Bring up the subject of the future of electricity transmission, not only in Michigan but across the nation, and Linda Blair, CEO of ITC Michigan, the biggest division of the nation’s only independent transmission operator, will inevitably bring up her company’s Thumb Loop project.

For Blair, the $500-million project, a 140-mile, 345 KV line that traces the state’s iconic “digit” and its four new substations, is the kind of good news made possible by a firm of the depth and breadth of ITC.

The project serves as the backbone of a system designed to meet the identified maximum wind energy potential of the area, while being an important link in the high-voltage transmission system in Michigan and the region.

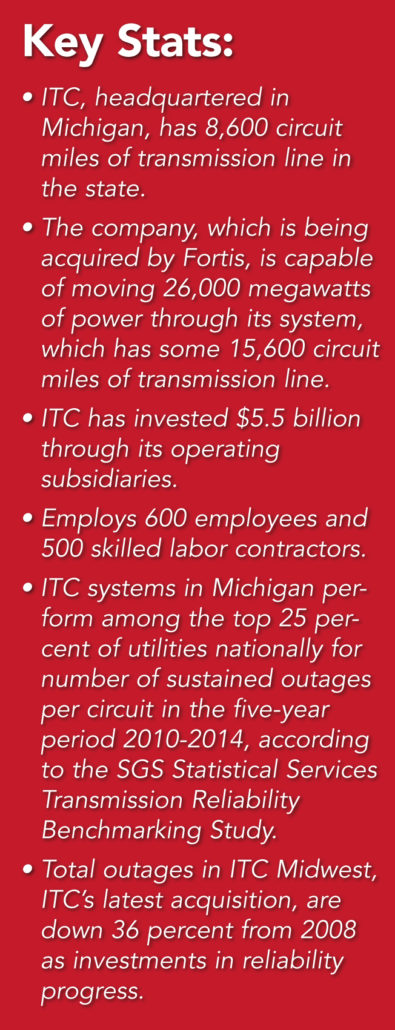

ITC began the project in 2013 and wrapped it up in May 2015, spending about $500 million of the more than $3 billion it has invested in total since the company’s inception in 2003.

From the standpoint of a return on investment to the community, the Thumb Loop project seems to be a winner, with an estimated economic benefit of $350 million in its first year alone, according to Blair.

For a transmission company like ITC, investment is key, not only when it comes to building a broad-based network that will serve its own customers (the utilities that generate the power) but the public at large.

And Blair remains concerned, not that the intentions to grow and renew a national grid structure aren’t pure, but that a new perspective is needed to ensure power gets to where it is most needed—a seemingly obvious quest, but one that can have dramatic impacts (good or bad) on the future of the economy.

The changing energy landscape

“When we think about the investment that is needed as far as transmission infrastructure is concerned, it’s very easy,” she says. “We’re in charge of our identity; we can do anything out there. But when you think about the energy landscape, where it’s going, reducing carbon emissions, shutting down coal and bringing more renewable energy online, dealing with what is going to be a significant, dramatic shift from fossil fuels to renewables is important.”

Blair likens the infrastructure in place across the country, moving electricity from where it’s generated to where it’s needed, to the role of the interstate highway system, the single biggest benefit of which, she says, is the development of commerce.

“The highway system wasn’t done to connect McDonald’s, but those on and off ramps are where manufacturing blossomed and when we think of the next generation of transmission grids, we need to think about where the next generation facilities will be.”

The good news is that as far as renewables are concerned, society already knows where the sun shines and where the wind blows, one of the two key sources of input for clean energy.

“Clean power is going to drive the next wave of generation,” says Blair. “But most states are going to do their own plan, deciding which generation units they’ll retire and which will be brought off line, and what they need to have to supplement their energy needs. The question will be, will those kinds of decisions be done state by state or will there be someone who comes in and works to avoid duplication?”

“Clean power is going to drive the next wave of generation,” says Blair. “But most states are going to do their own plan, deciding which generation units they’ll retire and which will be brought off line, and what they need to have to supplement their energy needs. The question will be, will those kinds of decisions be done state by state or will there be someone who comes in and works to avoid duplication?”

It’s something of a rhetorical question for Blair, who is advocating for a perspective that will, at the very least, take a regional approach to planning in the most efficient way possible how a national transmission grid will come together, one that represents a future that society as a whole will see as beneficial economically and, as far as renewables fit into the picture, ecologically as well.

“We need to design a grid that interconnects where we know the natural resources pockets are to where it naturally makes sense to operate,” says Blair.

She’s boiled it down to a wish list of three big issues that need to be addressed if the future of not just transmission but the entire electrical system—from generator to end user—is to flourish.

