When we talk about being naive, it’s more often than not with a negative connotation, that somehow the person we’re describing has not considered all the significance of the situation or circumstance they find themselves in or being asked to consider.

And maybe that’s what Veronika Scott was faced with when she took part in a project at a class in design activism created by Stephen Schock, one of her professors at Detroit’s College for Creative Studies.

The assignment was aligned with the school’s redefined mission, which was to help the city with issues of economic and community development.

Scott, a junior at the time (she would graduate in 2011) only had to look around at a community she had come to see as home, perhaps a reflection of what might easily have been in her own family, one that she says had historically struggled with money, dealing with poverty on a most personal level.

“Design to fill a need,” the class assignment said. What Scott saw was a clearly defined need: people sleeping outside of shelters, even when they could have been inside, the reason being issues like privacy, pride or mental health problems were playing a role.

It was part of that design class that got Scott, quite literally, in the business of making coats.

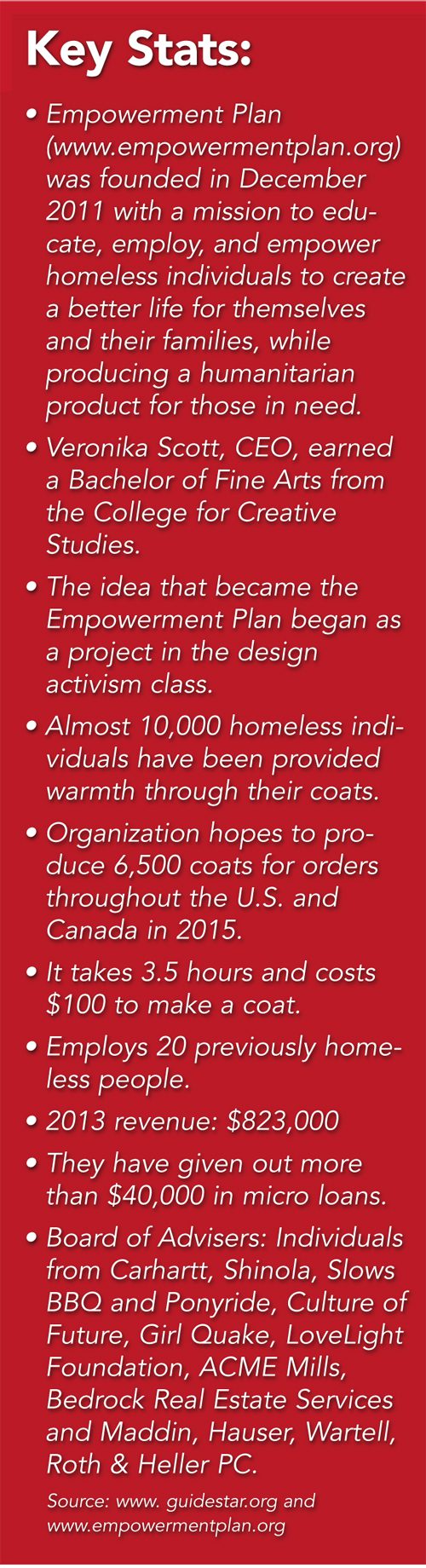

That’s the focus of The Empowerment Plan, a 501(c)3 nonprofit she started a year later, a progression that Scott, who is the organization’s CEO, calls a “long, organic” one that she admits was one that she had virtually no idea of what to do and when.

“As far as the business side was concerned, we really didn’t know what we were trying to do,” she says. “There were a lot of questions, including ones like ‘can I hire someone in the shelter; can I make this coat, this sleeping bag.’ That was all that I was trying to prove, that’s really how it started.”

It turns out, however, that Scott had hit on the essential magic of what is now called The Empowerment Plan, the employment side of a not so complicated, yet highly leveraged equation that is changing the lives of the people with whom she and her team connect.

It turns out, however, that Scott had hit on the essential magic of what is now called The Empowerment Plan, the employment side of a not so complicated, yet highly leveraged equation that is changing the lives of the people with whom she and her team connect.

“The goal is to create these jobs, to help lift people out of poverty,” says Scott, referring to a growing number of people that the Empowerment Plan has hired, people whose lives have, quite literally, been transformed.

One of those was Annis Maxwell, who passed away in 2013.

