Representatives of the National Wildlife Federation, the Great Lakes Compact and the brewing community sat down in Grand Rapids in October and looked into the future to get a clearer vision of how to protect the fragile water supply.

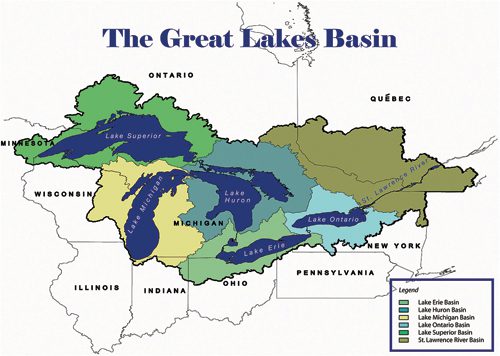

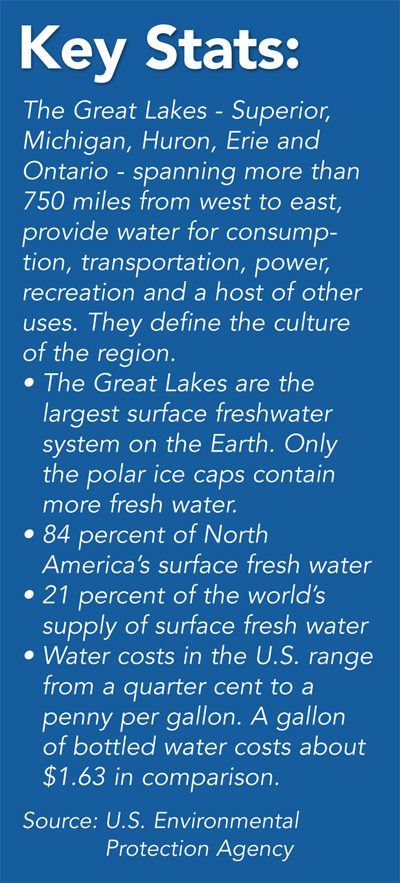

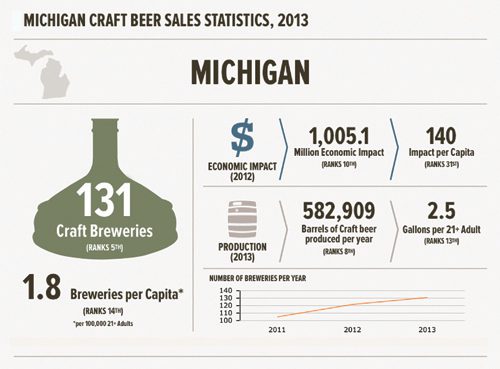

The Great Lakes have 21 percent of the world’s surface fresh water and 84 percent of fresh water in North America. Businesses, states, nations increasingly want a share of this vast resource that is so often taken for granted by those in the basin. One more statistic: Beer is 90 percent water, making its quality and preservation a key issue for Michigan’s nationally known brewing businesses. In 2013, the state had more than 130 breweries.

