The July jobs report capped a period of disappointing economic releases that collectively put the economy on recession watch.

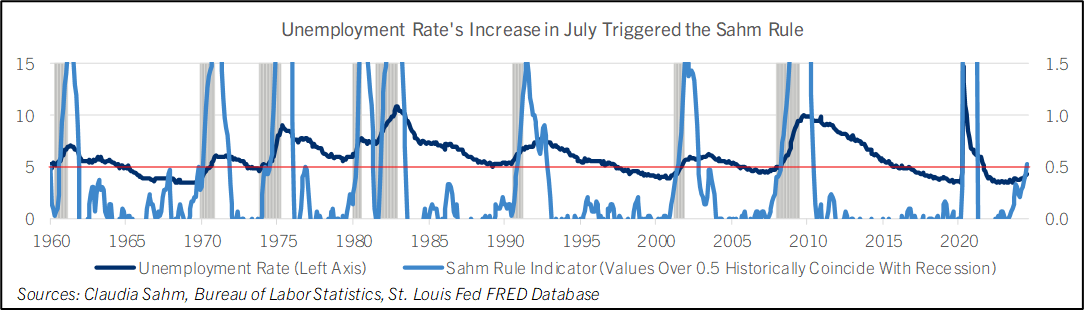

Jobless claims are rising, payrolls growth and wage growth are weakening, and the outlook for the highly cyclical manufacturing industry is deteriorating. Hurting market sentiment even more, the unemployment rate rose enough in July to trigger the Sahm Rule (See chart). This is former Fed economist Claudia Sahm’s observation that historically, when the unemployment rate’s three-month moving average rises above its low over the previous 12 months, the economy has already slipped into recession.

There are several reasons why the Sahm Rule recession indicator could be a false positive this time. Hurricane Beryl shut down large swathes of the Houston economy in July, affecting more than 2% of Americans—a headwind that is quickly fading. The auto industry retools in the summer months, which may be behind some of July’s weak manufacturing sentiment and hiring.

And many members of the recent wave of new immigrants arrived in the United States without jobs and looking for work, adding to unemployment. These collective factors could have raised the unemployment rate in July even as the economy continued to grow. In addition, the most widely followed survey of the service-sector showed it expanded moderately in July, and industries covered in that survey account for a large majority of U.S. GDP and employment.

Even so, this growth scare is a wake-up call to the Fed. Their dominant narrative in the last few years has been higher (inflation and interest rates) for longer: The post COVID-19 pandemic economic boom, flood of stimulus, and labor shortage shocked the economy into a regime of sticky high inflation, which only an extended bout of pain (or at least high interest rates) could return to normal. There is some evidence that sticky inflation has legs. The big pay increases negotiated by unions in the past year are still contributing to overall wage growth, as is the fast food wage hike in California. Service prices that reset infrequently, such as homeowners and auto insurance, are rising much faster than normal, and shelter inflation in both the CPI and PCE indexes is still too high.

But recent data suggest the inflation regime is shifting back to a cooler status quo. The union wage deals move the needle on wages in Michigan and other manufacturing powerhouse regions. But across the U.S., unions represent only about 6% of private-sector workers. Slowing hiring and quits in the rest of the private job market has more than offset the effect of union wage deals on earnings.

Regarding broader price trends, consumers got some price relief in the first half of the year from less expensive new- and used cars, household appliances, furniture, and electronics. The latest earnings call guidance from many consumer-facing businesses suggests discounting will broaden in the remainder of the year to touch more prices in grocery stores, on restaurant menus, and for services more generally. In addition, the labor market is clearly cooling even if the Sahm Rule likely exaggerates the extent.

The three-month moving average of payrolls growth slowed to 177,000 in the June jobs report, and July’s revisions lowered the April-to-June average to 168,000. That is too slow to keep up with the workers entering the labor market this year and fulfill the Fed’s mandate for maximum employment—and looks only at data collected before Beryl began clouding the measurement of the economy.

With the economy potentially at a pivot point, the Fed’s policymakers will want to make clear that they are ready to respond flexibly and nimbly if the economy weakens more than expected, as well as being prepared if inflation resurges. The Fed’s July monetary policy statement largely articulated this stance. But the Fed didn’t explain their plans to respond to a serious, self-reinforcing downturn—which absent some new inflationary shock could easily push inflation below their target—and markets are worried that the Fed could get blindsided.

Over the next few weeks, Fed policymakers will likely reassure markets that they are prepared for a broad range of outlooks, including downside risks. By emphasizing they are alert to the possibility of a regime change, the Fed can lower the risk of markets and the public overreacting and fueling a self-reinforcing loss of confidence. In addition, the Fed will likely see the August selloff as a sign that real (inflation-adjusted) interest rates are too high.

Even if the Fed still sees the risk of a serious economic downturn as limited, they will want to adjust interest rates to account for the considerable decline of realized inflation over the last two years. At the same time, the Fed doesn’t want to overreact to one weak jobs report, cut interest rates too far too fast, and reignite inflation. Nor do they want to overreact to financial market volatility, which has been aggravated by events in Japan that are unlikely to affect the U.S. economy, as well as by the seasonal weakness of financial markets in August.

Comerica’s latest forecast sees the Fed splitting the difference between overreacting and underreacting, and making quarter-percentage-point federal funds rate cuts at each of their next four meetings. A half-percentage-point cut is possible before year-end, but seems unlikely barring a large further deterioration of economic data. Instead, smaller cuts coupled with clearer forward guidance that describes the Fed’s willingness to cushion against a serious downturn would balance downside risks to growth against the risk that inflation revives, while also bolstering the public’s confidence in the economic outlook.

Bill Adams is a senior vice president and chief economist at Comerica. Waran Bhahirethan is a vice president and senior economist at Comerica.