As expected, the Federal Open Market Committee raised the target range for the federal funds rate by three quarters of a percentage point at the July 27 decision to a range of 2.25%-to-2.50%.

In contrast to the June decision, when one FOMC member dissented in favor of a smaller rate hike, the July decision was unanimous. Also as expected, the Fed continues to reduce the size of its balance sheet. In June, they started allowing up to $30 billion per month in maturing Treasuries to roll off their balance sheet, meaning they shrink the money supply as they accept repayment from the government. They are also allowing up to $17.5 billion of maturing mortgage-backed securities (MBS) to roll off per month, and will double both limits in September.

The biggest change in the FOMC’s policy statement was its first sentence, which now reads “Recent indicators of spending and production have softened.” Last month, they said that economic activity was picking up after real GDP contracted in the first quarter, but data released since then have largely disappointed. Housing indicators have turned sharply lower, unemployment insurance claims ticked higher, consumer spending data disappointed, and surveys of businesses and consumers weakened.

Financial markets are also signaling a weaker economic outlook, with the yield curve inverting after the release of the June jobs report, meaning that 10-year Treasury yields are below two-year yields. This is a sign that financial markets see heightened risk of a recession. Chair Powell told the press that slower consumer spending was due to “lower real disposable income and tighter financial conditions,” and the slowing housing market because of higher mortgage rates. Which is to say, the economy is slowing largely due to the Fed tightening monetary policy. The Fed doesn’t want to push the U.S. into a recession, but they do expect “a period of below-trend economic growth and some softening in labor market conditions,” which they see as necessary to bring inflation back to their 2% target.

The Fed’s policy statement was otherwise little changed. They repeated the June statement’s big lines on inflation: “The Committee is highly attentive to inflation risks” and “strongly committed to returning inflation to its 2 percent objective.” Chair Powell repeated statements from June that the Fed is “moving expeditiously” to lower inflation, and that the Fed has “the tools” and “the resolve” needed to make it happen.

The FOMC’s tone has toughened this year as they ended quantitative easing, raised rates, and started shrinking their balance sheet. A year ago, the Fed was still saying that most inflationary pressures would be short-lived, and that inflation would slow by late 2021. They were caught off-sides when inflation broadened in late 2021 and early 2022 to include faster increases of sticky prices, such as shelter and medical services. Then bad went to worse in the spring of 2022, when Russia invaded Ukraine and sent energy and food prices spiraling higher.

Now, the Fed is focused on preventing a repeat of 2021’s mistakes. Chair Powell alluded to this, saying that “supply constraints have been larger and longer lasting than anticipated.” Powell said earlier this year that the FOMC will wait for clear evidence that supply constraints have improved before taking its foot off the brake, since their forecasts of supply-side constraints abating have been so far off the mark. The Fed no longer assumes lessening labor scarcity, shipping delays, lockdowns in China, or chip shortages will help them control inflation—they are prepared to tighten policy enough to slow inflation even if these problems persist.

Even so, the July hike is probably the last three-quarters-of-a-percent hike for a long time. Chair Powell told the press conference, “While another unusually large increase could be appropriate at our next meeting … as the stance of monetary policy tightens further, it likely will become appropriate to slow the pace of increases.”

The Fed made big hikes in the spring and summer to get monetary policy to a neutral stance—meaning neither boosting growth nor slowing it. But rates are now within the range of most economists’ estimates of neutral, and credit-dependent sectors like housing are slowing. In other words, monetary policy is already restraining growth. Future rate hikes will likely be smaller to limit the risk that the Fed overshoots and pushes the U.S. into a recession.

Another reason for the Fed to slow rate hikes is the growing evidence that inflation has peaked. Prices of diesel, gasoline, crude oil, metals, and grains are down from peaks in the second quarter, wage increases are slowing, and housing activity is cooling rapidly, which will slow house price increases. Retailers are warning on earnings calls that their inventories are high, demand is weakening, competition is increasing, and margins are under pressure. That will drive more discounting in the second half of 2022. That’s not enough for the FOMC to stop rate hikes outright; they want to be able to see inflation slow without putting on their glasses. Furthermore, an energy crisis might hit Europe this winter, raising U.S. natural gas and utility bills even higher.

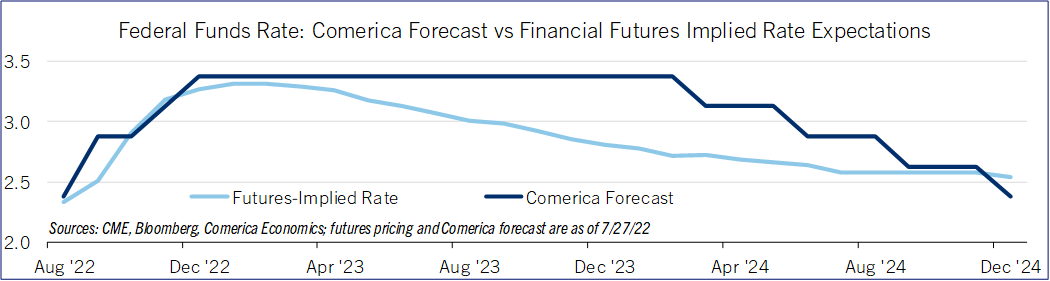

Comerica is holding its forecast for the federal funds rate unchanged after the July decision. The Fed will likely raise the target half a percent at the September decision, and a quarter percent at each of the November and December decisions, then hold the target rate unchanged throughout 2023. Financial markets price in the same peak for the federal funds rate, but expect the Fed to start cutting rates next spring as inflation slows and the economy weakens (See chart).

Long-term interest rates are on a different trajectory. The ten-year Treasury yield and 30-year mortgage rate surged in the first half of 2022 as inflation surprised to the upside and financial markets anticipated the Fed making big rate hikes and shrinking its bond holdings. But despite the Fed’s balance sheet reduction actually beginning in June, longer-term interest rates have been lower over the last month.

Recession fears, a smaller fiscal deficit (the flow of net borrowing, not the stock of debt) and expectations of lower credit demand if the economy weakens further are putting downward pressure on long-term interest rates, offsetting upward pressures from tighter monetary policy. Comerica’s interest rate forecasts anticipate longer-term rates gradually falling through late 2023 as growth and inflation slow and recession fears persist.

Bill Adams is senior vice president and chief economist for Comerica.