The May jobs report sent mixed messages. The survey of employers says the economy is still rapidly adding jobs, but the survey of households says that the long-expected softening of the labor market has begun. The Fed will be relieved to see wage growth slow, and is likely to hold interest rates steady at their next decision.

U.S. employers added 339,000 nonfarm payroll jobs in May, well above the 195,000 consensus forecast; Comerica forecasted a 175,000 gain. May was the 14th consecutive month in which payrolls beat the consensus forecast, and the trend is very strong, with 339,000 jobs added per month over the last year and 283,000 in the last three months. In the latest release, payrolls in March and April were revised up by a combined 93,000, leaving the level of employment in May a whopping 432,000 higher than in the prior month’s report.

By industry, May saw modest job gains in private goods-producing industries, with construction adding 25,000 jobs, but mining and logging up by just 3,000, and manufacturing edging down 2,000. Private service-providing employment rose 257,000, with gains in healthcare and social assistance, up 75,000, leisure and hospitality, up 48,000, transportation and warehousing, up 24,000, and retail, up 12,000. Government employment rose 56,000 in May, mostly at the state and local government level.

Details of the payrolls report were quite a bit softer than the headline. The average workweek shortened to 34.3 hours from 34.4 hours in April and average hourly earnings rose 0.3% from April; this is the shortest average workweek since April 2020. With higher hourly pay but fewer hours worked, average weekly earnings were essentially unchanged on the month (up less than fifty cents).

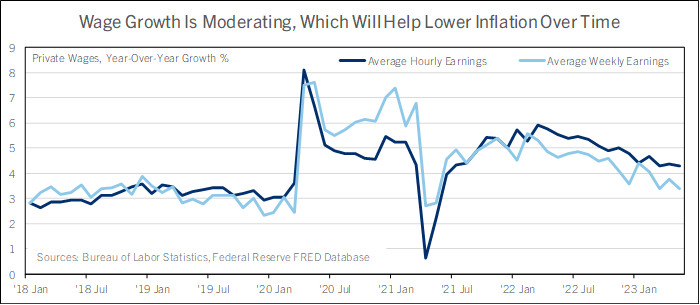

From a year earlier, average hourly earnings rose 4.3%, down a hair from 4.4% in April. Year-ago growth of average weekly earnings slowed to 3.4% from 3.7% and tied March for the slowest increase since May 2021. Also, higher payrolls but a shorter workweek means average hours worked across the private sector rose a modest 0.2% from a month earlier and were down slightly from January. Private sector hours worked rose 1.9% from a year earlier.

The household survey came in much weaker than the payrolls survey, and was also much weaker than the consensus forecast. The unemployment rate rose 0.3 percentage points from April’s 3.4% half-century low to 3.7%, well above the 3.5% consensus (which was also Comerica’s forecast). The higher unemployment rate is a big deal; since the late 1940s, only 4% of months saw larger monthly increases than May 2023.

Employment in the household survey fell 310,000, the labor force rose 130,000, and unemployment increased 440,000. The unemployment rates for adult men and women over the age of 20 rose 0.2 percentage points, to 3.5% and 3.3%, respectively, while unemployment for teenagers 16 to 19 jumped 1.1 percentage points to 10.3%.

The unemployment rate for Black Americans rose 0.9 percentage points to 5.6%; unemployment for White Americans rose 0.2 percentage points to 3.3%; and unemployment among Asian Americans rose 0.1 percentage points to 2.9%. Hispanic or Latino Americans’ unemployment rate fell 0.4 percentage points to 4.0%.

For the Fed, the higher unemployment rate, slowing wage growth, and flat average weekly earnings are persuasive arguments for holding interest rates unchanged at their next decision in mid-June. Strong payrolls growth supports the argument for another hike, but Fed policymakers will likely read it with a grain of salt since the response rate to the survey of employers was very low in May.

At 3.7%, the unemployment rate in May is roughly the same as May 2022’s 3.6%, but other measures of the labor market have cooled to levels near where they sat before the pandemic. In May 2022, payrolls had jumped an average of 579,000 per month in the prior year, and the share of Americans switching employers was near a record high, fueling red-hot wage growth and adding to inflation across the economy.

Now, the share of Americans switching jobs is near pre-pandemic levels, wage growth is moderating, and the Fed’s most reliable economic survey—the Beige Book—shows the economy slowed to a near-standstill in late April and early May. The economy is growing slower than the pace it can sustain over the longer term, opening a small margin of slack capacity and cooling inflation. The money supply contracted over the last year, too, further contributing to slower inflation. That makes the Fed more likely than not to hold their interest rate target steady at a range of 5.00%-to-5.25% at their next decision on June 14. This is likely the peak of this rate hiking cycle. However, risks to this forecast are still to the upside. Fed policymakers are kicking themselves after allowing inflation to surge to a 40-plus year high in 2022 and are determined to avoid repeating the mistake. An upside surprise from inflation (There is a CPI release the day before the Fed’s June decision) or from wages in the months ahead could prompt another increase in the policy rate in the second half of 2023.

Bill Adams is a senior vice president and chief economist at Comerica. Waran Bhahirethan is a vice president and senior economist at Comerica.