It has to be a frustrating situation.

In a world where the basic laws of supply and demand would suggest that a healthy economy and low unemployment are near ideal, industry and educators alike face an imbalance that may be years away from being fully corrected.

Before diving in too deep, it’s important to clarify what the terms “talent gap” and “skills gap” really mean, one obvious reason being that some would say it’s really the type of talent that’s at issue.

There are lots of talented people in the marketplace. Always have been.

But when it comes to some of the most sought-after people for open jobs in occupations such as carpentry, electrical, plumbing and other trades that have historically involved an education track set apart from college or university, industry observers say there’s a problem.

And it’s getting bigger.

Let’s also stress a key point: while there are, indeed, challenges, there is also hope. Companies, educators and government entities are recognizing the gap (whichever term is preferred) and moving toward solutions.

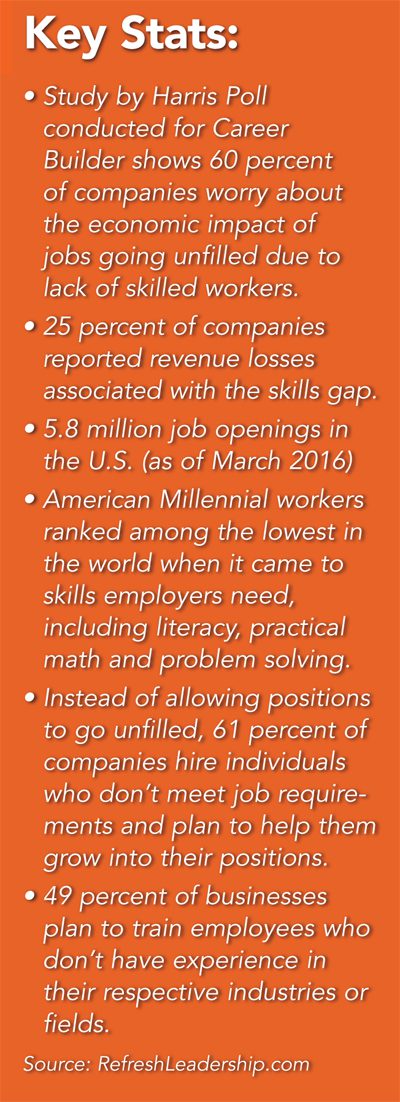

There is also a certain sense of urgency, underscored by both data and anecdotal evidence that suggests the imbalance faced in a market for people with the qualifications needed for jobs is likely to widen before it narrows.

What many agree on is that the combined energy of many is needed to help drive fundamental change.

One of those is Gregory E. Pitoniak, who serves as CEO of the Southeast Michigan Community Alliance, the Michigan Works! affiliate that serves Monroe County and Wayne County, excluding the City of Detroit.

“The reality that we’re dealing with is that the employers we serve have positions open and we have difficulty finding candidates with the qualifications to fill those positions,” says Pitoniak, a former politician who served as the full-time Mayor of Taylor and later as a State Representative. He’s also headed the Economic Development Corporation of Wayne County.

Pitoniak says that gap has been created and sustained, at least in part, by a generation of adults who have influenced the choice of their children as to what to pursue from a career standpoint.

“One of those is that there is a perception of manufacturing that comes from thinking about the past,” says Pitoniak. “People remember a time when those kind of jobs were very cyclical in nature and the work was dirty and hard. Now the jobs that are available are in settings that are typically very high tech and clean.”

The problem is exacerbated in that employers are not only looking to add employees as their business grows, but they’re eyeing a significant percentage of their current workforce.

The problem is exacerbated in that employers are not only looking to add employees as their business grows, but they’re eyeing a significant percentage of their current workforce.

As recently as last December, Kevin Koehler, president of the Construction Association of Michigan, said three out of four skilled workers in the industry he represents will be retiring or at the age of retirement in the next 20 years.

Another major reason for the decline happened a few years ago, when the recession affected many manufacturing jobs. Many skilled workers left due to either job cuts or finding work in another field, but now that the recession is over, filling these jobs has become a difficult task.

It’s a problem that business leaders across the state are facing.

EDSI is a Dearborn, Mich.-based workforce development, customized training and consulting company, where Jim Bitterle is managing partner.

Bitterle agrees with the point made by Pitoniak (who is a client) that parents may be laying their experience of a very different workforce dynamic on the shoulders of their children.

