It’s not what globalization will do for your business,” says Jeff Jorge, “it’s what it will do to it.”

Jorge spoke recently at a seminar held at Warren-based Technology Ventures Inc. (TVI). The event’s goal was to educate Macomb County companies about Foreign Trade Zones and the ease of exporting through just such a designation.

TVI operates under the authority of a larger Foreign Trade Zone (FTZ) that is formally set up as the Greater Detroit Foreign-Trade Zone, Inc. (GDFTZ), a nonprofit Michigan corporation that was granted its status by the U.S. Commerce Department in 1981.

Statewide there are eight FTZs and nearly 300 across the nation.

While TVI is not in itself a FTZ (there are at least 20 operators throughout the Metro Detroit area), it is marketing itself as a “go-to” place for companies wishing to take advantage of the system, which has its roots in the Foreign-Trade Zones Act of 1934. The legislation was intended to mitigate some of the destructive effects of the Smoot-Hawley Tariffs of 1930 and “expedite and encourage foreign commerce” in the U.S.

While through World War II, manufacturing activity was allowed only on a very limited basis, in 1950, the original act was amended to open up FTZs to manufacturing.

Still, it wasn’t until 1980 that Congress amended the Act so that products manufactured in the zones would not be subject to a tax until all its parts were assembled and then sold. This ensured that the only tariffs a producer inside the zone selling to U.S. customers would pay, would be on the raw materials imported into the zone. This “integrated” model, which replaced the previous “island” model, spurred growth in the U.S. foreign-trade zones program.

Jorge is something of an export success story himself. Born and raised in Brazil, he started working full-time at 16 to help his family, but ended up getting the lesson that would direct the rest of his far-reaching business life. Employed by an international trade company at that young age, he “saw early on first-hand how products were coming in and out of the Brazilian border, how they would get stuck at customs, why they were sent back,” he recalls.

His career has taken him around the world in business. Now a principal of Baker Tilly, Jorge serves as practice leader for the firm’s international service in Michigan as well as Latin American services desk leader for the entire firm.

He joined Baker Tilly a year ago after his firm, Global Development Partners, merged with the full-service accounting and advisory firm.

Jorge’s entire raison d’etre is to help people create strategies for, and understanding of, how to achieve business success in foreign markets. How to, in short, “ride the tide” of import-export to greater business success. In fact, Global Development Partners grew out of Jorge’s MBA thesis, which focused on how to help companies go abroad.

Jorge’s entire raison d’etre is to help people create strategies for, and understanding of, how to achieve business success in foreign markets. How to, in short, “ride the tide” of import-export to greater business success. In fact, Global Development Partners grew out of Jorge’s MBA thesis, which focused on how to help companies go abroad.

“You need to drive what you want to happen for your business,” he says.

“There are three modes into which any company falls when they try to go abroad: the ‘haven’t-beens,’ the ‘once-bittens’ and the mature groups that have been operating abroad, but have specific issues they need to address,” notes Jorge. “The first two groups start cobbling together something from this person or that and the result is typically not great. They’re trying to do something they’ve never done, with no experience, stringing a necklace of pearls that they don’t know how to put together.”

In short, they need help. It’s a good thing such help isn’t hard to find.

Foreign Trade by the Numbers

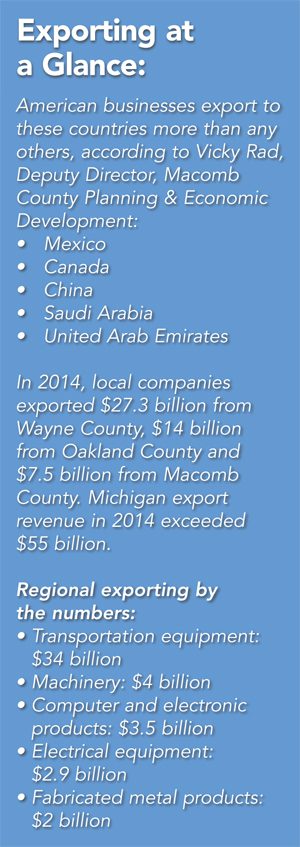

Perhaps that’s why less than 1 percent of American businesses export or participate in some type of international trade. The average for developed countries, says Jorge, is 8 percent.

What’s more, close to 60 percent of the less than 1 percent who do engage in export activities, do business in only one foreign country, mostly Mexico or Canada, Jorge notes. That may be because they have all the business they can handle on local soil – or it may be that they haven’t a clue where to begin with doing business abroad.

There are 18,000 businesses in Macomb County alone and slightly more than 850,000 firms in the state with fewer than 500 employees. Nationwide, that number bumps up to some 30 million companies, which means that stepping foot onto foreign soil is sure to yield some sort of growth.

Jorge delivered his talk as part of a series of speakers in the upper level conference room of TVI’s 6.5-acre, 78,000-square-foot facility at 10 Mile and Groesbeck. It looks very much like any other warehouse you might see in town, but actually offers the special privileges that come with doing business on foreign soil.

Except it’s in Macomb County.

That’s part of what makes an FTZ so special for businesses. Most people don’t know they have one in their own backyard, let alone how it can benefit what they do or make it easier, which is why TVI hosted the event, says Axel Cooley, the company’s director of business development.

“Exporting can be a lot easier than it sounds,” says Cooley. “A Foreign Trade Zone is a government-designated facility to make it as easy as possible.”

There are five other FTZs besides TVI operating in Macomb County, the newest being Transpak, Inc. in Sterling Heights.

