There was never a time when the modern city of Grand Rapids saw actual rapids chopping up the waters of the Grand River as it snaked through the city.

The rocks that created the original rapids for which the city was named were quarried to build the foundations of Michigan’s second-largest metropolis. And dams were built for flood protection more than a century ago, diverting water into a canal that was then used to turn mill wheels to grind grain and cut lumber.

But we are beginning to live in a new era of urban planning, when it’s no longer an either/or proposition to enjoy nature and outdoor recreation while living in a large city.

That’s why an idea that seemed like a fantasy when it was first proposed about seven years ago at a Master Plan meeting has gained hold and has taken the form of a $30-million project to bring some really “grand rapids” back to its namesake city.

It’s a project that is expected to quickly pay for itself, and then some, with an estimated $15.9 million to $19.1 million flowing in the form of expanded recreational use of the river and riverfront, according to Grand Rapids Whitewater, a nonprofit group.

“When the philanthropists starting writing checks, it kind of caught the attention of the city,” said Grand Rapids Mayor George Heartwell. The project got a shot in the arm in 2013, when it was named one of 11 Urban Waters Federal Partnerships.

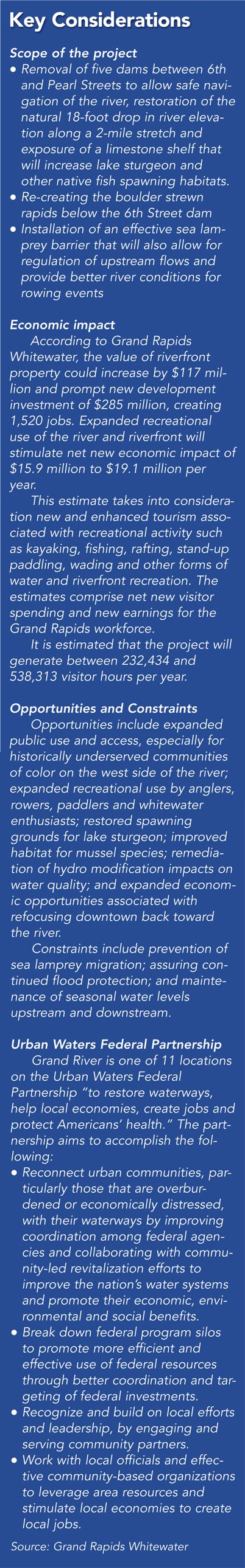

Construction should begin in 2016, assuming all the money is raised and the various agencies cooperate. The plan also includes removing five dams, which will open up an area downtown for whitewater kayaking or canoeing.

There will also be about 80 acres of water shallow enough to allow wading by anglers intent on bringing home trout and salmon.

“Right now, people wade the river, but at their own peril,” Heartwell said.

As for the rapids, that will come with introduction of new boulders below the 6th Street dam.

It’s all part of a larger vision for downtown Grand Rapids called GR Forward, where economic and environmental concerns are not mutually exclusive.

According to Grand Rapids Whitewater, the value of riverfront property could increase by $117 million and prompt new development investment of $285 million, creating 1,520 jobs. And literally, the “face” of downtown buildings will be turned toward the river.

That’s the economic part, and it’s all very exciting.

As for the environmental piece, a consequence of getting rid of the dams is invasive aquatic species, especially the sea lamprey. So, another barrier will be built farther upstream. Then there are concerns about flooding. The city is working with FEMA and the Army Corps of Engineers on flood management.

Another hurdle relates to managing stormwater.

Heartwell calls the issue peripheral, but it also gets at the heart of current perceptions regarding the Grand River’s muddy appearance.

“We’ve not made the kinds of investments in stormwater management that we should,” Heartwell said. But, after the end of the 2015 construction season, the city will have completely separated its sanitary and storm sewers, with sewer overflows no longer going into the river. For the most part, however, stormwater rushing into the city’s storm drains still goes directly into the Grand River.

Environmental education

Taking a lead role in environmental planning is the West Michigan Environmental Action Council. Executive Director Rachel Hood says it’s a great time to make the river serve as a focal point for the city, to replace concrete walls with “inclusive design schemes that help us achieve both goals of managing flood waters and put people in the water, or at least closer to it.”

Hood doesn’t think the environmental and business concerns differ, nor are they in conflict. Rather, it may be a matter of timing and priorities. “It’s a prime opportunity, from an environmental standpoint, to place some focus on water quality opportunities that the state of Michigan and our region has yet to achieve,” she said.

“Everybody is really captivated by this vision, and this idea, which is wonderful, but how do we leverage that attention to help move some of the state’s water quality goals forward and the region’s as well. That’s the big question.”

The major pieces to the big question involve several sources of pollution: primarily stormwater runoff and pathogens from agricultural communities. Hood says adoption of best management practices by the agricultural community and city engineers should take care of issues such as animal feeding and other small animal operations that may or may not have appropriate buffers.

There is also a need to educate civil engineers, landscape engineers and developers in designing communities that capture stormwater on site rather than let it travel into creeks, streams, rivers and ultimately the Great Lakes.

There is also a need to educate civil engineers, landscape engineers and developers in designing communities that capture stormwater on site rather than let it travel into creeks, streams, rivers and ultimately the Great Lakes.

