Across the nation, thousands of pork producers typically have, in their state or very near by, a facility they can transport their animals to for processing, an obviously key link in a chain that ends with customers selecting product from their grocery shelves or a restaurant patron ordering from the menu.

The industry, as large as it is, isn’t without its gaps, but the market has its way of identifying those and, as supply and demand economics kick in, adjusting along the way.

Sometimes, however, it takes more than a few years to make those adjustments.

Such was the case when Thorn Apple Valley Farms closed a key facility in Michigan, resulting in producers having to truck their hogs to facilities in Indiana, Ohio and Kentucky, adding time and dollars to the literal food chain.

It wasn’t until 2013 that producers, armed with a $100,000 state of Michigan grant, were able to do something about this particular gap, identified as such by Gov. Rick Snyder in his first State of the State speech a year earlier.

The money was to be used to explore the feasibility of a production facility in the state and one of the people the producers reached out to was Doug Clemens, CEO of Clemens Food Group, a Pennsylvania-based family owned business that producers in Michigan had dealt with in the past.

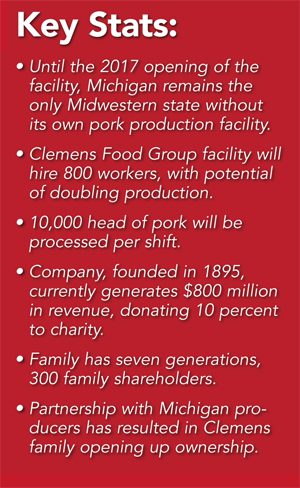

Clemens, a fourth generation member of the family, is telling the story from a construction trailer in Coldwater, Mich., on the site of a 450-acre, $255-million facility that will process some 10,000 pigs in a single shift when it opens in mid-2017.

“We were passively looking at expanding,” says Clemens, recalling those first discussions. “At the same time, we had relationships with some of the producers from about 25 years ago, so they were familiar to us and they knew us as well, which is why we were initially approached.”

Some 800 people will earn wages starting at about $14 an hour for production jobs, with higher paying $20-$30 per hour wages for technical and trades positions, but that number would double should Clemens decide to spend another $30 to $40 million on putting in a second shift.

How it came about

This is certainly a complex story, and not just because of the plant itself, the first greenfield project the company has undertaken since it was founded in 1895 by John C. Clemens, a Mennonite farmer whose Pleasant Valley Packing Co. was based in Mainland, Pa.

When that plant burned down in 1946, the family, unable to secure steel to rebuild since war rations were still in effect, negotiated with the owners of Hatfield Quality Meats in nearby Hatfield, Pa., where Clemens Food Group remains today, employing 2,200 in an operation that includes raising and slaughtering hogs, as well marketing under several brands.

Doug Clemens, who spends about half his time hopping back and forth from Pennsylvania to Coldwater (the company just bought its own plane to shorten what would otherwise be a 10-hour one-way trip by car or commercial carrier), continues the back story of how the plant came to be.

Discussions with farmers eventually morphed into an arrangement involving an equity investment in the company, the first time anyone other than a family member has become an owner.

“It’s way more than a supplier relationship,” says Doug Clemens. “There’s a co-dependency with us and we both recognize that we are interested in sustaining the business in a way that cascades from generation to generation. We’ve been very deliberate in maintaining and building those relationships.”

The company was also somewhat picky in who it invited to participate, a careful widening of a relationship that had its genesis in various transactions conducted years ago and after reputations were earned.

“The original group had come to us and they had done their research on us,” said Dan Groff, Clemens’ director of Ag Business Development, who has been with the company since earning degrees from Messiah College and St. Joseph’s University.

For Doug Clemens, plans to become a veterinarian eventually shifted instead to animal science and his graduation from West Virginia University. Rather than working somewhere else (now a requirement of family members wanting to be in the business) he answered the call of his father, now 86, who wanted to know when he was going to be coming back to work.

Clemens did just that, working in livestock procurement for 15 years, then managing the company’s fresh pork operations and later business development and the firm’s research and development operations.

