, fueling more curiosity. The main draw for the crowd is experiencing an adventurous culinary culture and investigating the truth behind moonshine. And the proof is in the distilled pot. ADI, which has been judging craft spirits nationally through its annual Spirit Competition, in 2011 gave Kings County Moonshine its best in category honors. It won a bronze medal in 2012, silver in 2013 and, this year, gold.

But Spoelman has had to battle his share of cultural snobbery toward new brands. He grew up in Kentucky, the world’s largest producer of bourbon, and to call it whiskey or bourbon it seemly had to be made in Kentucky.

In truth, bourbon need only be made in the United States in order to use the label.

“All these new distilleries have proven that whiskey doesn’t have to come from Kentucky,” Spoelman said. “In a way, by sort of upending conventional wisdom, people are forced to confront their own bias. I think that is part of this excitement – it is that breaking down of lots of myths around spirits.”

Where Did It All Begin?

The craft distillery surge started with California as an offshoot of wineries to make brandy with about 15 entrants in the national market. And when the momentum grew, around 2005-2006, the market evolved to include makers experimenting with all kinds of spirits and flavors.

Ironically, it is California, the birthplace of micro-distilling, that remains the most difficult state for a craft business, with state law prohibiting independent spirit distillers from selling directly to retailers and consumers. The wholesale lobby, which pushed for the law’s passage, compromised to the point of allowing micro distillers to have a tasting room, although they cannot sell any products.

Richard Gahagan, a former Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) employee turned regulatory consultant for beverage alcohol, has consulted for many wineries and distillers, including Grand Traverse Distillery. He points out the challenges in California are because of a three-tier system, the middle-tier being the wholesale level that fights hard to maintain a system that feeds its livelihood.

The Cost of Being Custom Made

The other states have tasting rooms as a marketing tool to sell directly to consumers and retailers. State alcoholic beverage control agencies are enacting laws conducive to the craft distilling business by making licensing fees cheaper and less complex than larger commercial distilling companies. Most states have distilling license fees that range between $100 and $150. The real struggle as an industry is the noticeable tax disparity between winemakers and craft spirits. The Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau taxes distilled spirits $13.50 per proof gallon compared with a mean average of $1.93 per gallon for winemakers. Because a proof gallon is 50 percent alcohol, the tax is adjusted based on a product’s percentage of alcohol.

If you are serious about being America’s next craft distiller (a Food Network show idea in the making), there are few ingredients required to prep for the business. According to Gahagan, the cost to open a micro-distillery varies from state to state, size and equipment costs; in some cases with the scarcity of equipment, distillers end up making their own stills (used for distilling and fermenting the alcohol).

With the business being capital intensive, startup costs can run between $100,000 and $500,000 and Gahagan believes that craft distilleries incur more beginning costs than similar-sized breweries. Spoelman, not revealing his startup costs, estimates an average cost could range between $350,000 and $1 million, including $60,000 for stills.

Here’s something that might motivate future distillery entrepreneurs. Spoelman claims that major players are having trouble keeping up with demand, the reason being they are focused on markets like India and China, and risk losing shelf space in cultural markets like New York, San Francisco and Chicago, where people are more likely to consider craft whiskeys.

It is safe to say that the appeal and growing devotion is here to stay and these small spirit businesses are gaining tourist traction. The buzz is growing and people with refined palates are seeking out tasting rooms to experience distinct flavors these boutique-styled distilleries have to offer. While profitability takes a back seat, imagination seems to be the crucial component in craft distilling. Even with a few hundred players in the market, it is geared to doing “something different.”

Gahagan notes that with a distillery it’s a different type of business. Wineries have grape varieties that make excellent wine and the quality of grapes vary from region to region. “It’s basically the same process and the same product. But with the craft distilling industry, there are jalapenos-flavored vodkas, honey-flavored vodkas, interesting rum and whiskey base products.”

Coppersea’s Kinstlick agrees, saying that with restricted distribution channels, every new player has to bring a unique perspective to the drinking hole. “Five years ago you could open a craft distilling business in Wisconsin and be the first craft distillery and get some attention and buzz and that would give you a good start. But that is no more.”

Different Flavors for Different Players

Even with the market doubling every three years, churning out new micro-players, a business needs to make a compelling case for its product and be able to compete with the Diageos (Smirnoff, Baileys, Johnnie Walker) and Brown-Formans (Jack Daniels, Finlandia) of the world. The competition is spicing up.

