The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) raised the federal funds target by a half percentage point to a range of three-quarters-to-one percent at their unanimous May 4 decision. This aggressive rate hike was the largest since the year 2000. Since then, the Fed had only hiked in quarter percentage point increments. Prior to the May decision, to avoid shocking financial markets, FOMC members telegraphed loudly in speeches and interviews that they saw a half percentage point hike as appropriate.

Chair Powell expanded on this guidance at a press conference following the decision. He stated that “There is a broad sense on the Committee that additional 50 basis point increases should be on the table at the next couple of meetings.” The Fed is likely to again raise their policy rate by half a percentage point at the June 15 and July 27 decisions; Powell said the Fed is not currently considering larger rate increases. He also said several times that the Fed will act “expeditiously” to lower inflation by raising interest rates to a level that is at least neutral (neither adding to or subtracting from growth), which most FOMC members believe is between two and three percent.

The Fed also announced a plan to shrink their balance sheet, which ballooned to $8.9 trillion dollars in early 2022 from $4.2 trillion two years earlier as they aggressively intervened in capital markets. Beginning in June, the Fed will allow up to $30 billion in maturing Treasury bonds to roll off the balance sheet (meaning they will accept repayment from the Treasury as bonds mature), and up to $17.5 billion in mortgage-backed securities issued by federal housing finance agencies (a.k.a. agency MBS). In September, the monthly caps will double to $60 billion for Treasuries and $35 billion for agency MBS. These amounts are caps, that is, maximums. The balance sheet will shrink by less in months in which maturing bonds fall short of the cap. This mostly matters for the Fed’s agency MBS holdings. The pace they run off depends on factors outside of the Fed’s direct control, like how many borrowers refinance their mortgages or sell their homes. While neither the May FOMC statement nor Powell’s comments discussed it, the minutes of the March FOMC meeting showed the Fed is likely to make outright sales of agency MBS beginning in late 2022 or early 2023, so that their holdings fall at a rate close to the monthly cap.

The Fed did not provide an end-date for balance sheet reductions. Instead, they said reductions will “slow and then stop… when reserve balances are somewhat above the level” the Fed plans to maintain longer-term. Practically speaking this means that the Fed plans to keep reducing the balance sheet at a $95 billion monthly pace at least throughout 2023, unless some unforeseen economic crisis causes them to reverse course and restart stimulus programs.

The Fed is raising rates much faster than during the long expansion from 2009 to 2020, when they took three years to raise the fed funds rate from near zero to a peak of 2.25%-to-2.50%. Near term, monetary policy will restrain economic activity more than during the last hiking cycle, with effects most pronounced on sectors like housing, commercial real estate, and durable goods spending. Chair Powell sees a “good chance” that the Fed can engineer a “soft, or soft-ish” landing from the current episode of overheating, meaning inflation would cool without a meaningful increase in unemployment. But Powell also said that the Fed is determined to slow inflation even if they are unable to avoid a recession, since a return to a strong economy with well-controlled inflation—like in the late 2010s—is only possible if inflation first comes under control.

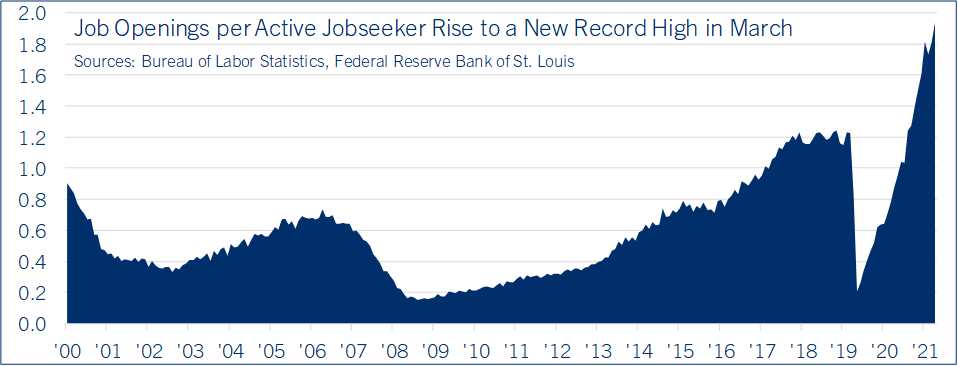

The Fed sees the U.S. economy as very strong right now. The FOMC’s statement and Chair Powell noted that, despite a contraction in real GDP in the first quarter, “household spending and business fixed investment remained strong,” the unemployment rate fell to near a half-century low, and there are more job openings per active jobseeker than any time in recent memory (See chart below). However, the Fed clearly see risks to the economy to the downside. The Russia-Ukraine war and China’s reimposition of rolling lockdowns are likely to prolong supply chain disruptions, exacerbate inflation, and weigh on U.S. exports. Comerica Economics sees the risk of a recession over the next two years as roughly one in three; the outcome of these foreign shocks will likely determine whether the U.S. economy merely cools or outright contracts (the first quarter’s fluky decline in real GDP, which coincided with employers adding over 1.5 million jobs to payrolls, doesn’t count).

Comerica is revising our interest rate forecast in light of Chair Powell’s more explicit guidance. We forecast for the Fed to raise the federal funds target a half percentage point at both the June and July interest rate decisions, and then by a quarter percentage point at each of the September, November, and December decisions. This will raise the target to a range of 2.50%-to-2.75% by the end of 2022. At that level, short-term interest rates will modestly restrict economic activity, cool housing demand, slow the growth of business capex, and make consumers less inclined to make big purchases on credit.

The 10-year government bond yield will likely hold near 3% near-term as the Fed begins to shrink its balance sheet, then pull back to around 2.50%-to-2.75% by year-end 2022 as markets fret over recession fears. Assuming no new negative shocks from Russia, China, or other foreign hotspots, real GDP growth will likely slow from 3.6% in year-over-year terms in the first quarter of 2022 to around 1.5% for the full year of 2023. That is below the economy’s long-term potential, but not a recession.

Bill Adams is senior vice president and chief economist at Comerica.