Understanding Foreign Trade Zones

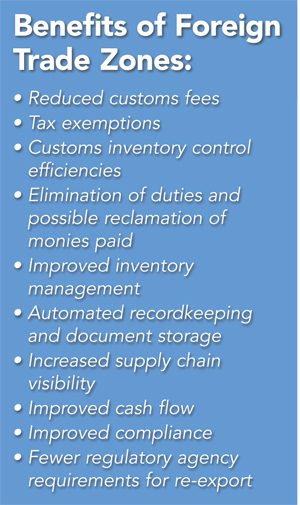

Business that is conducted under the status of an FTZ is considered by the U.S. Customs and Border Protection as if it occurred outside the U.S., which means the FTZ (and operators like TVI) can offer significant savings on import duties for both components and consumer-ready merchandise, among many other benefits.

Some companies go so far as to ship parts from abroad to an FTZ and have products assembled within the FTZ to avoid paying taxes or tariffs on each individual part, and that’s completely legal. It’s one reason FTZs were created, says Cooley.

But manufacturers actually get to choose based on whichever tariff is lower. This is because sometimes components used in manufacturing carry a higher rate than the end-product. Imported automobiles, as an example, have a duty rate of 2.5 percent but imported components have an average of 5-6 percent.

If an assembly plant operated as an FTZ, it would choose the duty rate that exists after a vehicle was produced, saving 2.5 percent or more.

FTZs are under the supervision of Customs as well as the U.S. Homeland Security Council.

Constance Blair, founder and president of TVI Logistics, says the majority of businesses a company like TVI is trying to attract are what she calls local economy businesses.

“When you start off in business, you look for the most efficient way to get your inventory,” says Blair. “But as you grow, the best way to increase your bottom line is to go directly to the source itself and cut out the middle man. Many people fear that would be a higher risk, but that’s not always true. Especially if they learn about a FTZ, they can buy the same product at a far better price with more control of their delivery schedule and type of inventory they can carry.”

Many businesses saw foreign trade as a lifeline during the recent recession. “With the economic downturn in 2008-2009, a lot of companies had to diversify,” says Vicky Rad, deputy director of Planning and Economic Development for Macomb County. “One of the markets they were looking at was the global market, exporting.”

Rad convened the recent seminar at TVI to give local companies “the resources they need to make that leap of faith that they’ll do alright in another market.”

What’s more, many companies are being acquired by a “foreign parent,” so understanding how to achieve transactional success abroad is a welcome skill, Rad notes.

What It Takes to Export

If a product or service is unique here, chances are good it will be unique in other countries, says David Newhouse, international trade development manager for the Michigan Economic Development Corporation.

“It’s one thing to make a good quality product. But what makes it more beneficial for exporting is if there’s some level of innovation, something that makes them stand out or stand apart from competitors that gives a great selling point. It’s not unique to any industry.”

While Michigan is known for manufacturing, says Newhouse, other industries are ripe for exporting, one example being IT services.

Macomb County has long been home to automotive suppliers and manufacturers, but two other big industries here are defense and aerospace, both of which can benefit from foreign trade.

In a 2012 article, Daniel Griswold, president of the National Association of Foreign-Trade Zones in Washington, D.C., attests that as much as the government “saved” the U.S. automotive industry several years back, FTZs had a lot do with it, too.

“In 2010, a total of 2,400 companies and 320,000 American workers made use of the FTZ program to manufacture, process and distribute a wide range of products, including … motor vehicles,” Griswold wrote. “The FTZ program puts U.S.-based auto plants on an equal footing with foreign producers by allowing them to source components internationally without paying the higher tariffs.”

More than 80 percent of the combined $45 billion in merchandise that flowed through FTZ-based auto plants in fiscal year 2010 was sourced from domestic commerce,” Griswold wrote. “As a sector, global automakers employed a total of 45,583 workers in FTZ subzones in 2010 in relatively well-paying jobs.”

Expanding into foreign markets was a saving grace for Newhouse when he was president of a manufacturing company in Ypsilanti. The economic downturn represented, he says, “our most successful years, because we diversified abroad and so half our business was export. We experienced record sales, record profits and there were very few manufacturing companies that could say that during the economic downtown.”

After retiring from that position, Newhouse stepped into his current one with the Michigan Economic Development Corporation, where he helps Michigan companies find the many resources offered by the MEDC to help them dip a toe in the waters of foreign trade.

The MEDC, which has offices in Canada, Mexico, the United Kingdom, Germany, Brazil and China, often does a form of “matchmaking” to connect U.S. companies with their foreign counterparts.

The MEDC, which has offices in Canada, Mexico, the United Kingdom, Germany, Brazil and China, often does a form of “matchmaking” to connect U.S. companies with their foreign counterparts.

In order to be an economic superpower, Newhouse says, “it’s very important to have a presence abroad. As long as you remain competitive from a global standpoint, you’re also strong on the home market, too.”

Competition forces innovation, says Newhouse. “To continue to be innovative, we have to be aware of what’s going on in the world. You have to be a world player. If you don’t continually innovate and you’re selling yesterday’s product, you’re not going to be in business for the long-haul.”

Using an FTZ, says Jorge, makes foreign trade “less lonely and probably less scary. If you think about how markets connect, an FTZ can be an element of your success abroad because it can connect dots and help you approach markets as a collection of ecosystems.”

Trust is also a key ingredient, says Newhouse. “In order to be successful in exporting, you have to establish an excellent personal relationship — it is all based on building trust between you and the company abroad with whom you’re doing business. A good business relationship comes from a good personal relationship.”

In the end, while there are systems in place to guide and ease the process of foreign trade, it often comes down to who you know and how you work those relationships. And there are plenty of local tools to get you started.