The first is having a robust regional planning process, at least in some way that is overseen by an independent authority able to take a “top down” approach (rather than the current “bottom up” process that takes into account only localized needs that may not be consistent with needs just a state or two away).

“This doesn’t mean it’s going to be adversarial, but more ‘big picture,’” says Blair. “It’s not that the old system doesn’t work, because it does for the old system. But it’s not where the country needs to go.”

A second issue relates to the money side of the equation: allocating in a way that recognizes who should pay for the critical investments in things like transmission, which have historically been paid for at the local level.

“If you’re building infrastructure for an entire region, the region should pay for it,” says Blair. “In some cases, there has been progress, but we need to do more. We need to get to the point where people recognize that transmission is for the benefit of all. We have the private equity to do it. It’s a regulated, stable, solid long-term investment.”

The evolution of ITC

How Blair and her colleagues initially got to this point in the discussion around future energy transmission policy is a story worth telling, one that began with an idea.

All ideas have a moment, people who were in the room will tell you, when the initial concept is broached, something that has never been tried or not even considered.

One of those ideas took place in 1999, the year someone at DTE Energy, the $28-billion energy company that serves 2.1 million electricity customers in southeastern Michigan, got the idea that the “moving” part—taking electricity from its generation plants to the factories, businesses and homes throughout its network—might be worth more than a typical vertically integrated utility like DTE might think.

DTE already realized that the transmission part of its business, the network of high-voltage lines that we’re all familiar with (and which at Christmas might be lit up with bright colored lights), was accounting for a relatively miniscule amount of its revenue, an average 4 percent compared with the 60 percent derived from generation and 35 percent from distribution, the utility side of the business.

So here’s the idea: Maybe the transmission part of the business could be worth more as a separate entity, an enterprise that DTE could subsequently turn to for service, but paying for it like they’d pay for anything else.

“We think it’s a part that could be worth more to someone who wants transmission to be a core part of their business, not just a piece,” was the thinking behind those early discussions.

DTE’s transmission specialists, people like Joseph L. Welch, who headed the transmission side of DTE, began exploring what a sale might look like and, more particularly, who might be the purchaser. They set out to do their number crunching, working with consultants and sweating out the details, as they did what any good corporate team member would do to enhance the value of the mother ship.

Now remember, these are people—Welch was dealing with a relatively small team at the time—who have lived and breathed air that was infused with the resources typical to an integrated, highly vertical enterprise like DTE, originally called Detroit Edison (DTE being its stock trading symbol).

If this idea worked, that corporate family connection would be gone. Transmission would be on its own, albeit performing an essential service to its former electrical generation and distribution kin at DTE, but nevertheless outside the nest. It would, in essence, be moving out on its own.

And make no mistake. There was a business here. It was even given a name — International Transmission Co. — as part of DTE’s plan to sell it off. In fact, it was a very good business from the perspective of Welch and his team. So much so that they decided to team up with one of the prospective sources of investment funds, the legendary Kohlberg, Kravis Roberts (KKR), a private capital equity firm with a reputation for leveraged buyouts. This was the company that in 1988 had leveraged a $25-billion buyout of RJR Nabisco, then the biggest of its kind. Much later, in 2007, KKR would go on to do what is still seen as the largest buyout in history, the $44.37-billion acquisition (in partnership with others) of TXU, a Texas utility and power producer, perhaps in a small way a result of KKR having tasted the sweetness of buying DTE’s transmission network.

Just two years later, ITC Holdings Inc., the new corporate entity, would do its own Initial Public Offering, with KKR cashing out its capital and the fledgling transmission company now on the kind of solid financial footing that only people like Linda Blair can truly appreciate, perhaps for what at the time could be considered a precarious situation.

Blair, who was one of the others in that room in 1999, has a background in regulatory and public affairs, and is an executive familiar with dealing with the public, including in her role as manager of transmission policy and business planning.

Today she is executive vice president and chief business unit officer for ITC Holdings Corp., serving as president of ITC Michigan, which includes not only the assets originally carved off by DTE, but also the former transmission assets of Consumers Energy (now METC), which ITC bought from TransElectric in 2006.

“Failure was not an option for us,” she says from a room that overlooks one of ITC’s transformer stations, its towers stretching out beyond what we can see on a bright Friday afternoon. “The reality was that we had no corporate support at the beginning. Everything we did was from the perspective of real-time decisions. We knew we had to live or die by those decisions, but they were made.”

As a publicly traded company, ITC Holdings Inc. has the kind of access—cheaper access to be clear—to the investment capital that it has used to acquire assets like METC, with its 5,600 circuit miles of transmission lines and 36,900 transmission towers and poles.