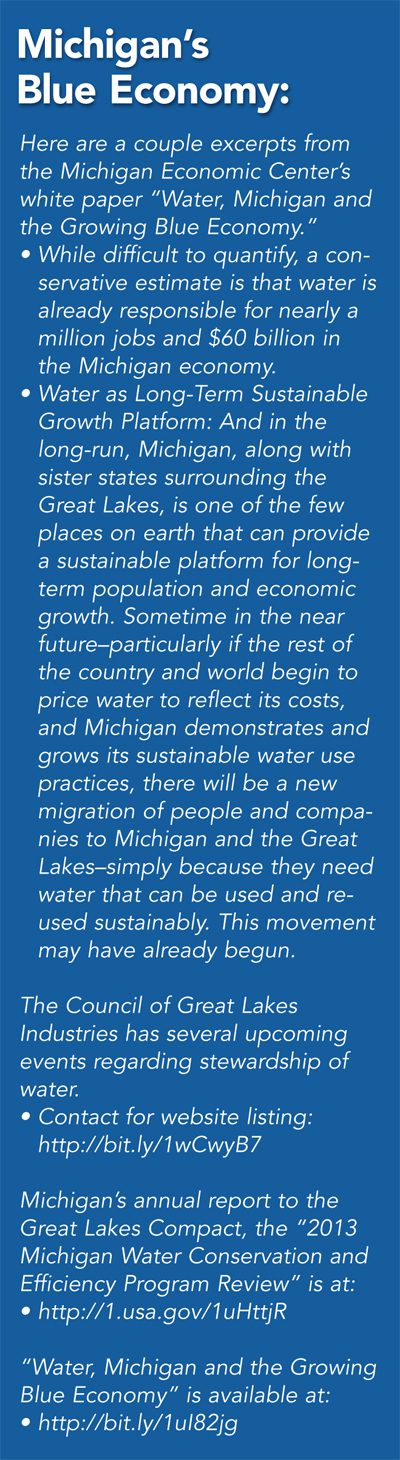

Michigan’s “Blue Economy” is estimated, conservatively, to supply a million jobs and $60 billion to the state economy.

“While the Great Lakes may be huge, they are so fragile,” said Marc Smith, policy director for the federation. “Don’t let the size fool you. Only 1 to 2 percent annually is recharged to the Great Lakes. Snow, rain … if you follow the trends we are not recharging enough. Everything in the Great Lakes basin flows through one of the five lakes.”

The water shortage of the 1930s Dustbowl spawned The National Wildlife Federation with a mission to create affiliates to protect and restore water resources.

“We are here to protect Great Lakes against diversions,” said Smith. “There are tons still happening throughout the Great Lakes. We can’t have a death by 10,000 straws. First we must prohibit diversions of water out of the basin. Second, we have to clean up our act on how we are managing the resource in the basin.”

The all-volunteer Great Lakes Water Conservation Conference, now in its sixth year, was organized by Lucy Saunders and more than 100 brewers and guest speakers. Past presentations are online at www.conserve-greatlakes.com.

The Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin Water Resources Compact, which came into force in 2008, treats the groundwater, surface water and Great Lakes tributaries as a single ecosystem. Predicted lower water levels in the Great Lakes, climate change and increased water use are cited as threats to the resource. The Compact seeks to protect against diversion from outside the basin and promotes proper stewardship within the basin.

Diversion history

The biggest water diversion to date has been the reversal of the flow of the Chicago River, which formerly flowed into Lake Michigan but now drains to the Mississippi watershed. That move, which took place in the 1880s, was prompted by concerns over the Windy City’s drinking water.

More than 130 years later, the diversion, which now accounts for an average of more than two billion gallons a day, remains controversial. According to waterwars.wordpress.com “A Brief History of the Chicago Diversion” posted in 2006, about 7 million people – more than half of the total Illinois population—have access to Great Lakes water even though they live outside the basin.

More than 130 years later, the diversion, which now accounts for an average of more than two billion gallons a day, remains controversial. According to waterwars.wordpress.com “A Brief History of the Chicago Diversion” posted in 2006, about 7 million people – more than half of the total Illinois population—have access to Great Lakes water even though they live outside the basin.

And diversion attempts continue, Smith warned. In the ‘80s and ‘90s, the drought-hit regions of the U.S. wanted to tap into this basin.

“There was never really a mechanism to protect against diversions, except for a little provision in the Water Resource Development Act that gave the U.S. government the power to veto diversion requests.

Smith says that isn’t good enough, citing a decision in 1998 by Canadian authorities to allow a company to ship tanker loads of water from Lake Superior to Asia.

And while the province of Ontario ultimately withdrew the permit, “the U.S. didn’t find out until after the permit was granted,” said Smith. “It caused a huge uproar.”

Smith said what did occur was action taken to prevent any future diversions.

“It really raised the issue of diversion again and as a result all the Great Lakes states and provinces got together to find a way to prevent this. It is not just for industry and municipalities and farms. It is part of who we are.”

States and businesses came together, realizing the common interest in protecting the resource. The result was the Compact, which is a legally binding agreement, not a treaty, on how to protect and manage the water resource.

“That was five years ago. Now we have to go back and implement it,” said Smith.

But while Michigan is ahead of the game, with 95 percent of trout streams protected from diversion, others, like the state of Ohio, seem to be going in the opposite direction.

Smith said Ohio is interpreting the impact of withdrawals from rivers on Lake Erie, rather than the impact on the river. “You can take up to a million gallons a day without a permit in Ohio from the Cuyahoga. In Minnesota, it is 10,000 gallons or more. So it really varies how states are implementing the compact.”

