The news media report often on the demise of retail stores, citing the shrinkage and even closing of chain stores and malls due to competition from big box discounters and online sales.

But the reality is more complex and less glum for retailers.

“We’ve all heard that retail is in trouble – even serious trouble, depending on who you listen to,” says Mark Matthews, vice president/research, National Retail Federation (NRF). “It’s true that some large, well-known brands are facing challenging times, just as in every industry. But the narrative that retail is struggling – or even dying – is significantly overblown.”

To compete successfully today, NRF experts say retailers must adopt new technology and invest capital into creating multichannel customer experiences. That may mean an online presence—a website offering online sales along with social media to nurture a customer base.

But brick and mortar stores are by no means obsolete. Global management consulting firm A. T. Kearney, in its 2014 Omnichannel Shopping Preferences Study, said 90 percent of shoppers “engage the physical store somewhere along the shopping journey.”

The reality is that the in-person shopping experience is still a major force in generating sales and loyal customers. And that experience varies tremendously depending on the type and location of retail outlet—from a locally owned pop-up, a brick and mortar store in an urban or suburban downtown, or a chain store in a strip mall or enclosed mall.

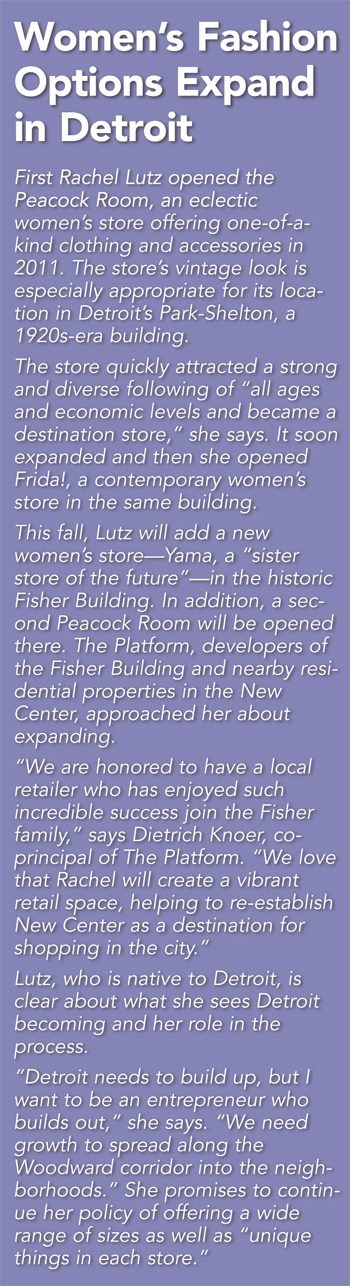

Retailer Rachel Lutz, who owns The Peacock Room and Frida! women’s clothing stores in Midtown Detroit, Michigan’s Park-Shelton, believes that city stores like hers provide a unique experience.

“Urban stores are real. They’re authentic,” Lutz says, comparing her style of store to the ones she formerly worked at in The Somerset Collection in Troy, Michigan. “There are not many family-owned stores (there), so you don’t know the customer well.”

Personally knowing and serving the customer well are important qualities for creating a successful shopping experience, Lutz believes, and retail experts agree. “Fashion is very regional and I’m selling them what they want, but introducing them to new things,” she says.

Personally knowing and serving the customer well are important qualities for creating a successful shopping experience, Lutz believes, and retail experts agree. “Fashion is very regional and I’m selling them what they want, but introducing them to new things,” she says.

However, urban retail is not only about the merchandise and experience within a store. Ideally, it is integrated within a downtown area or city neighborhood. “You go to the store, a new restaurant, an art exhibit. Cities are denser and have walkability. They tie together places where people, live, play and work,” says Lutz. While some of her customers live or work in Midtown, many are destination shoppers seeking out her store.

In downtown Detroit, Dan Gilbert and his company’s real estate arm, Rock Ventures, has purchased more than 90 buildings and is transforming some into retail space. Downtown workers, including 15,000 employees of his related companies, provide a natural market for new stores, but housing being developed in and near downtown will provide additional potential shoppers.

