After he injured his foot at work, Mr. Hernandez sought medical attention. Though he speaks English, Hernandez’s first language is Spanish. Realizing that Hernandez was most comfortable with Spanish, the orthopedist asked every question in both languages. However, the written discharge instructions were provided only in English. Those instructions directed Hernandez to follow up with the orthopedist within 24 hours. He did not. Eventually, Hernandez’s foot injury led to the amputation of his lower leg.

Hernandez filed a lawsuit claiming that the amputation was the result of his physician’s negligence. The physician argued that the fault was with Hernandez for not following the discharge instructions. The court ruled in favor of Hernandez, and the insurance carrier paid $46,500 in legal fees.

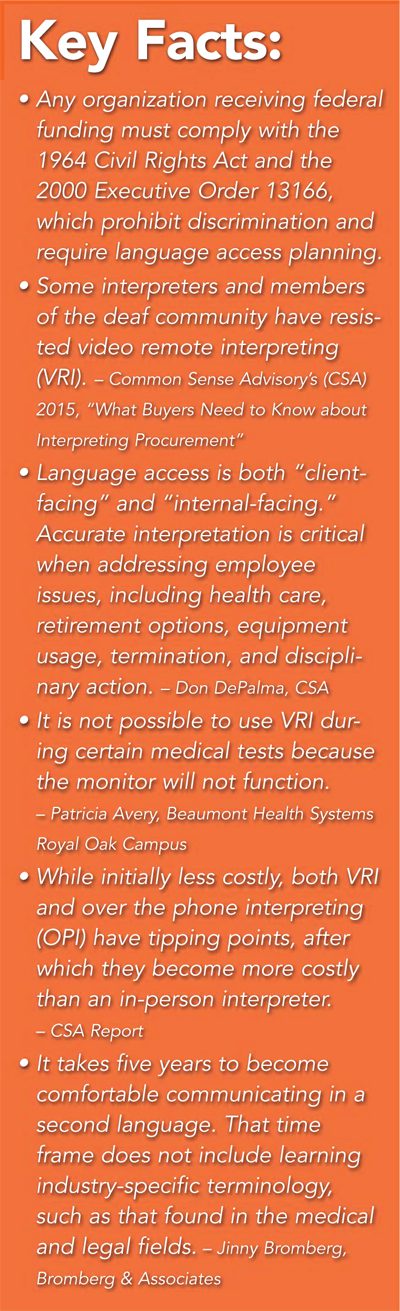

This case and several others are detailed in the University of California-Berkeley’s 2010 report, “The High Costs of Language Barriers in Medical Malpractice.” Those costs are steepest in the health care industry where lives can be lost. But, companies across all industries can benefit from language access planning.

Non-English speakers are a growing force of customers, employees, and business partners. According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2011 American Community Survey, 21 percent of people at least 5 years of age speak a language other than English at home.

This percentage has consistently increased since 1890 when it was first recorded. And the bureau expects the trend to continue. If companies do not plan for language access, they risk breeching confidentiality, alienating customers, and forfeiting new business and talent markets.

Qualified interpreters

According to the UC-Berkeley report, Hernandez’s physician and medical assistant testified that they knew Spanish “well enough’” to communicate with their patients. But speaking a language is not the same as interpreting. That mistake can be damaging to both the client and the company, says certified interpreter Jinny Bromberg.

“For a long time, being bilingual was associated with being capable of being a translator,” says Bromberg, who founded Hamtramck, Mich.-based Bromberg & Associates in 1999. “But that’s not the case. Being bilingual is a mandatory requirement, but it’s just one part of it.”

Bromberg says, at a minimum, qualified language professionals should have proficiency in at least two languages, possess a thorough understanding of the code of ethics for their field, and be able to interpret consecutively and simultaneously, as well as perform sight translation.

Patricia Avery manages the interpretive services program at the Royal Oak, Mich. campus of Beaumont Health System, which contracts with Bromberg & Associates as well as other providers.

But because there is no single certifying agency for medical interpreters, Avery said her team must do their own “due diligence.” In its contracts, Beaumont requires that interpreters have formal training in health care interpretation and at least two years of health care interpreting experience, a process that is less complicated when contracting for interpreters for the deaf and hearing impaired because the state of Michigan sets the certification standard.

Interpreter certifications are most common in the legal and medical fields, said Don DePalma, founder and chief strategist of Common Sense Advisory, a market research firm headquartered in Cambridge, Mass.