Why it matters to business

Businesses need water – and breweries need lots of water. For one reason, 90 percent of beer is water. For another, states and provinces in the basin must present plans annually in December showing how they are preserving and protecting the water of the basin. Those plans affect business policy and procedures on water usage.

Dave Engbers of Grand Rapids-based Founders Brewing Co. put it this way at the conference held at the Robert C. Pew campus of Grand Valley State University: “We are major influencers. Be activists. We can’t brew the great beer that we do without great water.”

Dave Engbers of Grand Rapids-based Founders Brewing Co. put it this way at the conference held at the Robert C. Pew campus of Grand Valley State University: “We are major influencers. Be activists. We can’t brew the great beer that we do without great water.”

Now, because of the Great Lakes Compact, anyone outside the basin seeking to obtain a diversion permit has to meet strict requirements, including:

• A determination of the actual need;

• Justification for how much water will be used;

• Complying with all conservations standards in the state and the Compact; and

• A commitment to return the water to the basin, less consumptive use.

All the states and provinces then vote on whether to approve or deny the diversion request.

The Waukesha case

In what is likely to become the blueprint for modern diversions from the basin, Wisconsin’s Waukesha County is requesting it be allowed to take 15 million gallons a day from Lake Michigan.

The county, which straddles the Great Lakes divide, is under a federal mandate to find a new water source, a key reason being they have drilled so deep that their supply is threatened by radium. To date, they have spent $8 million in studies and application fees, Smith said.

“This is the first application for diversion under the Compact. It will become a gold standard for diversions. It has to be done right. Everyone is looking at it.”

Given that the Compact and associated processes are in their infancy, some rules on water conservancy are at this point voluntary. But that may change, Smith said.

Given that the Compact and associated processes are in their infancy, some rules on water conservancy are at this point voluntary. But that may change, Smith said.

“Why is this important to you as craft brewers? You need clean water. You need a sustainable source for that water. It is integral to your industry,” said Smith in his comments. “I encourage you to work with the Council of Great Lakes Industries. They have studies showing how to reduce the amount of water used by the water intensive industries, reduce the time and energy spent on it and the money. That means something to you guys.”

Brewers, he said, can be “incredible” advocates. “You have a role to play. Create relationships with your state agencies. Encourage them to work on water conservation. Give them ideas on how to protect and conserve water, because these agencies are making decisions that affect a resource that is integral to your industry.”

Roger Eberhardt, senior environmental specialist with Michigan’s Department of Environmental Office of the Great Lakes, said the annual report was still being drafted. He referred to the “2013 Michigan Water Conservation Efficiency Program Review” as a resource for businesses. “It is a good source of information for Michigan and it is the main thing we do for reporting in the Compact process. I don’t know that it will change all that much for 2014.”

Eberhardt said the DEQ website provides water withdrawal assessment tools, and information on large quantity withdrawals, health department, permitting and more.

“The state of Michigan views the Compact as a very positive thing for Great Lakes Basin in general. It is important for the entire region to pay attention to how water is used and where it goes. The states are taking it seriously,” he said.

Is there a way to enforce Compact standards?

There is accountability, Smith added after his panel discussion. “The Compact is designed to allow citizens to legally challenge if they see water use or a decision that is not consistent with the compact. There is that legal hook. Also on the state level, if Michigan does not think Ohio is doing its job, for example, they can call the question and require Ohio to report out. It raises that peer-to-peer accountability.”

Brewers Association

Brewers Association Technical Coordinator Chuck Skypeck told the conference that the nationwide organization is moving forward with more sustainability practices, manuals and training in 2015. One project being considered is dashboard software that will allow brewers to track and quantify how water is used in craft brewery operations.

He emphasized that water costs and treatment represent a major portion of inquiries he gets at the association. “Whether it is from brewers in planning or municipal waste treatment representatives, usage of water and waste water is becoming a bigger issue all across the country. Things are changing so rapidly there,” he said.

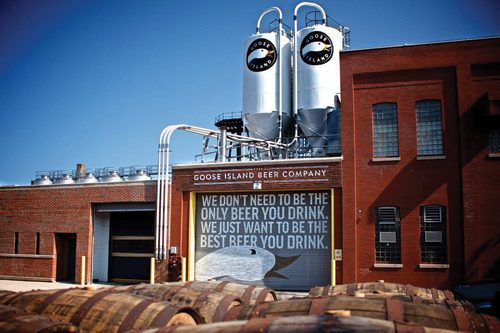

The Goose Island Story

Goose Island Brewery in Chicago, which produces about 100,000 barrels of beer annually with roughly 32 fermenters, once discharged spent yeast at a cost of about $250,000 in meter charges, along with spent yeast fees that included charges for biological oxygen demand (BOD) and total suspended demand (TSS).

