Everyone has at least one or more dates that stand out in their lives, points on the calendar that they can look back to, some with delight, others not so much.

Everyone has at least one or more dates that stand out in their lives, points on the calendar that they can look back to, some with delight, others not so much.

In America, one of those days is, of course, Sept. 11, 2001, the day terrorist skyjackers took down the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center and crashed into the Pentagon, killing thousands in the process.

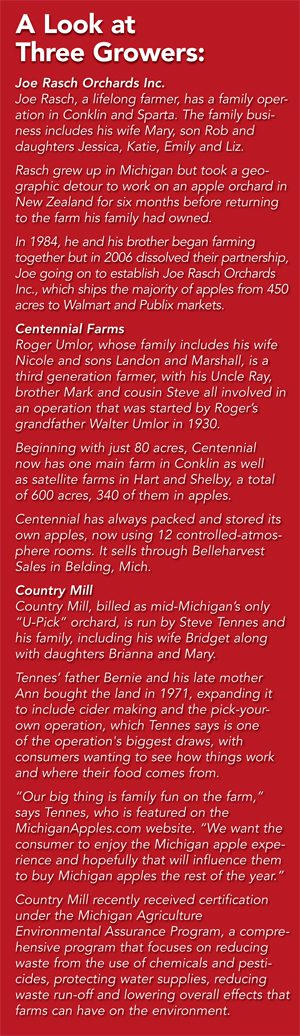

For Diane Smith, who runs the Michigan Apple Committee, there’s yet another date that stands out—certainly not as quintessential as 9/11 but at least for the members of the quasi-governmental industry group she heads, if not life-changing, certainly momentous in its own right.

That day, April 27, 2012, was when Michigan effectively lost its apple crop for the entire season.

“We had very warm temperatures in March,” recalls Smith, now a 19-year veteran of the group representing some 850 apple producers that grow what Smith refers to as “America’s favorite fruit,” (she began shortly after graduating from college, working her way up through the organization). “Those warm temperatures caused the trees to wake up, blossoming early. Then we had a series of freeze and frost events, which was very bad news.”

While growers did all they could to deal with the weather, including using big fans to shift the air between rows of trees, in the end it simply wasn’t enough.

“When the freeze came, that was pretty much the end,” says Smith. “We lost 90 percent of our crop.”

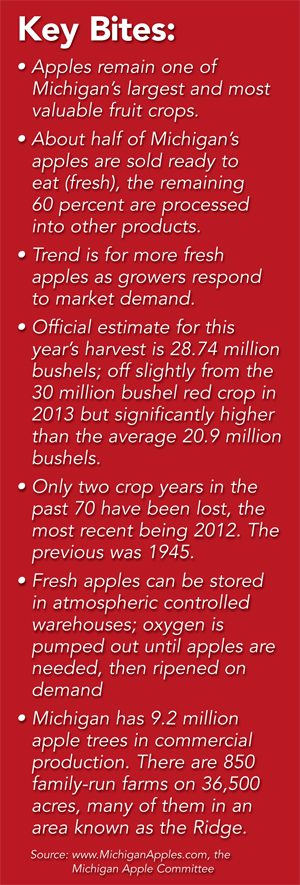

It had been 67 years – 1945 – since the last time Michigan growers had experienced such a loss, somewhat remarkable given the fact that we’re talking about a natural product that depends on the vagaries of weather.

Fast forward to 2014 and we see a forecast that comes very close to the record 30 million bushels apple growers harvested in 2013, this year’s estimate being 28.74 million bushels as of late August. A “normal” year? About 19.7 million bushels – some 828 million pounds of fruit.

Those numbers put Michigan third in the nation, behind only Washington and New York and ahead of fifth-place California and even Oregon, just south of first-place Washington state.

And while in some respects, it may have been the devastation of 2012 that’s partly responsible for record harvests now being experienced, so is the investment in different ways of growing and, in classic business practice, listening to your customer.

“Growers invested back in the business that year, spending the time they might otherwise have spent in the orchards tending to the trees and, of course, harvesting in the fall,” says Smith. “They did things that they wouldn’t normally have time to do, which was very inspiring really. Others might have just curled up, but our apple growers are a resilient bunch.”

They are also highly connected to the supply chain, which includes the fresh apple shipper, who represents the sales organization for their fruit.