“She was 58 when she was hired and coming from where she was, she really should have been in prison,” says Scott. “But she was in the shelter, not where she wanted to be when I first hired her.”

When Maxwell started working with The Empowerment Plan it wasn’t long before she became a kind of den mother.

“When she passed away, it hit all of us very hard,” says Scott, who recalls the woman’s son standing up at the funeral and thanking those gathered “for giving us back our mother and grandmother.”

“That’s when I realized the kind of impact we are having at The Empowerment Plan,” recalls Scott.

Indeed, Maxwell had been able to buy a car and a house and she left behind a college fund for her granddaughter.

Since The Empowerment Plan has been operating, some 10,000 coats have been made and distributed through channels in some 29 states and four Canadian provinces.

Yet while the coat itself is obviously key to the enterprise, Scott hasn’t lost sight of the real purpose of The Empowerment Plan; to put people to work.

“If I want to make more and more coats, we’d be set,” she says. “But it’s about having the impact on the employment side that we really believe is the key. It’s about having that impact, thinking, planning, about moving on into something greater and employing those individuals that is really at the heart.”

Creating the coat has been a somewhat iterative process, with Scott and her team paying attention to feedback from actual users throughout its history (one homeless man said an early version “looked like a body bag.”)

One of the latest versions is made of water-, wind- and air-resistant polyethylene on the outer layer, which acts as a barrier, and specialized fabric on the inner layer, which stores body heat. Plus the coat turns into an over-the-shoulder bag with arm sockets acting as additional storage.

A key aspect of The Empowerment Plan “eco-system” is the partnerships Scott and her team have been able to develop with local and national organizations, including Carhartt, which is headquartered in nearby Dearborn, Mich., and which donates fabric for the coat.

In its broadest sense, The Empowerment Plan facility, located on Detroit’s Vermont Street just west of Rosa Parks Boulevard, is a factory, churning out the coats for which it has become famous.

But it’s a keen understanding of the “why” that drives the organization.

And Scott’s thinking.

“The focus is on the humanitarian system to create jobs for those that desire them and coats for those that need them at no cost. The goal is to empower, employ, educate and instill pride. The importance is not with the product but with the people,” she says.

The evolution of purpose

It was back to her college days that the sensitivity to the area’s poor may have first coalesced.

“I had ramen and a roof over my head, so my needs were being met as a college student,” says Scott. “But just walking out the door, you realize there are needs bigger than your own.”

Assignment in hand, she reached out to the homeless (there are 20,000 “counted” Detroiters living on the street, with estimates reaching 36,000), spending three days every week for five months working in a homeless shelter downtown.

In essence, as Scott recalls it, she went to “the worst and the most dangerous homeless shelter in the city of Detroit, at 8 o’clock at night, alone” and asked for help.

“I went in there with the idea of research,” she says. “I showed up on the first day in front of a crowd of 30 people, people who could only keep the belongings they owned on their lap because everything else would be thrown out.

Scott told the group that she was not there to help but to hear from them.

She admits the response was not the greatest but she came back, three times a week, for five months.

When she saw, a few days later, an abandoned playground 20 feet away from the shelter where people were living outdoors under makeshift tarpaulins, the idea for the coat began to coalesce.

“Why would someone risk their lives, why would they risk dying of hypothermia, just to build a house for themselves, when someone was offering it to them for free?” Scott asked herself.

It turns out the answer was the same motivator that we all have. They did it for pride. For independence.

“They’re like everybody else. We’re all the same. We want to take care of ourselves,” she says.

That thinking lead to a realization that still stands today. Scott wasn’t designing a coat just for the tangible need of being cold but because of an emotional need, that being pride.

Scott admits she really didn’t know where to go with the idea.

“I designed the first coat with my mother,” she says. “I learned to sew; it took us 80 hours to complete the first one and it was the worst experience of my life.”

She calls the “product” a 20-pound “Frankenstein” coat/tent made of trash bags and seven wool coats that had one shelter resident come up with the “body bag” comment.

Scott says the value of the experience was that she failed “hard and fast,” eventually coming back with three different versions and earning a nickname for herself — the Crazy Coat Lady — but more importantly a sense of anticipation among the shelter residents.

“People would ask me ‘so, when am I going to get my Crazy Coat?’”

What Scott was thinking (but did not say) was “never.”

“I was also thinking ‘I’m a student; nothing I’m doing is meaningful.’”

But that all began to change, she says.

