As widely expected, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) raised the federal funds target by a quarter percentage point to a range of a quarter to a half of one percent at their March 16 decision. The vote for the hike was 8-1, with St. Louis Fed President James Bullard dissenting in favor of a half percentage point hike. The FOMC’s statement announcing the hike, and the dot plot showing FOMC members’ expectations for the economy, both show members are anxious to tighten policy further. The statement drops language about the pandemic determining the course of the recovery, which had been in policy statements since the pandemic broke out, and substituted in a paragraph about the Russia-Ukraine war. FOMC members see the war as likely to raise U.S. inflation and slow U.S. growth—and their dot plot shows inflation worries them considerably more than growth.

Their statement reads that the FOMC “anticipates that ongoing increases in the target range will be appropriate,” and that they will begin reducing the size of the balance sheet “at a coming meeting.” The Fed’s balance sheet ballooned to $8.9 trillion dollars in March from $4.2 trillion pre-pandemic as they flooded financial markets with dollars. The statement is consistent with the Fed starting to shrink the balance sheet at the next meeting in May.

The dot plot, which summarizes FOMC members’ forecasts for growth and inflation, as well as their views about the appropriate course of monetary policy, shows members expect to raise rates much faster in this cycle than in the last cycle, when the Fed took three years to raise rates from near zero to above 2%. The median of the dot plot (half of FOMC members have higher forecasts, half lower) lowers the projection for real GDP growth in 2022 to 2.8% from 4.0% in the December dot plot, and leaves the 2023 and 2024 forecasts unchanged at 2.2% and 2.0%, respectively. Chair Powell explained the downgraded forecast as largely a reaction to the knock-on effects of the Russia-Ukraine war, which will lower U.S. exports, raise inflation, and erode consumer spending power. The dot plot median sees the unemployment rate falling to 3.5% at the end of 2022 from 3.8% in February, and staying essentially unchanged through 2024, when it would end the year at 3.6%.

The median dot sharply raised its forecast for PCE inflation to 4.3% at the end of 2022 from 2.6% in the December dot plot, and raised the 2023 and 2024 year-end forecasts to 2.7% and 2.3%, respectively. Inflation by the PCE deflator was 5.2% in the latest release for January. The median dot made similar upward revisions to core PCE inflation, seeing it at 4.1% at the end of this year, 2.6% at year-end 2023, and 2.3% at year-end 2024, versus respective forecasts of 2.7%, 2.3%, and 2.1% made in last December’s dot plot.

With the Fed expecting the unemployment rate to settle near the half-century low it reached pre-pandemic, and inflation to overshoot their target for several more years, policy makers are expecting to raise interest rates much faster than in the last expansion. Then, the Fed waited a full year after its first quarter percentage point hike in 2015 to raise the fed funds target again. This time around, the median FOMC member wants to make another six quarter percentage point rate hikes just this year, to a range of 1.75%-to-2.00% by year-end. Last time around, the Fed stopped raising rates in 2018 when the target reached a range of 2.25-to-2.50%. This time around, the median FOMC member sees the Federal Funds rate rising to 2.75% by the end of 2023 and staying there through the end of 2024—but expects that the rate will be back at 2.25-to-2.50% over the longer run. In other words, FOMC members expect to tighten policy into a modestly contractionary stance to bring inflation under control.

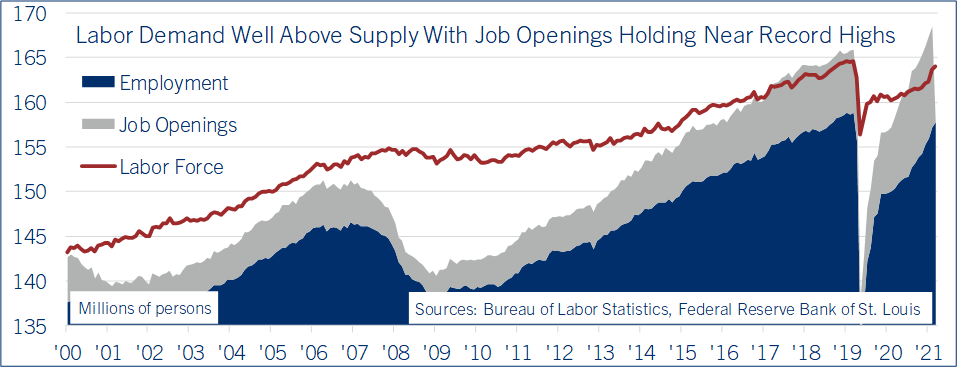

Chair Powell emphasized in the press conference after the Fed’s decision that he sees the U.S. economy as “very strong, and well positioned to withstand tighter monetary policy.” He made repeated references to how labor demand currently exceeds labor supply, which he quantifies by comparing the number of Americans employed plus job openings as a measure of demand, versus the labor force as a measure of supply (See chart). Given Powell’s tone, and information from the dot plot and policy statement, Comerica Economics is revising up our forecast for U.S. interest rates: We now expect the Federal Reserve to make five more quarter percentage point rate hikes in 2022, raising the fed funds target to a range of 1.50%-to-1.75% by the end of this year. We expect one fewer hike than the median FOMC member forecasts because the yield curve is already close to inverting, meaning long-term interest rates like the 10-year Treasury note yield are close to being lower than the yields of two- and three-year Treasury notes. The FOMC is likely to see this as a sign that the U.S. is at risk of a recession, which by late 2022 could make them more cautious about the pace of rate hikes. The Fed will likely make at least two more quarter percentage point rate hikes by mid-2023, raising the federal funds target to a range of 2.00%-to-2.25%. By that time, higher interest rates will have cooled housing demand and slowed home price appreciation. If the Russia-Ukraine war allows oil prices to come down, year-over-year inflation will probably be moving toward the Fed’s 2% target by the second half of 2023, and the Fed could pause rate hikes there.

With interest rates set to rise quickly, the tailwind from fiscal stimulus waning, exports under pressure, and higher oil and food prices hitting household budgets, it is much easier to imagine how another negative shock could push the U.S. into a recession sometime over the next 18 to 24 months. This is why the yield curve is close to inverting. The risk of a recession is probably a one-in-three proposition over that timeframe. More likely, the current expansion will continue albeit at a slower pace, supported by U.S. consumers’ excess savings, recent years’ home equity and stock market gains which bolster household finances, and rising labor force participation as financily-strapped Americans look to supplement incomes.

Bill Adams is senior vice president and chief economist at Comerica.