“They’re pushing their kids to go get a college degree, but sadly, more than 50 percent of those never get a degree and nobody is really pushing training for careers in manufacturing,” says Bitterle.

Still, EDSI is taking steps to at least make a dent in the problem, including so-called boot camps for high school students or recent graduates, as well as opportunities for specific skills training.

There’s also a pre-college internship program that is designed to be more appealing to parents who otherwise become a major obstacle on the path to training for jobs in the skilled trades, even though these occupations are high paying and numerous.

One that will agree with those sentiments is David Barrett, who serves as director of Talent Management at Cascade Engineering, based in Grand Rapids.

The engineering firm works actively with Davenport University on what is essentially a “grow your own” approach to the skills gap problem, offering internships to someone who may be already working at the company in a classic “on the job” opportunity.

It’s a response to the skills gap issue, says Barrett, which isn’t getting better, at least for the foreseeable future.

“If anything it’s getting worse,” he says. “It’s starting to become a war for talent, a bidding war.”

What Cascade Engineering is doing is working with professionals who understand that problem and have the resources to tackle it.

It’s also embracing a mindset like that common in Germany, where skilled trades are actively promoted.

The pinch points, says Barrett, aren’t necessarily on the engineering front line, but on the technical side.

“It’s in the maintenance department where our war for talent is being waged,” adds Barrett, who stresses that the jobs that are available today are much different than people of another generation might be thinking.

“These are not the low-end, dirty manual jobs that some people think they are. We’ve got people programming maintenance robots. But schools don’t seem to be promoting these as occupations worth pursuing as a lifetime career.”

Barrett says the Davenport connection, which has been in place since 1990, has been “very effective” for Cascade Engineering.

Another participant in the quest for more skilled trades candidates in West Michigan is Jacob Maas, CEO of West Michigan Works!, which covers some 11 counties surrounding and including Grand Rapids.

Maas says the organization he has been with for some 13 years, the last three as CEO, has seen its own form of transition, from a day when training was more generalized—a “buckshot” approach—to one where focus is now the strategy of choice.

“It’s a very employer-led strategy, very private sector focused,” says Maas, whose group helped organize a job fair geared to high school students who have yet to decide what career path they will take.

Launched in 2015, the annual MiCareerQuest involves more than 70 school districts and this year attracted at least 9,000 students and 1,000 volunteers. Students at the one-day, six-hour event (held at DeVos Place in Grand Rapids) rotated through sections representing four industries—construction, healthcare, information technology, and manufacturing.

More than 90 employers were on hand to engage on a one-on-one basis with what they hope are at least a few of their future staff.

The chances of that taking place are strong, given the fact that in West Michigan, some 37.5 million boomers are expected to retire in the area within the next decade, with only about 21 million entering the workforce in that same time period.

To be sure, the gap issue facing companies in Michigan, whether in the Greater Detroit or the Western part of the state, is not unique.

Mary B. Young, principal researcher in the Human Capital group of The Conference Board, a New York-based nonprofit that is funded by some 1,200 public and private corporations, says companies in the past tended to focus on a “buy, build, or borrow” strategy for their talent acquisition, a reference to hiring, training or the use of temporary workers or consultants.

Young says one of the challenges in closing the gap is that companies typically don’t look far enough ahead to make much of a difference in their strategy.

“When they’re doing strategic workforce planning, the business strategy could be three to five years, but not much further than that,” she says. “With that in mind, the company is focused on what capabilities it needs to fill within that time period.”

And that is, in itself, a challenge.

“It’s very hard to see very far in advance,” says Young. “You want to think about how the organization is going to have to change and that isn’t always easy to do.”

Young’s report on the subject—”Buy, Build, Borrow, or None of the Above?”—describes how three companies, General Electric, Lockheed Martin, and Southern California Edison, are essentially rethinking the dynamics of their workforce challenge.

Their approach, as Young describes it, includes engaging a broad group of stakeholders to ensure that the strategy they use is aligned with changes in the operating environment and business priorities.

They also take an approach that continuously evaluates capabilities and skills—in that order.

“More and more companies are using alternatives to ‘owning’ the talent themselves,” says Young. “There’s now more use of platforms that connect with talent from outside the organization and companies that are making progress in this area are challenging the assumption that their solution is going to be employees.”

Back in Michigan, taking the long-term approach is an organization that is committed to making the kind of change necessary to help close the gap.

Talent 2025 (www.talent2025.org) was formed in 2009 after business leaders in the area, including Cascade Engineering CEO Fred Keller, began talking about the steps that would be needed to “catalyze an integrated talent system that meets the needs of employers now and in the future.”

