To understand blockchain is to first grasp what it is not, and that’s Bitcoin.

The application is often conflated with the cryptocurrency, which runs on it, and that’s like putting Facebook on par with the internet.

Like the internet, though, blockchain, the underpinning of cryptocurrency, is seen as a revolutionary force in technology and business, potentially reshaping how transactions in banking, real estate and entertainment are completed due to the decentralized digital ledgers that are its foundation.

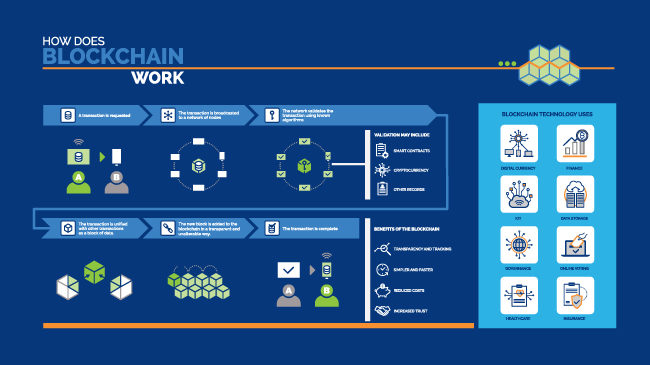

Through linked blocks, which are cryptographically verified through hashing and timestamps, blockchains provide secure documentation of every transaction.

Blockchain’s built-in security is key: its decentralized security features kicks in if any attempt is made to alter one of the blocks that was established as part of a transaction. That change would need to be made on all the blocks on the peer-to-peer network to take effect, thus modifying its DNA. Some experts say even a single modification would be impossible, given the number of nodes in the chain.

To underscore that assertion, IBM has fully embraced the technology through its “Blockchain-as-a-Service” platform, particularly in the area of supply chain management.

Through use of the open software platform Ethereum, “smart contracts” are being developed to negotiate services and other tangible assets, which could radically change how consumers buy goods on auction sites like eBay or download copyrighted material from providers like Netflix.

Eliminating the middleman

An undercurrent of a blockchain peer-to-peer framework is eliminating the middleman.

“I think (blockchain) has the potential to be a real disruptive force business-wise, in a positive way,” said Keith Harder, Rehmann Financial principal and financial advisor in Troy. “I think it’s one of these technologies that has the potential to really change and redevelop a number of industries.

“And I know that this is a bold statement. I think that there is a lot of hype out there and I’m not sitting here today trying to overhype the prospects of it, but I think it really does have some tremendous potential and a few concerns out there as well.”

Detroit Blockchainers, a group of developers, techies and cryptocurrency enthusiasts, only see the technology’s upside. The group meets on Tuesdays during cold weather months in the Fisher Building. On summer nights, the group gathers informally at Capitol Park in Detroit.

The group also partners with North End Tech Team for a weekly hack night on Wednesdays at Red Door Digital at 7500 Oakland Avenue in Detroit.

Some members also belong to EOS Detroit, a developer group, and Detroit Blockchain Center, a nonprofit advocacy outfit.

Detroit Blockchainer Andrew O’Brien, a software developer for Nexsys Technologies, part of the Quicken Loans family of companies that includes title arm Amrock, is understandably fascinated with blockchain’s capabilities in terms of real estate transactions, which are typically bogged down in bureaucratic paperwork.

“My problem right now is there is a lack of alignment of incentives because the county recording office is being paid every time they pull a record for someone,” said O’Brien, 22, who grew up in North Andover, Mass., but moved to Detroit after graduating from Georgetown University.

“So if you were to go to someone who’s getting money off of this archaic system and tell them there’s a better way to do business such that you can digitize those records and have them immutably available on some kind of system that is validated peer-to-peer, I think that’s probably going to be one of the greatest barriers to transferring of a national title system (based on) blockchain,” he said.

Disrupting the real estate industry

Last year, velox.RE conducted the first real estate transaction using blockchain in Cook County, Ill., so the technology is there, O’Brien said. The drawback for blockchain is when a transaction actually becomes legally binding.

“One of the big things is that until your title is recorded in a recording office, it’s not technically yours yet,” O’Brien said. “There are a few different things that happen when you’re transacting a property. One is obviously when you are at a closing you’re doing payment and conveyance, so payment as in, ‘I’m writing a check for the house,’ conveyance as in you’re doing a quit-claim deed perhaps, which means you give away your interest in the property and then I sign a deed, which allows me to own the property. But that’s not actually fully confirmed until it’s a recorded account in a recording office.”

