• Both total and core CPI hit a new 40-year high in February as energy and food prices rose sharply.

• Inflation will accelerate near-term as the Russia-Ukraine crisis pushes food and energy prices even higher.

• Comerica’s March forecast downgrades the outlook for U.S. growth due to the drag from Russia-Ukraine, but does not foresee a recession in 2022 or 2023.

• Growth is slowing and inflation raging, but the outlook for business is better than in the 1970s’ stagflation.

• Risks to short-term interest rates are to the upside in 2022, but more double-sided in 2023.

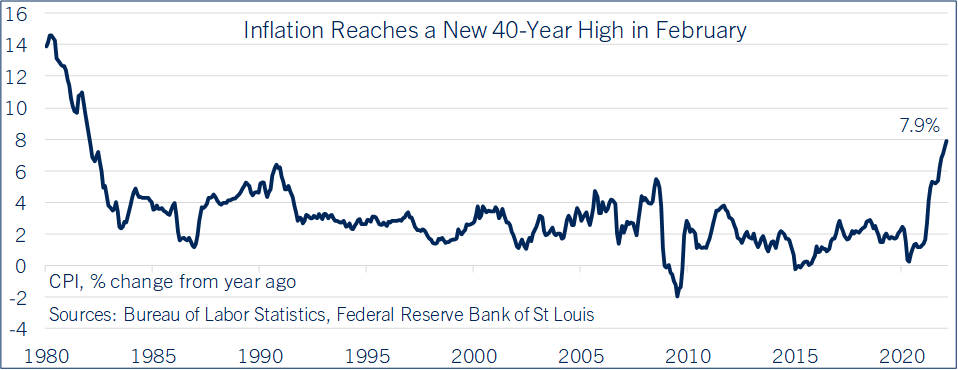

The consumer price index for urban households (CPI-U or just CPI) rose 0.8% in February after a 0.6% increase in January. From a year earlier, the CPI rose 7.9% after 7.5% in January. February marked a new 40-year high for CPI inflation in year-over-year terms. Inflation outpaced wage growth for a third consecutive month, with average hourly earnings up 5.1% on the year.

Energy prices jumped 3.5% in February after rising 0.9% in January and were up 25.6% from a year earlier. Energy markets anticipated Russia’s invasion of Ukraine even before Russian forces crossed the border February 24, pushing energy prices steadily higher over the course of the month. Energy accounts for 7% of the CPI basket.

The food index rose 1.0% in February after a 0.9% increase in January. From a year earlier, food prices rose 7.9% after a 7.0% year-over-year increase in January. Prices for food at home rose 1.4%, while prices of food away from home rose 0.4%. Food accounts for 13% of the CPI basket.

The CPI excluding energy and food a.k.a. core CPI rose 0.5% in February, down a hair from January’s 0.6% increase. Shelter costs rose 0.5% after a 0.3% increase in January, with rents up 0.6% after January’s 0.5% and owners’ equivalent rent of primary residence unchanged on the month at 0.4%. From a year earlier, core CPI accelerated to 6.4% from 6.0% in January and, like total CPI, was the highest in 40 years.

The auto supply chain snarl is gradually improving, leading to slower increases in vehicle prices. New vehicle prices rose 0.3% in February after no change in January, while used vehicle prices fell 0.2% after a 1.5% increase in January. New and used vehicle prices were up 12.4% and 41.2%, respectively, from a year earlier. New and used vehicles collectively account for 8.3% of the CPI basket.

Medical care services prices rose 0.1% after a 0.6% increase in January; they account for 7% of the CPI basket.

Inflation will accelerate in March and April as the knock-on effects of the Russia-Ukraine war push prices even higher at supermarkets, gas pumps, and on utility bills. Prior to the war, Russia was the world’s second largest producer of oil and natural gas, and Russia and Ukraine collectively exported over a quarter of the world’s internationally-traded wheat. Disruptions to supplies of those commodities will translate into another big hit to U.S. consumer spending power at a time when inflation was already historically high.

Comerica’s March U.S. Economic Outlook raises the forecast for inflation in anticipation of these knock-on effects from the Russia-Ukraine war. The forecast for CPI inflation is raised to 7.6% in 2022 and 4.0% in 2023, versus 5.0% and 2.4% respective forecasts in the February 2022 Economic Outlook. In year-over-year terms, inflation will likely hold in the high single digits through the summer months, even as monthly price increases increase. This is because prices rose very rapidly in month-over-month terms in the spring of 2021 as Americans were vaccinated and consumer spending surged much faster than the economy’s potential output.

Consumers will likely pull back on discretionary spending over the next few months, as inflation erodes purchasing power. Spending on goods that saw demand surge in 2020 and 2021, like electronics, recreation equipment, and other durable consumer goods, is likely to decline notably. Spending on services should be more resilient. Consumers who avoided restaurants and airports in 2020 and 2021 due to health concerns should trickle back in 2022, despite higher prices. Spending on cars and trucks should continue to recover, too, since that category has been constrained more by supply bottlenecks than demand, and bottlenecks are fading.

Despite slowing growth and raging inflation, the U.S. economy in 2022 does not really look “stagflationary” in the 1970s sense. Stagflation then was a combination of weak growth, high inflation, and chronic underperformance of corporate profits. The big difference today is that real incomes are falling—again, average hourly earnings are lagging inflation—a contrast to the 1970s, when unions routinely secured inflation-indexed real wage increases that outpaced growth of real hourly output, and kept the wage-price spiral twisting higher. Only 7% of workers in the U.S. private sector are represented by unions today. It is hard to see wage-price spiral effects taking root given the big structural changes in the labor market over the last half century.

The Federal Reserve is anxious to normalize U.S. monetary policy, with inflation far above their target of 2% (measured by the PCE price index, which differs slightly from the CPI), and the labor market close to meeting their definition of maximum employment. Comerica forecasts for the Fed to raise the federal funds target rate by 0.25% at their March 16 decision, then raise it another full percentage point by the end of 2022 to a range of 1.25%-to-1.50%. The Fed is likely to begin shrinking its balance sheet, a.k.a. quantitative tightening, this fall. Interest rates are more likely to rise faster than Comerica forecasts in 2022 than slower, given how bad inflation is, but risks to the interest rate outlook will be more double-sided in 2023. The Fed is likely to grow concerned about recession risks by then as U.S. growth slows, and oil prices could recede if the situation in Ukraine calms down.

Bill Adams is senior vice president and chief economist at Comerica.