That totaled some 200,000 gallons a year of spent yeast going down the drain.

“So where does our waste water go?” asked Ian Hughes, assistant manager at the brewery. “We’d love to do pretreatment, but don’t have the physical footprint for it. We are trapped in downtown Chicago, absolutely no room for any of that.”

Goose Island used sustainability manuals published by the Brewers Association to help solve the problem.

dramatic changes to the way it manages its waste water by teaming up with a producer of ethanol.

“Think of your brewery as a watershed,” he explained. “Look upstream, everything drains into one central point, which is your discharge.

“So what were we going to do with it? Hauling liquid waste, or ‘tankering,’ is very expensive,” he said. “A local bakery was excited about using it, but only wanted five gallons a month—not very helpful. We looked at adding it to spent grains for feed grain, but unfortunately too much liquid. One farmer wanted to land apply it, but we still had to tanker it.”

Goose Island found a solution through Iroquois Bio Energy Corp., a Rensselaer, Ind.-based ethanol producer, which given just 48-72 hours notice, will come out with its own tankers to take Goose Island’s effluent.

“So somewhere our spent yeast is powering vehicles, which is pretty exciting,” said Hughes. “It’s been a really great partnership.”

In 2013, Goose Island sent 16 tanker loads (about 100,000 gallons) to Iroquois – a reduction of about 83,000 pounds BOD and 62,000 pounds TSS. The amounts, said Hughes, are “a huge deal for us” – saving the brewery about $30,000. By November, they’d already sent 17 tanker loads.

Changes for Bell’s Brewery

The cost of water use and brewery effluent hit the wall in 2012 for regional craft brewer Bell’s Brewery Inc. in Galesburg, Mich. That was the year the city of Kalamazoo began to charge industrial rates. In 2013, the brewery used 38 million gallons of water. Of that total, 30 million was waste water or effluent; 7 million was beer, explained Walker Modic, sustainability specialist for Bell’s.

In 2012, the per-barrel cost of water, intake and discharge, went from 60 cents to $2.94 per barrel when the city began charging the industrial fee structure. In 2013, the cost averaged about $2.22 per barrel, totaling $551,000 based on that year’s production of 248,000 barrels.

The change in costs put renewed emphasis on recovering costs from the effluent, and taking a closer look at the contents rather than the volume. At that time, Bell’s already had a sustainability program in place.

In December, Bell’s will put its 120,000-150,000 gallon per day treatment facility online. It is designed to convert brewery effluent into biogas (principally methane), which will then be combusted to power a 150-kilowatt engine for electricity. Heat generated from the process will be captured for use in brewery operations.

“It is pretty significant,” said Modic, who has worked at Bell’s since 2012. “We took it on knowing it would probably have a greater than seven year return on investment, including tax credits associated with green energy production. We are getting our feet wet with renewable energy.”

Modic pointed out the great value of water security and water prices in the Great Lakes basin, with tap water costing about a quarter cent per gallon. In a study conducted by Circleofblue.org, average municipal water costs ranged across the country from just less than a quarter cent per gallon to a penny per gallon. The study also showed that a family of four in Phoenix paid $34 per month, while the same family living in the Detroit-Chicago-Milwaukee area would have paid about $26 per month on average.

Modic observed that many brewers are opening new facilities in the basin and eastern U.S.

Sierra Nevada, a brewery with headquarters in Chico, Calif., and New Belgium, which is based in Fort Collins, Col., are two examples of firms that have opened operations in Asheville, N.C.

Another brewer heading east is Escondido, Calif.-based Stone Brewing Co., which has announced plans for a plant in Richmond, Va.

For California brewers, it is a situation of “absolute unavailability,” with an 8 million gallon cap on water purchases.

For California brewers, it is a situation of “absolute unavailability,” with an 8 million gallon cap on water purchases.

And California is home to more than 400 craft brewers, the most in the nation.

Modic advised that brewers should have a strategy in place to address water costs in the future. Brewers need to be prepared by using world-class water efficiency practices, and/or use risk assessments to determine what they would be willing to pay for water security and invest in water efficiency projects accordingly.