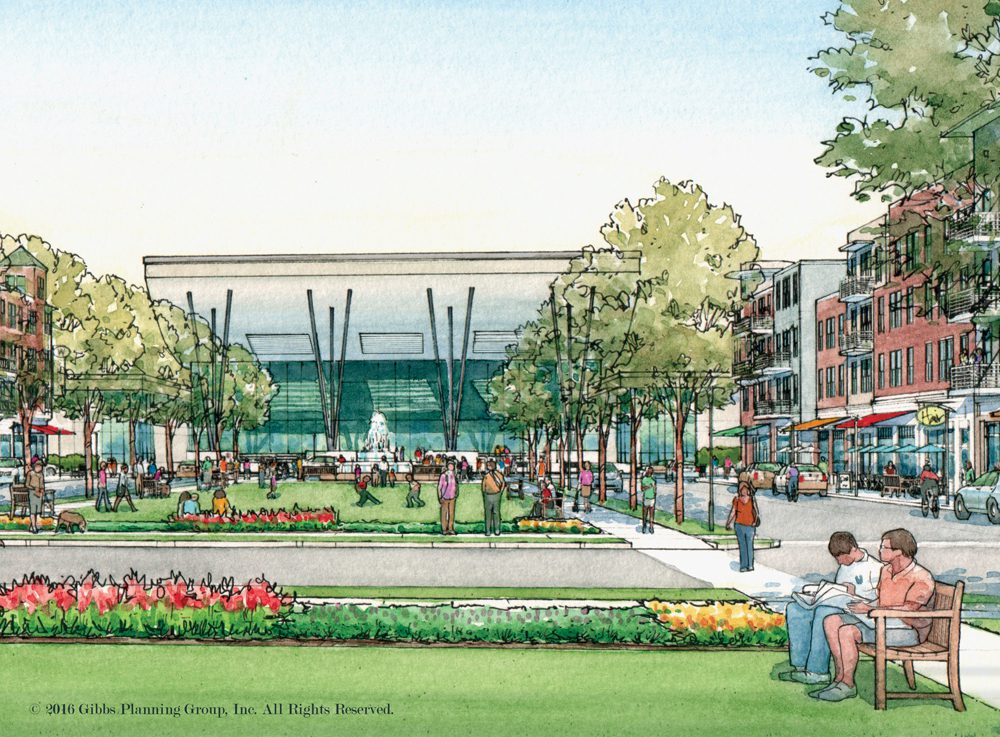

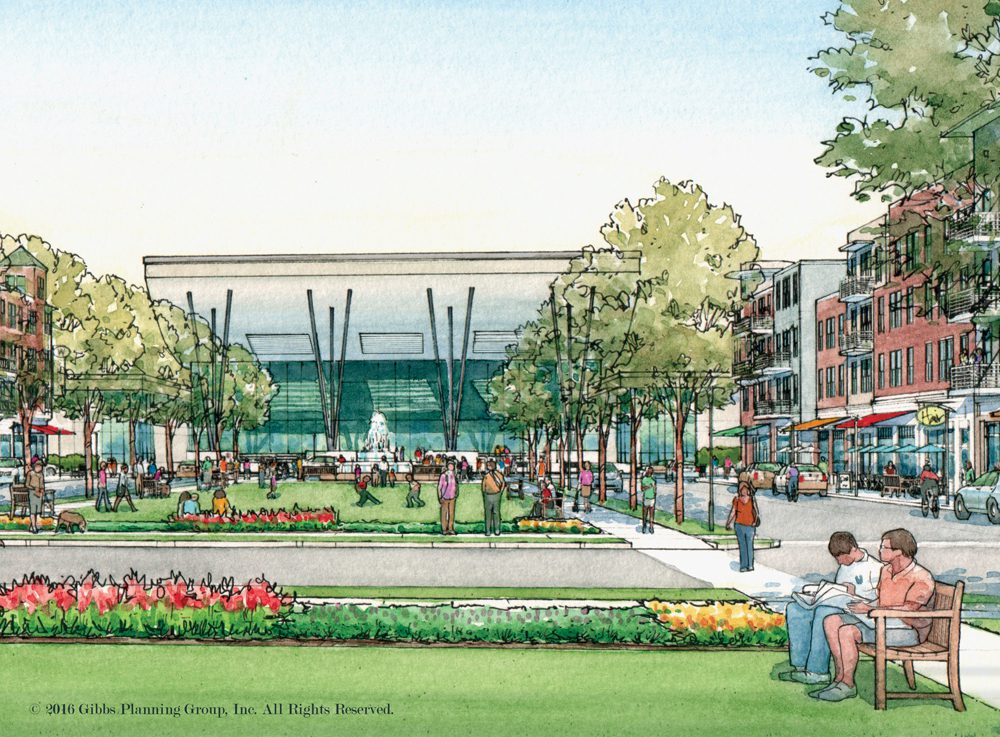

Up until the Depression, cities were designed on an urban pattern with residential, employment, civic, and retail development enmeshed in one large space, says Robert Gibbs, president of Gibbs Planning Group, Inc., based in Birmingham. Gibbs is an internationally-known urban planner who works with cities and suburbs to create compact, walkable mixed-used developments. He developed Birmingham, Michigan’s retail plan and is a consultant for the City of Troy, which is planning a large-scale mixed-use development encompassing its civic buildings.

After the Depression, Gibbs says, the “sprawl model” went into effect, with shopping, office and residential areas separated and reachable mainly by car. Now, he says, suburbs such as Troy are concerned about the sustainability of this kind of development. Empty nesters are interested in condos in areas where they can walk to a store or restaurant. Suburban downtowns like Birmingham and Plymouth, Michigan, as well as planned mixed-use developments in other areas, attract visitors “because they can do more than just shop,” Gibbs explains. Also, there is usually less time required to park and reach a desired location in a downtown or mixed-use development, compared to a large shopping mall, he claims.

After the Depression, Gibbs says, the “sprawl model” went into effect, with shopping, office and residential areas separated and reachable mainly by car. Now, he says, suburbs such as Troy are concerned about the sustainability of this kind of development. Empty nesters are interested in condos in areas where they can walk to a store or restaurant. Suburban downtowns like Birmingham and Plymouth, Michigan, as well as planned mixed-use developments in other areas, attract visitors “because they can do more than just shop,” Gibbs explains. Also, there is usually less time required to park and reach a desired location in a downtown or mixed-use development, compared to a large shopping mall, he claims.

Urban locations with nearby public transportation can enhance store access. Lutz says that Detroit’s Q Line, which has a stop close to the Park-Shelton, has increased pedestrian traffic and had a positive impact on sales.