In those fields, said DePalma, federal regulations are driving the language service industry toward a common standard. In the corporate world, certifications are less common, but technical knowledge is just as critical, he said. You need someone who “speaks Corvette and Spanish,” said DePalma.

Translation technology

According to numbers provided by search giant Google just two years ago, its Google Translate online service processes some one billion translations per day for about 200 million users.

While the numbers may be higher, just how accurate the service may be is a running question.

Perhaps even more important is the question of confidentiality, says Rick Woyde, managing director of Language Arts & Science, a translation services and solution provider based in Royal Oak, Mich.

Indeed, with the Google terms of service contract stating that any data transmitted or translated via its applications falls within its domain to use as it wishes, that may be more of a statement than a question.

“Google Translate is a funnel to improve search results,” said Woyde. “Anything that we drop into Google Translate gives Google license to publish it in their search results.”

“Google Translate is a funnel to improve search results,” said Woyde. “Anything that we drop into Google Translate gives Google license to publish it in their search results.”

In other words, while the Google service may be fine for a letter from your grandmother, for confidential e-mails, legal contracts, and proprietary information, businesses should use a software that keeps data out of the public domain, said Woyde.

Yet, when Woyde surveyed his clients he found that many of them used Google Translate to handle smaller translation tasks not contracted out to firms like his. His response to what he felt was a growing issue is Pairaphrase, a service the firm launched in 2014 to keep a company’s sensitive translations confidential.

As Pairaphrase is used, it gets smarter, increasing its accuracy with the help of human translators, said Woyde.

This point gets to the other finding in his client research, which is that many companies are using internal bilingual staff as translators.

From a company’s perspective, internal staff may have many of the skills needed, including knowledge of the language and specific insight into the market and the industry served, especially when compared with an external supplier.

Woyde said that while having someone do the work may save money, it largely ignores the potential costs related to translation errors, employee stress, displaced workloads, and time lost on “real” jobs.

Although hiring qualified translators may not be a cost-effective solution for these companies, Pairaphrase could be, with the ability to speed translation time by up to 75 percent—meaning a job that may have taken eight hours, takes only two to three hours with Pairaphrase.

VRI: On-demand and visual

Another approach is with the use of video remote interpreting (VRI), defined as real-time, human interpreting using an Internet connection, webcam, and microphone.

Combining the on-demand feature of over the phone interpreting (OPI) with the visual cues of in-person interpretation, video remote interpreting is often cheaper than in-person interpreting.

However, without the proper technology, VRI is more expensive than OPI, according to a report from Common Sense Advisory. “What Buyers Need to Know about Interpreting Procurement” says while VRI makes up the smallest share of that market, its share is expected to increase as companies continue to integrate mobile technology into their business practices and look for ways to reduce language access costs.

Beaumont’s Avery says VRI has made a big difference since the organization began researching the technology in 2009, as part of its participation in a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation initiative.

By 2011, Beaumont had launched its VRI service, although Avery said the hospital also uses in-person and OPI for longer interactions and sensitive discussions such as those involving end of life care.

Cultural competency

Language is one piece of the larger puzzle of cultural competency, that “set of behaviors,

policies, and attitudes that form a system or agency that allows cross-cultural groups to effectively work professionally in situations,” states BusinessDictionary.com. Bridging the cultural divide can be more daunting than overcoming language barriers. Several sources pointed out how culture informs people’s views on life and death, how they look for a job, how they interact with the opposite gender, and even how they view interpreters.

Creating understanding between people of different cultures is the mission of Welcoming Michigan, a program of the Michigan Immigrant Rights Center that works with U.S. businesses, government entities, and neighborhoods to help create communities that embrace immigrants.

To this end, Welcoming Michigan assists companies with language access planning, sponsors community cross-cultural encounters, and educates business owners on the immigrant experience, said Christine Sauve and Jonathan Romero, who serve as program coordinators.

As globalization increases, organizations are restructuring to be more multicultural accessible, said Romero, who says some organizations struggle to integrate cultural competency into a business.

With a mission of transcending “linguistic and cultural barriers, bringing people and businesses closer together,” Jinny Bromberg says her company, already a provider of in-person cultural awareness training, is now developing an online library of cultural awareness trainings that will be categorized by country as well as industry.

“What we do is really connecting people on such a different level,” said Bromberg. “Culture and language are at the core of our beings, and the opportunity to help people embrace them and eliminate the cultural and linguistic divides is really exciting for me.”