The Detroit office of C/D/H, in the Wright-Kay Building, officially has 15 employees, plus-one, simply known as Dash.

This one-named-wonder doesn’t know the first thing about developing innovative software solutions, which is C/D/H’s specialty. Instead, Dash is learning how to save lives.

The 10-month-old female Goldendoodle, (Golden Retriever and Standard Poodle) is undergoing rigorous training to become a diabetic alert dog by 2017 that will allow her to detect if the glucose levels of owner Shannon Inglis, C/D/H marketing coordinator, dangerously fluctuate.

A type 1 diabetic, Inglis is thankful that her employer not only welcomes Dash’s presence in the office but also understands that once fully trained, she will provide Inglis with peace of mind.

“It will be a weight lifted off my shoulders,” says Inglis. “I will be able to work without the extra worry of my health. I can safely go about my day without having to worry what my blood sugar may be doing at any given time.”

A service dog like Dash can mean independence, employment and financial stability for many of those with either a visible or invisible disability.

In America, there are 56 million people (1 in 5) with disabilities, according to a report by the U.S. Census Bureau. The report also found that 41 percent of those, ages 21 to 64, with any disability were employed, compared with 79 percent of those with no disability.

Furthermore, the United States Department of Labor’s Office of Disability Employment Policy reports that the unemployment rate for people with disabilities is 8.7 percent, nearly more than double that of people without disabilities (4.6 percent).

A service dog can lead to an overall healthier life, says Carol Borden, founder and CEO of Guardian Angels Medical Service Dogs, headquartered in Florida.

“We have seen people on mega-doses medication, 12 to 42 different medications a day. Once we pair them with a dog, under their doctor’s care many are able to dramatically cut down or get off medication altogether,” says Borden. “They go back to work, school, travel, start business things that they were only able to dream of before.”

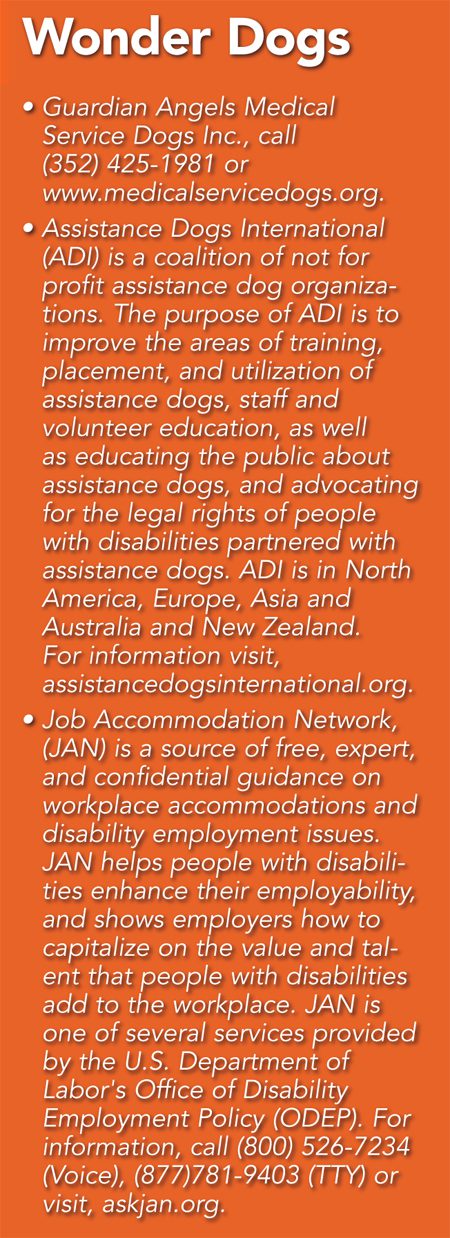

Founded in 2010, Guardian Angels trains medical service dogs, pairing them with people with disabilities. The nonprofit donates these valuable service dogs to those who apply and qualify.

Borden says service animals are similar to a piece of medical equipment. And like Dash, they can prevent their owner from not only going into blood sugar induced coma but can avert further injury.