The Fisher Building is the first stop on the Q Line at Woodward and Grand Boulevard. Dietrich Knoer, co-principal of The Platform, a leading New Center development firm which owns the Fisher Building, thinks that the streetcar line will make the building more accessible and bring others to the district.

While parking is often cited as an impediment or at least an extra cost to urban development, Knoer points out that the New Center offers a range of options from street parking to $5 surface lots to more expensive secured lots and structures. He also mentions “alternative transport,” such as bike sharing, as a positive option for visitors.

Knoer points out that retail is far from new to the Fisher Building, a national historic landmark, since it was built with a three-story enclosed retail arcade connected by elevators and stairs. The Platform’s initial retail focus is the ground floor and maybe some stores on the concourse level.

Some of the Fisher Building’s retail tenants—including Russell Pharmacy and the Contemporary Gallery of Arts and Crafts—have operated in their locations for decades. “We have a great tenant base and the building is about 70 percent occupied,” Knoer says.

In filling the remainder of the retail space, Knoer says the goal is to be a destination with a good mix of national and local stores, although they are not really seeking big national brands. Their focus is local proprietors on a small scale, who will provide service to the community—both the daytime population of 10,000-15,000 office workers and the New Center neighborhood. In addition, during the theater season as many as 2,000 individuals attend a single performance at the Fisher Theater.

The Platform is in the construction phase for 230 apartments near the Fisher Building and plans other residential development. Knoer notes that some apartment buildings in the area are being remodeled. He anticipates that his customer base will look quite different in several years.

In addition to the Peacock Room and Yama, The City Bakery, a New York and Japan-based chain, will open this fall in the Fisher Building. The Detroit location will be their first outside of New York City and Japan.