Then one day, the company’s president, who was also his cousin, told him he was going to be vice president of Strategic Planning.

“Neither one of us knew what strategic planning really meant, but we knew that we needed it, so I sunk my teeth into that,” says Clemens.

Part of that included having discussions with people like John L. Ward, clinical professor of Family Enterprise at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University, and the establishment in 2000 of what is being called a “trust triangle” that includes the company’s board of directors, management and family.

“Each of those groups has its own responsibilities and that’s how the business is structured,” says Clemens, who was elected to the board of the Clemens Family Corp. in 2014.

Being able to tap into the expertise that is represented on the board of directors (all of whom, other than Doug Clemens and a son-in-law, are outside the family) was seen to be critical to the success of the Coldwater project.

“We were adamant about seeking opinions from people on the board who had done things like this before,” says Clemens. “And we weren’t just putting up a building, we were building a market.”

That plays out in the fact that even today, months before product is shipped from the Coldwater plant, Hatfield-branded product is being sold in area stores.

But it’s the relationships with the state’s pork producers—the farmers, many of them family businesses—that have become a central strength of the Clemens Food Group and its operations.

Part of that is recognizing the alignment of interests that exists, something that has found its way into discussions with producers, says Groff, who is responsible for negotiating contracts with area farmers.

Part of that is recognizing the alignment of interests that exists, something that has found its way into discussions with producers, says Groff, who is responsible for negotiating contracts with area farmers.

“We have an interest in hog production ourselves so we understand the needs of the producer and our agreements reflect that,” adds Groff, referring to the 55,000 sows Clemens has in its operations, about half of what is needed for the Hatfield operation. That translates into just under 1 million pigs a year.

For Coldwater, about 90 percent of the pigs needed for the first shift have already been secured, with the balance to come from spot buys and future agreements.

The argument for aligning with a coordinated operation like Clemens also comes in the form of a value equation, with an established brand in the market and the benefit of producers being able to see more value derived from their hogs.

“If we were just to sell fresh pork, the margins are slim,” says Groff.

One of the members of the group Clemens has partnered with is Fred Walcott of Valley View Pork, based in Allendale, Mich.

“With only a limited amount of processing in the state of Michigan and good [hog-raising] operations of substantial size, a lot of the hogs have been going to processing plants in Indiana, Kentucky, Pennsylvania, Ohio and Illinois,” says Walcott. “It became obvious it was time for Michigan to take a serious look at the possibility of keeping those hogs right here.”

Eventually, what had started out as a “go on their own” proposition for producers became the partnership Doug Clemens has described, albeit without any disclosure of specifics. “It was a minimum investment,” he says. “But they have skin in the game along with their commitment for supply. That’s what really makes it work.”

State, region are invested

From a government participation standpoint, the Michigan Strategic Fund provided $12.5 million in Community Block Grant funds for infrastructure improvements, land acquisition, workforce development and on-the-job training for the plant.

“This decision by the Clemens family only underscores that Michigan’s food and agriculture sector is ripe for innovative business opportunity, economic development, and new jobs. It’s a growing industry and we’re excited to have a pork processing plant back in the Great Lakes State,” said Jamie Clover Adams, director of the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development. “The project further highlights the commitment and partnership by local and state officials, economic development groups and private industry to bring new companies and investment into Michigan.”

A package totaling some $55 million includes nearly $16 million in tax savings that have come in the form of personal property tax reforms.

Paul Beckhusen, president of the Economic Growth Alliance for Branch County (where Coldwater is located), said the addition of the company to the community “exemplifies our vision and illustrates the positive direction in which we continue to lead. This project has been a template of success for state, regional, local and private partnerships—all working together to attract an ideal corporate citizen like the Clemens Food Group.”

Clearly, things like location of highways was critical to the decision to pick Coldwater, located on I-69 and near I-80 and I-94.

While the formal relationship with producer families and Clemens wasn’t facilitated by the state, there was what Doug Clemens calls an unprecedented level of cooperation between the state, county and city when it came to making the project a reality.