The shippers, who sell to stores, are, in turn, listening to what those outlets are hearing from the end consumer. What sells. What doesn’t. What the trends in fresh fruit are at a retail level.

So what do the growers do with that information?

So what do the growers do with that information?

For starters, it affects the choices they make when it comes to buying the trees that won’t actually go into the ground for three years, buying these from nurseries – some in Michigan, others in New York, Washington state and elsewhere.

More per acre

Part of the role Smith and her team at Michigan Apples have is to supply the growers with the vital market studies that will drive those decisions.

But there’s something else going on that is driving record production. Coincident with recent trends, but not necessarily entirely linked to the crop loss, apple growers are trending toward higher density growing operations.

“In the past, growers commonly planted about 400 trees per acre,” notes Smith. “Today, with trestle systems, there can be up to 2,000 trees on the same amount of land.”

In that method of growing, the trees are effectively “trained” to grow in a certain direction, making the job of harvesting that much easier.

That comes back to benefit growers in very tangible ways, especially since the challenge of finding reliable, trained harvest workers remains one of the most significant obstacles faced by Michigan growers.

“Securing the seasonal labor needed to harvest a crop (from mid to late August through to about Halloween) is probably the one thing that keeps them up at night,” says Smith.

The tending of the crop and ultimate harvesting, she adds, is not typically the kind of work that the average person is going to want to do. “I know I wouldn’t be able to do it,” quips Smith. “It’s physically demanding and intense.”

It’s one key reason that growers are often looking beyond the U.S. border for help when that busy harvest time comes, in most cases to countries where Spanish is the dominant language.

When they do, they’re often swimming in a seasonal labor pool that runs deep, often with generations of worker families, although Smith does point out that some younger members of those families are choosing other paths, likely at least in part due to competition created by auto industry growth in Mexico.

And then there are the inevitable employment regulations.

“Imagine a program that was written in the 1950s having to be implemented in today’s work environment,” says Smith. “And then add in the bureaucracy of the federal government to the mix.”

Still, the system is one that has done its necessary job – providing skilled hands that are essential to the lifecycle of the state’s apple industry.

operate Redpath Orchards, based in East Leland, Mich.

“This is a done-by-hand harvest,” notes Smith, pointing to something of a disconnect that exists among some members of the general public who might wonder why growers don’t just “add another machine” to help with the work.

“There’s definitely a skill involved,” says Smith. “The fact is the buds for next year’s apples are already on the trees and those who work in the orchards not only need to be able to recognize when an apple is ready to be picked, but to do so in a way that doesn’t affect next year’s crop. It’s about nurturing the trees.”

Adding to the dynamic are the inevitable thoughts that go through the minds of those who run a family business, in many cases one that is multi-generational: Will there, in fact, be a next generation to which to hand off.

“It’s something we talk about a lot,” says Smith. “There are a lot of sixth- and now seventh-generation growers where sons and daughters have gone to college and are returning with a desire to be part of the family business. And some of the younger people getting involved in the industry have never even been in growing before.”

The state’s stature as an apple producer can be tracked to a near-perfect combination of climate, soil and drainage, particularly noticeable in an eight-mile wide, 20-mile long swath of land covering some 158 square miles in portions of Kent, Newaygo, Muskegon, and Ottawa counties.

The “Ridge” is where deposits of fertile clay loam soils, with their excellent moisture holding qualities, plus elevations of more than 800 feet and proximity to Lake Michigan offer a micro-climate ideally suited for apple production.

“You get warm during the day and cool at night,” says Smith. “That helps create sugar content of apples and provides a better casing (the skin).”

Indeed, some 65 percent of apple production in the state comes from that area.

When the apples are ready for harvest, about 40 percent will be snatched up for the fresh market, the fruit that millions of apple enthusiasts will put in school lunches, or buy in the form of juice or apple sauce, even carve up for their own recipes – pie anyone? – or just grab out of the fridge or from the kitchen table for a quick snack.

The remainder is destined for processing, with some of those operations right here in Michigan (the Michigan Apple Committee lists some 14 on its website) and others located near other apple producing markets.

One local example is Heinz North America’s Holland operation, which uses Michigan apples to make vinegar.

One local example is Heinz North America’s Holland operation, which uses Michigan apples to make vinegar.

Other Michigan producers include Comstock Park’s Aseltine Cider; Burnette Foods, whose Hartford operation makes cider, applesauce and pie filling; and the Knouse Foods Co-op in Paw Paw, where frozen slices, diced, puree, canned slices, spiced rings, fresh slices, pie filling, concentrate and even apple essence are added to the mix.