A diabetic like Inglis sometimes can’t detect the change in their blood sugar and can start going into a coma, fall and hurt themselves.

“If a dog could have alerted a diabetic as soon as their points were too high or low, that person could have taken corrective medication.”

The National Education for Assistance Dog Services (NEADS) says the use of dogs to assist the blind is well documented all over the world and systematic training methods were established as early as the 1750s in France. In America, the first guide dog school for the blind was opened in 1929.

But while service animals have improved and saved lives, they can still be a cause for controversy.

Service dogs and discrimination

In 2012, Brent and Stacy Fry filed a lawsuit against the Napoleon School District and the Jackson County Intermediate School District by the American Civil Liberties Union of Michigan after district officials barred their daughter Ehlena, from bringing her doctor-prescribed service dog, Wonder, a Goldendoodle, to school.

Wonder helps 12-year-old Ehlena, who has cerebral palsy, balance, open and close doors, retrieve dropped items and perform many other tasks. He is also hypoallergenic and trained to stay out of the way when he is not working.

The ACLU contends that in 2010 the districts discriminated against Ehlena, then 5-years-old, in violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) by failing to make reasonable modifications to their policies and practices.

The ADA prohibits discrimination and ensures equal opportunity for persons with disabilities in employment, state and local government services, public accommodations, commercial facilities, and transportation, according to www.ada.gov. Entities that have a “no pets” policy generally must modify the policy to allow service animals into their facilities.

Under the ADA, a service animal is defined as a dog that has been individually trained to do work or perform tasks for an individual with a disability. The task(s) performed by the dog must be directly related to the person’s disability.

“They are allowed public-access everywhere,” says Borden of service dogs. “You couldn’t tell a person who is wheelchair-bound, ‘no you can’t come into my restaurant,’ or ‘no you can’t work for me, even though it is a desk job, you have to leave the wheelchair at home.’”

However, the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled 2-1 that claims brought under ADA should be thrown out because the Frys never asked for an administrative hearing under a separate federal law, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

However, the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled 2-1 that claims brought under ADA should be thrown out because the Frys never asked for an administrative hearing under a separate federal law, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

The IDEA ensures and governs how states and public agencies provide early intervention, special education and related services for children with disabilities.

The ACLU argues that IDEA administrative hearings are only required for violations of the ADA, if the student is seeking relief that is also available under IDEA and, in this case, the money damages sought by her parents are not available under IDEA.

The U.S. Supreme Court was slated to hear the oral argument Oct. 31, on whether the Frys could bring their lawsuit directly in federal court or instead were required to first present their case in state administrative proceedings, according to www.scotusblog.com.

“If Ehlena loses in the Supreme Court, students with disabilities who seek to vindicate their rights under the ADA in court will be forced to go through a lengthy, time consuming and emotionally draining administrative process under IDEA—even when the relief they seek in court is not available under IDEA,” says Michael J. Steinberg, Legal Director, ACLU of Michigan, which brought the suit with the Frys.

In addition to Steinberg, the Frys are represented by Samuel Bagenstos, a University of Michigan law professor who will argue the case. Also helping are Jill Wheaton and James Hermon of the Dykema law firm, National ACLU Disability Counsel Susan Mizner and Claudia Center, and National ACLU Legal Director Steven Shapiro.

Steinberg says the ACLU of Michigan has written letters on behalf of individuals with service dogs, and has filed other lawsuits on behalf people with disabilities, but Ehlena’s case is different.

“This is our first lawsuit addressing the right to a service animal,” says Steinberg. “The truth is that most institutions, including schools, honor the right of individuals with disabilities to be accompanied by a service animal. To the extent there’s a problem, it can usually be address through a letter or a phone call.”

In service to veterans

Patrick Tackett, an Army veteran who served tours of duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, employs Trooper, a 3-year-old German shepherd, as a service dog. Tackett, a Michigan resident who lives in Sanilac County, finds it unbelievable that service dogs are denied access such as in the case of Ehlena Fry.

“If Trooper can assist and aid me, then yes this dog should go everywhere I go,” says Tackett, a married father of one. “It is the same for this little girl. It is unfortunate, I know a couple of service members that had to deal with that.”