“I didn’t feel it was over,” she says. “I continued the project not just because I was passionate about it, but because actual people needed, wanted and desired it. I realized I had to take it to the next level and make it a system.”

“I began to ask as many people as I know how I could create a business from this,” she says. “I knew nothing about business and I knew I didn’t know how to sew. I was horrible.”

At first, people were “very generous in telling me the ways I could fail,” says Scott. “I heard a lot about the many ways it was going to crash and burn and how I would get sued.”

What she did do, however, was begin to take notes and put together a “to do” list.

That’s when, as Scott says, “everything changed.”

“I said ‘OK, I have an idea. All I need now is money.’”

Not long after, Scott had the opportunity to meet with Mark Valade, CEO of Carhartt, who asked her what she needed. (Valade later became an adviser.)

Scott chuckles when she tells the story, as she did at a TED Talk in San Jose, Calif., in 2012.

“I had 27 pictures and a teeny spreadsheet at the back saying I needed $1,600 to run this for a year.”

The TED audience laughed as Scott told the story.

“No one laughed at me when I first showed it,” she says. “I wished they had.”

But Valade, the Carhartt executive, “saw something in me that I didn’t see” and within a week, Scott says she had two tons of industrial sewing machines and fabrics “headed to my grandmother’s house.”

In relatively short order she had found space — “a closet really” — in the homeless shelter where The Empowerment Plan had first come together; by December 2010 she had hired her first employee, a 17-year-old. In three months, thanks to donations from the public, Scott was able to fund a full salary for that first hire.

Three months after that, Scott’s first employee had been able to move out of the shelter system entirely, was in an apartment and had all three of her children enrolled in school.

Lives saved and empowered

Today, The Empowerment Plan can produce 1,000 coats on a budget of $100,000.

But the human impact is even more poignant: research now shows that for every 1,000 coats distributed, as many as 14 lives can be saved along with about $58,800 in annual reductions in health care costs.

At a practical level, those statistics deal with the estimated 7 percent of homeless individuals who die from hypothermia. The coat clearly reduces that sobering statistic (with studies showing a 20 percent reduction).

Scott, who earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from her time at CCS, believes The Empowerment Plan is her career going forward.

“I’m not being flippant about it,” she says. “This is something I’ve put a lot into and we’ll see where life takes it. I’m excited about this. From the beginning, this has been my employment, too. It’s where I see my future, trying to create this employment, for myself and for the people who work here as well.”

Scott is also entirely practical in her thinking about the role a non-profit organization like The Empowerment Plan plays in the economy.

“Non-profits are businesses,” says Scott. “They have to function like that because the more you act as a business, the more you can help people. They’re not mutually exclusive concepts. You can do good work while doing good business.”

In the months and years since The Empowerment Plan has taken shape, Scott herself has become more proficient in the telling of the story, having spoken to dozens of media outlets and even taken the stage at six “TED” talks.

In Scott’s case, not being aware of what it took to run a business meant she had to reach out to others who could provide her with the direction she needed to make The Empowerment Plan a success.

She admits, however, that if she had known all that was involved before she began going down this particular road, she might not have started.

Scott had applied to various art schools and even thought of being a lawyer or designer.

What she didn’t want to become was what she calls a “typical” artist. “I always hoped to be able to help myself,” she says.

She chose the College for Creative Studies for the most practical reasons possible.

“They had the most amount of scholarship,” says Scott. “That meant I wouldn’t have student loans, which for me was a very important thing. My grandfather had told me ‘there’s no such thing as good debt’ and I kept that in mind all the way through school.”

In 2010, Scott was invited to the United Nations to speak as a young woman change-maker. In 2011, the Clinton Global Initiative (part of the Clinton Foundation) had her speak on her drive to create The Empowerment Plan. And in 2012, she received the JFK New Frontiers Award from the John F. Kennedy Library Foundation, the youngest to have received the honor.

In perhaps a year, The Empowerment Plan may itself be evolving, possibly opening up a retail network for sales of the coats it makes, quite likely in graduating people into other jobs.

And yes, it’s all about the jobs.

One of the most constructive criticisms Scott received, from a woman she had met in the shelter, a woman who had been homeless for decades, still resonates in her memory.

“She screamed at me when I was walking out one day, ‘Your coat doesn’t matter. Jobs matter. What you do means nothing unless you create jobs.”