The production process includes removal of the external surface dirt and topical chemical residues, and a water washing (often accomplished as the fruit is flumed from receiving stations to processing lines). Processors will sometimes add a form of chlorine compound to control build-up of microbes in the water before juice is extracted from the fruit and heat-treated (pasteurized) to kill any microorganisms, which also helps improve the overall clarity of the juice.

A typical apple generates about ¾ cup of apple juice or ½ cup of sauce, with one serving estimated to deliver 120 calories.

As recently as 2007, the average U.S. consumer ate about 17.7 pounds of fresh apples and another 29.4 pounds of processed – about 47.1 pounds of apples and apple products in total. That was up slightly from the 46.5 pounds consumed in 2003.

Also in 2007, 42 percent of apples that were processed were used for juice and cider. The next largest category was canned (35 percent). Other uses included baby food, apple butter or jelly, vinegar, dried, frozen and fresh apple slices.

But that 40/60 split between fresh and process is on its way to a near 50 percent split as demand for fresh fruit increases.

While the variety of apple is part of what will determine the destination of an individual piece of fruit, so is when it matures on the tree along with the amount of sugar present, the firmness, seed and even skin color. That, then, is part of what goes on with the hand picked instant decision-making during that harvest. The term “ripe for picking” is, at this point, quite literal.

Even so, picking doesn’t necessarily mean the apple will be used right away.

Storage is accomplished by removing the one element that turns a fresh apple into one that degrades over time. Think about that once-fresh apple in your fridge crisper to get the picture.

Storage is accomplished by removing the one element that turns a fresh apple into one that degrades over time. Think about that once-fresh apple in your fridge crisper to get the picture.

That one spoiling element is oxygen.

Smith says a process developed in Michigan has extended the supply of fresh apples by controlling the atmosphere in warehouses. “We basically put them to sleep,” she says. “They don’t continue to ripen but when we slowly reintroduce oxygen to the room, they can be sent to the packing line, which gives us a fresh supply for much of the year.”

Talk about agriculture and the subject of organic is bound to come up.

So how does this popular concept – at least among consumers – factor in to the world of apple production?

Smith says there’s not a lot of it, and for good reason.

“The problem in Michigan, at least as far as organic production is concerned, is we have a lot of water. And that means there are a lot of pests, which is a challenge for organic farming in the state,” says Smith.

Further explanation is clearly needed.

“Growers are not just conventional in the sense that they spray because they can,” says Smith. “We have a strong IPM system – integrated pest management – that includes going out into the field, scouting to see where there are pests and dealing with them on a spot basis.”

Some of that “dealing with it” includes a cute little technique known as pheromone disruption, essentially confusing the male of whatever pest is about to attack an apple tree into taking his amorous intentions elsewhere.

But when it comes down to it, Smith says the health benefits from apples grown organically versus using conventional agricultural methods are identical.

“There’s no nutritional difference,” she adds.

And from a carbon footprint perspective, conventional apple production may actually be better for the environment, given that organic farming includes spraying with non-synthetic compounds, which means spraying more often, which uses more fuel.

To your health

From the standpoint of health benefits derived from apples, the fruit is near iconic with its “apple a day” quip that every student (and parent) would likely still be able to finish.

Today, however, the subject is serious medicine, with numerous studies pointing to the benefits of consuming apples.

One, a clinical trial published in the June 2010 issue of the American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, described a study of patients in two Massachusetts nursing homes who received two 4-ounce servings of apple juice a day for a month with no additional changes to diet or medication. Patients receiving the juice showed significant changes in mood and behavior.

Improvements in anxiety, apathy, agitation, depression and delusion were most notable, although caregivers did not report changes in the patients’ cognitive performance or ability to perform day-to-day functions.

Another study, this one at Cornell University in 2005, pointed to the benefits of a diet rich in fruit, vegetables and whole grain foods. In the study, a group of rats with a known mammary carcinogen were fed the equivalent of one, three or six apples a day over a period of 24 weeks. The higher the number of apples consumed, the greater the reduction in the mammary tumors.

The Apple Products Research and Educational Council, an organization that counts the Michigan Apple Committee among its members, points to more than 100 research studies

that it says have helped inform the understanding of health benefits available.