Kevin Stotts, who serves as president of the organization, says Talent 2025 takes a three-step approach to solving the issue, the first of which is to eliminate the gaps in information about the nature of the problem itself.

says companies, faced with the challenge

of finding the right person for a job, are

innovating in new ways.

“We’re doing a lot of original research, data collection and analysis,” he says. “What we’re trying to do is understand the problems, what is working locally, across the country, and then advocating for policies that will help solve those problems.”

The second part of the overall strategy is to fund the priorities that flow from that gap analysis, the ones that will have the biggest impact on the organization’s goals.

The third step is to continue the advocacy role, Stotts says.

It’s the approach of the dozen working groups at Talent 2025, each headed by a member of the CEO Council, that has served to actually get things done, he adds.

“It’s leader to leader,” says Stotts. “That’s where the work gets done. They agree on the problems, agree on solutions and collectively execute.”

One of Talent 2025’s participants is Davenport University, where David Veneklase is executive vice president for Organizational Development.

Veneklase says many of the school’s more successful client companies have come to trust Davenport’s focus on a long-term approach to talent acquisition and development.

“Because I have long led HR-related functions, I understand those issues and can relate very well to HR executives,” says Veneklase.

Another Davenport client is Galaxe.Solutions, an IT services company where Ryan Hoyle is vice president of Business Development and Talent Acquisition.

In 2010 Galaxe, which has offices in North America, Europe and Asia, launched its “Outsource to Detroit” initiative as a way to promote the area as an international IT hub and onshore alternative, essentially repatriating information technology jobs to the United States.

Hoyle is clear, however, that the firm’s success in recruiting talent won’t come from merely convincing someone to leave one company and join another.

The connection with Davenport, which is in its early stages of development, includes steps like creating internships and other traditional means of getting graduates into companies represented by Galaxe.

“We’re extremely optimistic at this point,” says Hoyle of the effort that includes clients such as Quicken Loans and Guardian Alarms, where there is a compelling need for people able to work, or willing to be trained, in technical roles with these companies.

Hoyle says he’s enthusiastic about the potential for not only closing the gap, but improving the quality of new hires by identifying and designing educational programs with schools like Davenport.

David Lawrence, who heads Davenport’s Institute for Professional Excellence—the division that creates and runs corporate business partnerships like the one Galaxe is exploring—is very familiar with the story about companies not being able to hire as many people as they need.

One advantage that IPEX has in the marketplace is price, that being a factor that has Lawrence taking advantage of the resources of Davenport that are already in place to serve the degree side of the organization.

“It’s a different price point,” he says.

Also on the “solutions” side of the talent gap problem, SEMCA’s Greg Pitoniak, even while acknowledging that a pipeline of talent for specialized positions needs to be filled, cautions companies not to be unrealistic when they specify the skills that are needed for a job.

“The reality is that there are people who are available who could do a particular job in a relatively short period of time if they were trained on the job,” he says.

Hope seems to be a vital part of the ultimate solution to closing the talent gap, at least hinted at by Amy Lui Abel, another researcher at The Conference Board, who heads the organization’s Human Capital practice.

Some companies, she says, faced with a disconnect between demand and supply, are investing in simple training programs to stave off the problem.

“People are trying all sorts of things, including paying for someone to earn a degree, sometimes in fairly narrow areas.”

At least one company, faced with a shortage of data scientists, was able to break down what was a complex set of requirements into three distinct roles.

“The result was a new role that had three legs, each working together as one.”

EDSI’s Bitterle, whose company consults nationally in workforce development, makes a final pitch to parents (he’s also the father of three boys under 20) who might otherwise steer their kids into a college program that isn’t necessarily going to help them get a job once they graduate.

“The real message is for them to get educated in something that they love, that they can get a job and get money,” says Bitterle.

He also has a word for companies that should be elevating the role of human resources from a functional role to one that is more strategic in its approach.

“Everyone is out there trying to find people who already have the skills they need. But what’s really needed is some strategic thinking. We’re not just going to find those people. We need to develop them.”

Bitterle also says the educational system must bear some of the responsibility for changes that are needed.

“Schools need to be open to getting students into skilled trades and the construction and manufacturing opportunities that exist today. There’s nothing that says just because they do that they can’t go back and go to college at some point. But we need to make sure students are exposed to the trades. There are people who will benefit from being able to do things with their hands.”