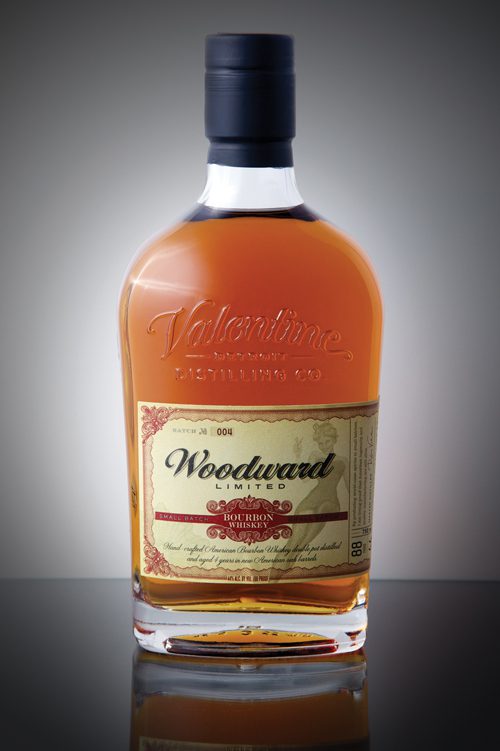

Valentine Distilling Co. in Ferndale, Mich., started in 2007 making their award-winning (gold medal at San Francisco World Spirit Competition) Valentine vodka. It differentiates itself through a proprietary blend of corn, wheat and barley that gives it a creamy, peppery spice and talc finish that is now selling in seven states with hopes to one day becoming a national brand.

The owner/distiller, Rifino Valentine, acting president of Michigan Craft Distillers Association, has a sizable order of his Liberator Old Tom gin being exported to Italy, an offshoot of the product winning the World Gin Awards in London, under the World’s Best Cask Gin category. Although sales have been doubling every year for Valentine’s business, he references an altruistic motive.

The owner/distiller, Rifino Valentine, acting president of Michigan Craft Distillers Association, has a sizable order of his Liberator Old Tom gin being exported to Italy, an offshoot of the product winning the World Gin Awards in London, under the World’s Best Cask Gin category. Although sales have been doubling every year for Valentine’s business, he references an altruistic motive.

“The goal is two-fold, not only to bring manufacturing back, but to bring quality manufacturing back. Some of these awards we won are important to me, not for my ego, but they are important to show it can be done like that. We still do things better here.”

Patriotism aside, this ex-Wall Streeter turned his fascination with the dirty martini into a career by coming up with a locally made distilling business idea on a bar napkin. His next step was hunting for the best vodkas and gin, gathering opinions of bartenders. To his disappointment the answer was the standard mass-produced name brands.

With a staff of a dozen, Valentine has amped up product to maximum capacity. He is reinvesting all his profits in the business, but it took him four years to break even. Valentine feels Portland, Ore., is doing the best job but he wants Michigan to be a leader in the micro-distilling revolution. His long-term plans include having several tasting rooms and giving liquor connoisseurs a reason to relish a locally sourced and manufactured product.

Addressing Portland’s good reputation, Andrew Tice, head distiller and production director in that city’s House Spirits Distillery, reasons, “Portland is such a concentration of creative type people that really want to support local stuff. All the exciting things in alcohol, craft products, they are all happening in Oregon. It’s like the golden age of alcohol production.”

With Wine Enthusiast magazine rating House Spirits’ Aviation American Gin as one of the Top 50 Spirits in the country, the word has been spreading; its gin is now being exported to Australia, Western Europe and select parts of Asia. You can even buy it at the Portland International Airport (after you pass security). House Spirits, founded in 2004, also makes vodka, aquavit, whiskey, and coffee liqueur.

Tice says, “Gin, is a challenge to make something really consistent time after time. To be a great brewer you need to do that all the time. The challenge for a brewer or distiller is you have to make the same flavor (for every batch).”

The distillery takes four years for its whiskey to age, which is made from 100 percent malted barley and fermented with ale yeast matured in two-char American oak barrels.