“This is an interesting point because I think there’s a misconception among some of the communities that low-impact development is more costly. In fact, it is a way to create a lot of savings,” Hood said.

These are important things to consider if we’re truly talking about a change in the way cities are being built – one that changes this false choice between development and environment.

“The professions are slowly coming around on this. Frankly, it’s largely a generational issue. Especially in Michigan, I think you’ve still got a lot of folks who are nearing the ends of their careers and it’s as simple as people not wanting to learn new tricks five years before they retire.”

Through the end of June, public input will be sought on the river plans – what they’re calling the “wet” (the river, itself,) and the “dry” (river corridor) portions.

Hood said the public needs to understand enough of the science involved, and how a combination of best practices and sound science can “create the changes we want to see in the river, both ecologically and in recreational opportunities.”

Get out on the water

When it comes to recreational opportunities, that’s Jeff Neumann’s department. He runs GR Paddling – whose motto is “Carpé Aqua” – which ramps up every summer by taking tourists kayaking and canoeing on the Grand River. And while his customers don’t go paddling downtown (well, currently nobody really can), the effect of a river free from pollution and filled with white rapids, and people enjoying it, will have a great psychological benefit.

“I think it will bring a whole new respect for the Grand River for the folks who are down here,” Neumann said. “Right now, they have this opinion of the river. They think it’s polluted, nobody can paddle on it, you certainly can’t swim in it. And that’s definitely not true.”

Jon Holmes is store manager for Bill & Paul’s Sporthaus in Grand Rapids, which rents and sells kayaks, among other things. “The dams are the big danger, so if they can just get those out, downtown would be completely navigable and probably would be a great place to paddle,” Holmes said.

While rentals are but a small part of the business, just having the option of paddling in downtown Grand Rapids could help sales considerably.

“Now, if you want to even think about being a whitewater paddler, you pretty much have to either go up to Petoskey or down to South Bend to even get a taste of that,” said Holmes.

For Neumann at GR Paddling, the change will bring something hard to define back to river. “When they first started talking about this years ago, I thought it was pretty silly,” Neumann said. “But the more I looked into it, I’d walk over to the river all the time and I’d just think, ‘man, we’re missing something here.’”

In a few years, that “something” could be businesses facing the river, anglers wading in and fishing, bike paths and parks along the banks, and white water once again grandly splashing against boulders along the great river in Grand Rapids.

A look at Ann Arbor’s Argo Cascades

If Grand Rapids wants to peer into one of its possible futures, it just has to look about 130 miles to the east to Ann Arbor and that city’s highly successful Argo Cascades project. Before 2012, a 3.7-mile course on the Huron River, through the city, was popular with boaters, but they had to endure a stagnant millrace and concrete barrier with a very difficult portage. About $300,000 later, kayakers and canoeists were treated to a series of drop pools and a boat bypass that eliminated the portage.

It didn’t take long at all before the economic benefits almost literally came pouring in. According to the City Parks Alliance, in 2011, there were 38,000 visitors to the Argo Cascades. That rose to 50,000 in 2012, with an accompanying 58 percent increase in revenue. The first season, tubing rentals alone accounted for $20,000 in new revenue.

“The Argo Cascades have proven to be very popular and as a result the city of Ann Arbor’s canoe liveries have grown—a 91 percent increase in people renting boats since 2011 and a 95 percent increase in revenue predicted for fiscal year 2015 compared to 2011,” said Cheryl Saam, Ann Arbor recreation supervisor.

Saam said they are now the largest livery in the state, with 588 boats and 70,000 people paddling it each year. Seventy employees work at the Ann Arbor liveries. “And for beginners to paddle down the cascades, we’ve added inflatable kayaks and six-person rafts,” she said. “We now also offer tube rentals to tube the cascades and hike back and tube down again.”

Business is so good, the Ann Arbor City Council recently had to approve a new lease arrangement on some nearby property to handle the overflow parking.

The Argo Cascades connects with the 104-mile Huron River Water Trail, which was recently designated the 18th trail of the National Water Trails System. The Huron trail touches Milford, Dexter, Ann Arbor, Ypsilanti, and Flat Rock.

While the economic and recreational benefits are many, Argo Cascades faces a few challenges. First, the cascades aren’t for beginners in canoes. They can face difficulty steering, Saam said. “Therefore our canoe stack is located at the base of the 1,500-foot cascades and canoe renters walk to this canoe launch location. Also, we now have to screen everyone on their boating skills in order for them to paddle kayaks down the cascades.”

And if you want to kayak, you need to be screened for skills in paddling and, of course, swimming and righting a capsized boat.

Elizabeth Riggs, deputy director of the Huron River Watershed Council, said some serious challenges remain. “Low water levels trigger closure of the Cascades, since users would scrape their boats on the bottom, and the water needs to flow over the dam in the main river to prevent areas of no flow. Also, she said, although the city promoted the Cascades as a place where fish could pass, the waters move too fast for them.

Still, despite a few things not going quite as planned, the Argo Cascades at least keeps Saam and other livery workers, not to mention surrounding businesses, gainfully employed and busy. “The Cascades are crowded with boats, rented and personal tubes, and people hanging out,” she said.