He continues: “So, we’re in the closing room. I may pay you and all the papers are there, and next day our title agent will hopefully go out, if they’re good, to their county recording office and actually file it with them. It’s called recording. That’s what actually gives it that kind of legal standing. Until then, it’s hard to really tell who owns what in a certain legal sense, where in a blockchain everything would happen immediately, the payment, the conveyance and the recording would happen in a single layer.”

Thom Ivy, another Detroit Blockchainer, is using the technology for a humanitarian purpose. He’s developing a reporting process through blockchain where survivors of sexual assault can share information anonymously without fear of retribution.

Ivy has been involved in blockchain and cryptocurrency since 2010, first using Bitcoin to play blackjack.

His pursuits in all things blockchain have taken a more serious tone in recent years.

“So in the day and age of (Brett) Kavanaugh’s trials, Nasser, Cosby, I’m particularly interested in taking all these people who know something to be true, which is that someone victimized them and coordinating their knowledge in a way that is reliable while also protecting them from retribution on the part of their victimizer,” said Ivy, a Detroit resident who is a marketing consultant and philosopher. “So, essentially, we use a bit of encryption of blockchain technology to prevent censorship or interference by particularly powerful actors, like politicians or billionaires, which we see play out all the time in the U.S.”

He adds: “It’s pretty technical, but basically we’re just using a decentralized way to allow people to anonymously report social predators in a way that is mathematically reliable, meaning that it prevents against false accusations as much as it prevents actual future action.”

Better than ‘best before’

In another scenario, blockchain technology is being employed in an effort to respond quicker in cases of food contamination.

Walmart has teamed with IBM through a pilot program, Food Trust, to create a digital ledger to track fresh produce from the farm to grocery store shelves, Forbes reported.

“If you think about it, Walmart is buying green leafy vegetables from hundreds, if not thousands of suppliers and producers,” Rehmann’s Harder said. “So if they’ve got an outbreak in southern California, it’s like goodness sakes, how do they track where it came from?

“Well, I think blockchain technology is going to really help them drastically improve that and be able to identify, ‘OK, who bought it? Where did they buy it and when did they buy it?’ and be able to track that all the way through.”

Harder also sees those blockchain technologies potentially extending to nonprofit giving.

Instead of using third-party solicitors or even Go-Fund Me pages, 501(c)3 groups could raise money directly through distributed ledgers.

Through blockchain transparency, donors would see better accountability of their money, Harder said.

“I might be able to get some information by logging onto their website, but ultimately if I’m going to write them a check for a thousand dollars and put that in the mail and give that to them, I am kind of trusting that they are going to do good with that $1,000 donation,” Harder said. “But I am not really sure what happens to that $1,000.”

He continues: “Using blockchain technology, I can gift a charitable organization and really track that from the moment that $1,000 is in my hands to it going to the charity, to the charity then allocating it to administrative costs, marketing costs and then, ultimately, whatever causes and details of that to which it is going. I can monitor that and actually holds the charitable organization more accountable because the transparency is right there.”

For the time being, though, the forces behind blockchain are for-profit endeavors.

Shifting the financial model

In cryptocurrency, authenticators — or miners — are offered financial incentives. Miners earn 12.5 Bitcoins for every block created. That amount will be reduced to 6 BTCs in 2021.

A new block is created every 10 minutes, which fuels a market where there are more than 1,000 cryptocurrencies available.

Ethereum is proposing a switch to a proof of stake model, which is less energy intensive and relies on validators — or forgers — who would receive 2 to 15 percent of transaction fees rather than a set amount. The percentage would vary, depending if there are too many or too few authenticators in the predetermined pool.

“What they have said is this proof of work has become way too inefficient, too many people are participating,” said Naveen Khanna, the A.J. Pasant Endowed Chair in finance at Michigan State University. “There is over participation and, consequently, a lot of resources are being wasted. A lot of resources are being consumed just to mine and if you have over mining and then it is inefficient.”

He explains further. “Let us now go to a new concept called a proof of stake, which means if you own a lot of Bitcoins, you have more of a say with respect to certifying every deal or every new blockchain which is going to be created. So that is again not going to be very different from large stockholders, or large blockholders, controlling a major part of the decision making in any firm.

“So we are trying to decentralize. If we move to proof of stake, I think we are moving away from decentralization.”

Detroit Blockchainers’ Ivy concedes the proof of stake model has elements of centralization, which may seem like an anathema to blockchain’s purpose.

“To clarify the reasoning there, is that you’re not going to take any actions which decrease the worth of your money,” he said. “And you if you have a lot of Ethereum, you’re not going to mess with the system because that’s your money going down the drain.

“You’re going to reduce the system’s trustworthiness or effectiveness. And, therefore, your money will be worthless.”