Aging is a Good Thing

While the mass producers are winning on volume, the small guys emphasize on creativity and authenticity. Makers like Valentine and House Spirits take time to source the right grain, which could be corn, barley, wheat, potatoes or deformed spuds or rye. From there, the search for the right farmer begins, proceeding further to buying or building the processing equipment. As a craft-distilling entrepreneur you begin by registering your business with federal and state governments and start working at the manufacturing facility. But the actual finished product necessitates a long wait – whiskey can take an average of 2-2.5 years to age.

Bill Owens, president of the American Distilling Institute, also addresses whiskey’s popularity. “It has roots, coming from moonshine. It is culturally the most interesting product.”

ADI had its first conference 10 years ago, as a way to help independently owned distillers understand economic development, academic research and education and, in turn, generate more public awareness. The first conference had 68 paid members. This year there are 750, with more growth expected for the future.

Building on its mission, ADI started with trade shows expanding into publishing a magazine under White Mile Press and hosting awards and workshops.

Owens’ opinion on this risky career choice: “It’s something for everybody. Over half of the people have a second job. That really differentiates us from the other industries.”

He also recognizes Washington state as leading the country in the number of micro-distilleries (in-production). The U.S. Craft Distilling Market 2013 study states Washington leads with 53 distilleries, California coming second with 44 and New York as the close third with 43 distilleries. Michigan has about 24.

Washington Knows Best

Washington state is serious about its craft spirits. Distilleries aside, it has 792 wineries and 186 breweries, so it’s safe to say – it’s raining cocktails.

Owens feels, “The reason being, you have a lot of entrepreneurs, Starbucks started there (in Seattle), you have young people educated,” and with the growing number of independent breweries and ample number of bars, Washington is experiencing what he calls a “new cocktail renaissance.”

Jason Parker, owner and master distiller of the year-old Copperworks Distilling in Seattle, echoes the sentiment. “We joke that we really love our liquids here. We make great coffee, we make great drinks, so when it rains, we drink! I think the other reason being there is a good market for it with both food excitement and being out in restaurants with a strong cocktail culture.”

Copperworks, a relatively new player in the market, is producing vodka, gin and all-malt whiskey. Parker earned his place in the professional distilling world by starting as a brewer in Seattle. In 1989, Parker’s former employer was one of the 50 breweries in U.S. and he developed a passion instantly. After graduating college in chemistry and microbiology he went back to small breweries, serving in a variety of roles.

Around 2000, Parker realized the brewing industry was consolidating at a fast pace and it was an “eat or be eaten environment.” After changing careers to IT and working at the Gates Foundation for seven years, a trip to his hometown of Bowling Green, Ky., gave him an opportunity to experience the well-known bourbon trail. At Corsair Distillery he seems to have felt a 23-year flashback.

“While brewing beer we had no idea what we were doing but we were having a blast. It was super creative and we were making up rules as we went along and breaking all the rules that existed up to that point,” says Parker recollecting his feelings about visiting Corsair.

“While brewing beer we had no idea what we were doing but we were having a blast. It was super creative and we were making up rules as we went along and breaking all the rules that existed up to that point,” says Parker recollecting his feelings about visiting Corsair.

Thus another distiller was born. And back in his current city, Seattle, he shared the news among friends that he was quitting his job. While many pegged him an “idiot,” his old friend, Micah Nutt shared his dream and decided to join the distilling scene.

A Quick Pick-Me-Up

“One of the things that drew me back to the community is that it is the best and everybody is creative – bartenders, chefs, all people sharing information. This is the first time I owned a distillery and I am finding that the business community is very excited about distilling. Lots of support from consumers to bankers,” says Parker of his entrepreneurial journey.

Since its inception Copperworks has sold 2,000 cases in a year with 65 percent sales through gin and 35 percent through vodka. For 2014, it expects to sell 1,300 cases of gin and 700 of vodka.

Kings County is currently making 80 barrels a month, which translates to 128 cases monthly. This is an increase from its inception three years ago at 15 barrels a month.

Mass producers like Jack Daniels sell 4 million cases a year in United States alone with Johnny Walker Black selling a million. Although the micro-distillery production limit differs from state to state, according to Kinstlick, the average accepted limit on micro-distilleries is 100,000 proof gallons a year, estimated at about 40,000 cases.

As for generating a successful revenue plan in this independently owned micro-distilling business, Kinstlick declares, “The potential for profitability is there.”