“I’ve never seen that kind of cooperation before,” he said. “People usually have their own agenda, but in this case, they had one agenda and that was to make it work for us. We’ve been extremely happy to work with all levels of government on this project. They were very proactive.”

Lisa Miller, who until June 2016 was executive director of the Branch County Economic Growth Alliance, called the Clemens move “a home run for us.”

Up until now, the largest local private employers have been a Wal-Mart distribution center with 1,000 workers and Asama Coldwater Manufacturing, which employs 400 in the making of brakes for Honda vehicles.

Clearly, things are progressing well as far as construction is concerned, as well as the myriad of details that will take place before the first product is shipped the day after Labor Day.

Included in that long list are the hiring and training of workers (some are now being trained at the facility in Pennsylvania). About a year ago, Earnie Meily, the company’s human resources manager in Hatfield, relocated to Coldwater, where he continues to develop local relationships, including those with Kellogg Community College, where specialized training programs will provide the workers needed on an ongoing basis by the company.

Clemens expects Gray Construction, the contractor that is building the facility, to hand over the keys on May 1, with a ribbon cutting ceremony to take place on July 29.

But getting most of the facility’s 640,000 square feet fully refrigerated is a process that will take weeks if not months to accomplish. It will also take time to gradually ramp up production to the 10,000 head of pork a one-shift operation will handle.

Even then, a significant portion of what is produced in Coldwater will find its way back to the east coast, where the Hatfield name, the signature brand along with several other specialty labels, is marketed.

Environmental impact

In any project of this size, environmental considerations come well ahead of any shovel in the ground.

At Clemens, that task befalls William Fink, the company’s environmental management specialist, who turned to Fishbeck, Thompson, Carr & Huber Inc., a consulting company that includes environmental work in its portfolio, to manage the approvals at the local and state level.

Focused on everything from mitigating things like soil erosion that might be impacted during construction, to managing storm water—typically rain that falls on buildings and elsewhere—officials sifted through how Clemens intended to proceed with the project.

Permitting for the facility included a detailed analysis of every aspect of the operation, including the projected emissions resulting from natural gas boilers.

Perhaps surprisingly, very little of the hogs is discarded, with everything from the meat to what some might think of as waste being converted into product that is sold—even if that includes fertilizer sold to farm operations.

In the end, attention to resources like water—in the case of Clemens’ operation, much of it reclaimed, cleaned and reused—is included in the environmental permitting process.

“We’ll have a facility where process water, including that used to clean trailers, is treated before ultimately being discharged to the city of Coldwater,” said Fink, who added that minimizing the amount of waste is central to the company’s strategy. “Our plans are to recycle as much as possible.”

In its application to the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality, Clemens’ consultants pointed to the design of the state-of-the-art facility as one that was “subject to the same high levels of cleanliness as the meat packaging industry, greatly reducing the potential for odors.”

Family and business

At Clemens Food Group there are some 300 family shareholders out of a total of 700 family members, with the seventh generation just recently born. Primarily, members of the fourth and fifth generation are managing the company.

Getting along with the family is something, says Doug Clemens, that came from the deliberate decision to separate family from business.

Getting along with the family is something, says Doug Clemens, that came from the deliberate decision to separate family from business.

“If you were to be interviewing one of my nephews, he would tell you if he wasn’t performing in the job, I would be the first to be at his house, consoling him on the loss of his job.”

Clemens, as part of his earlier strategic planning role, became determined not to see the family business fall prey to a sobering statistic: that 97 percent of family enterprises cease to exist after the third generation. “We made that a conscious decision and we’re adamant that the responsibility to continue is for generations to come. Stewardship is one of our core values.”

The company, with roots in the Mennonite faith, also adopted a value of generosity, with 10 percent of pre-tax profits going to charity.

And while Clemens himself has worked nowhere other than the business, he has at least one child who will work somewhere else to get the “outside” experience before taking on a management role.

“We do strongly recommend that family members work elsewhere for about five years,” says Clemens. “It’s a matter of having the diversity of experience, which we think is important.”