Guardian Angels Medical Service Dogs donates its trained service dogs to all who qualify but 90 percent of its dogs are paired with veterans like Tackett, says Borden.

Borden says veterans like Tackett are dealing with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), which may also be complicated with a combination of combat disabilities such as mobility, missing limbs, seizures, hearing impairment and traumatic head injury.

An airborne infantryman, Tackett served more than six years and was medically retired as a Sergeant E-5. During his service, he fractured vertebrae in his back when an improvised explosive device (IED) detonated.

Before Trooper, Tackett found it difficult to leave his home. And when he did, being in large crowds would trigger panic attacks.

After talking to a friend fellow veteran, also dealing with similar issues and in the process of trying to get a service dog, Tackett too considered the option.

Through research, a persistent, loving wife, and the help of caring friends, Tackett learned about Guardian Angels Medical Service Dogs, which eventually paired him with Trooper.

“I think from the time we applied to the time when I went to Florida to be paired, it was roughly six months,” says Tackett. “Trooper was trained and tailored to where he is not a full mobility assistance dog but if I drop things, he can pick them up for me. I still have pretty good mobility, but he keeps me from bending and squatting.”

Additionally Trooper is trained to recognize and wake Tackett when he has a night terror.

Tackett says he still faces daily challenges but Trooper makes them surmountable.

“Service dogs are not a cure-all,” he says. “I still deal with a lot of the same issues. When I go out in public, I still keep it limited just due to the fact that I don’t like putting myself in those positions. Trooper makes it easier for me to be in public. I am able to kind of relax and allow him to tell me what is going on around me.”

Services dogs are not only life-changers but can be life savers as well, says Borden.

Unfortunately many veterans suffering from PTSD are also at risk of suicide.

In July the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) released information from its most comprehensive analysis of Veteran suicide rates in the U.S., examining more than 55 million veteran records from 1979 to 2014 from every state in the nation.

The current analysis indicates that in 2014, an average of 20 veterans a day died from suicide. Since 2001, U.S. adult civilian suicides increased 23 percent, while veteran suicides increased 32 percent in the same time period. The risk of suicide is 21 percent greater for veterans.

Borden says Guardian Angels has not had a veteran commit suicide once paired with one of its service dog.

To date, Guardian Angels has successfully paired over 180 teams throughout the U.S. The organization spends $20,000 training each dog, which begins when they are three days old says Borden.

The third to the 16th day of life is the most rapid stage of the development of the neurological system of a canine, says Borden.

Dogs go through several levels of desensitization, socialization, confidence building, 50 hours of public access, fostering, house manners, advance skills tasks and the American Kennel Club’s Canine Good Citizen certification program that evaluates dogs in simulated everyday situations.

Borden says they have to be as invisible in public as possible and not be frightened by the common things that we normally take for granted that are not in a normal dog’s world.

“Not all people can be rocket scientists and not all dogs can be service dogs,” says Borden.

Then there is the cost of food, medical care, housing the dogs, utilities, rent and paying trainers.

Guardian Angels is one of the larger service dog organizations in the country with locations in California, Tennessee, Connecticut, Michigan, Pennsylvania and Illinois. It is pairing veterans and first responders nationally.

At its Florida headquarters, there are 85 dogs at various levels of training at all times.

But Guardian Angels involvement with the service dogs doesn’t stop when the training ends. There are multiple contingency plans for the working life of the handler and the service dog.

Service dogs are allowed at hospitals but someone must be there to care for the animals. Borden recalls late-night trips to the hospital emergency room, picking up a service dog for one of its single recipients admitted in ICU.

If the recipient should die, the service dog returns to Guardian Angels. If the dog gets sick or dies, the organization will replace it. Even if the team has training challenges, Guardian Angels will work with team and recertify them annually.

“We have seen people homebound for 25 years, people who haven’t been out of their bedroom in six months. In two or three days we have them in public, integrating back into families and society,” says Borden. “Not everybody does what we do. There is a lot that goes into that $20,000 that people never think about.”