It has also grown its business in other areas, notably ITC Midwest, a subsidiary established in 2007 when ITC bought Interstate Power and Light and its assets in portions of Iowa, Minnesota, Illinois and Missouri.

ITC is also growing through what’s called a “greenfield” business model, one not predicated on acquiring other systems, which it is doing through ITC Great Plains, a transmission-only utility that became a member of the Southwest Power Pool. ITC Great Plains is itself a subsidiary of ITC Grid Development, which was established in 2006 to explore new investments in the nation’s transmission grid, focusing on partnering with local entities and utilities to improve electric reliability through infrastructure improvements and the creation of a regional transmission grid.

It’s that talk about the “big picture” that includes the country’s ability to move, efficiently, flexibly, and, yes, profitably, the critical energy that will ultimately power everything we do that gets Blair’s attention and is part of her vision of what could truly drive America’s future.

New owners

This might be an interesting time to bring up a development that occurred after Corp! magazine interviewed Blair.

Just days after we talked, Fortis Inc., a Canadian company (it’s based in St. John’s, Newfoundland), announced a $6.9 billion cash-and-stock acquisition of ITC Holdings Corp., citing its tremendous growth potential given the long history of under-investment in the U.S. in both transmission and local distribution assets.

The sale announcement included a nod to President Barack Obama’s Clean Power Plan (which in February was issued a stay by the U.S. Supreme Court, pending judicial review). But however that plays out, energy from renewable sources like wind and solar will still need transmission lines to bring that electricity to market.

Fortis, which is paying a premium of 14 percent to ITC’s closing stock price (Fortis—FTS—trades on the Toronto Stock Exchange), says it will spin off up to 19.9 percent of ITC, which will become a subsidiary of the Canadian company.

Barry Perry, Fortis’ chief executive, says the company has grown its business through strategic acquisitions that have contributed to strong organic growth in the past decade and that buying ITC—”a premium, pure-play transmission utility—is a continuation of this growth strategy. ITC not only further strengthens and diversifies our business, it also accelerates our growth.”

The acquisition, still subject to regulatory approval, is expected to close by the end of 2016.

Transmitting the future

Back to Blair and her last key issue regarding how her goals for a “perfect world” might play out. That one deals with the “where” question as it applies to transmission lines that will link generation to where the power is needed.

“We think states and local municipalities are best positioned to decide on where transmission infrastructure is built,” says Blair. “At the end of the day, we want to do what’s best for the region, but if the state isn’t going to allow [a line] to be approved, we need the next level.”

That would be eminent domain, the U.S. term for the legal authority vested in the government to acquire property deemed to be in the public interest.

Blair says that while there may be somewhat competing agendas in play when it comes to mapping out a future that maximizes the benefit to society and everyone likely to share the prosperity we hope to achieve, a workable solution is possible.

“We need an independent planning authority, a federal group with the ability to design and plan the future transmission grid based on where the wind blows and where the sun shines,” she says, referring to basic facts that drive the development of renewables.

Blair has an answer for those who might suggest renewables are too unreliable and/or inefficient to make a dent in the demand side of the power equation, an important thought, if for no other reason than the Thumb Loop project ITC invested in targets the generation of power through wind turbines.

“There have been massive efficiency gains when it comes to wind turbine technology,” says Blair. “What used to be (efficiency) factors in the 35 percent range is now 50-60 percent, which is nearing what existing coal plants are able to achieve.”

And yes, the wind sometimes doesn’t blow at all, but Blair points out that when it does, ITC sees as much as 1,400 megawatts of power produced, which means fewer tons of coal and fewer rods being used for fuel in a nuclear plant.

Even with traditional, fossil-based fuels like natural gas, which Blair calls the “fuel du jour” due to its low cost, the information needed to create a forward thinking transmission strategy, one that makes sense from a national perspective, is something that’s well known.

“We know where all the gas fields are and we know where the existing pipelines are. We know all that,” says Blair.

ITC, alone or as part of a conglomerate like Fortis, will surely continue to reap the benefits of a transmission grid that is modern, flexible and robust enough to do what we all want it to do, all while ensuring investors and consumers (who are the ones who ultimately pay the bills) benefit.

And that means a continuing need to invest in transmission infrastructure.

“When you think about how high tech businesses are today, with the growing demand for energy, it’s something that has doubled since the 1970s,” says Blair. “During that time, we’ve seen no major change or upgrading of the transmission grid, aside from the kind of investment that we’ve made.”

Editor’s note: This is the first in a series looking at Michigan’s infrastructure and the individuals and businesses that play a part in it.