One of the most significant challenges facing America’s traffic snarled cities is managing the flow of vehicles, a growing problem in that the infrastructure challenges come at a time when population growth is outpacing the ability to deal effectively with need that comes with the growth.

Throughout the nation, the U.S. Department of Transportation is doing what might be called “selective surgery” as it identifies opportunities, typically brought to it for public investment, intended to at least make a dent in the problem.

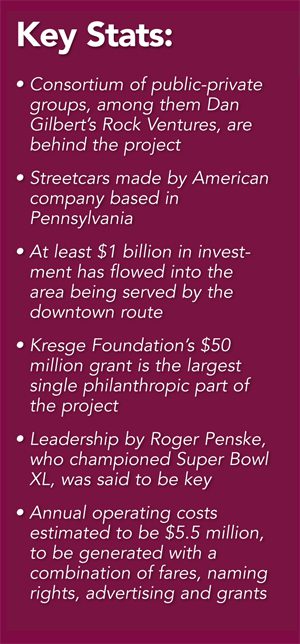

In Detroit, the opportunity came in the form of M-1 Rail, but the 6.8-mile loop, a streetcar project that will become operational in just a few weeks, may be different in that it’s not designed to unsnarl traffic.

Rather, it’s intended to bring more action to what has, over the years, become a near desert of economic growth.

That is changing with the promise M-1 Rail has delivered.

It’s been four years since Ray LaHood, heading the federal Department of Transportation, came to Detroit to announce a $25 million contribution to the project, which will run from Congress Street to West Grand Boulevard.

For the casual observer, the day the streetcars begin their circuit may seem like any other, but for others, M-1 Rail CEO Matt Cullen among them, it’s both a culmination of a project that was far from certain to ever exist and the beginning of a transformative redefining of not only the downtown Detroit area but, if your vision is big enough, the entire region.

In many ways it speaks to the power of inclusion and perhaps, in a broader context, why Detroit for so many years spiraled out of economic control and how, with a combination of persistence and philanthropic vision, M-1 Rail finally came together.

“We had a number of near-death experiences,” says Cullen, who in 2008 was hired by another Detroit-area native, Dan Gilbert, to head Rock Ventures, arguably the powerhouse behind M-1 Rail.

A year earlier, John Hertel, a former chair of the Wayne County and, subsequently, Macomb County board of commissioners, who was then CEO of the Regional Transit Coordinating Council, had recruited Roger Penske, founder and chairman of Penske Corp., to begin a visionary—perhaps too visionary—idea that would see a privately funded light rail project be built, seen then as the backbone of a future regional transit system.

Further pulling on that thread of history was one of the singularly historic events in Detroit, Super Bowl XL, which in 2006 underscored what was lacking in the region—a transportation infrastructure that in some ways put to shame a region that was, after all, considered the home of the American automotive industry.

But while the temptation may be to set that aside for a moment and focus on what has gone right, the reality is that at least a few of those “near death” experiences are instructive in their own right, highlighting the importance of staying focused on what is central to the vision of regional transportation.

But while the temptation may be to set that aside for a moment and focus on what has gone right, the reality is that at least a few of those “near death” experiences are instructive in their own right, highlighting the importance of staying focused on what is central to the vision of regional transportation.

In 2011, the team behind M-1 Rail, having agreed a year earlier to merge with Detroit’s plan for a light rail that would have cost a dizzying $528 million and run from downtown to 8 Mile Road, had the proverbial rug pulled from under it.

Funding that had been promised by local, state and federal officials was pulled in favor of a $500 million regional rapid bus line proposal.

But M-1 Rail backers, having assembled their own funding commitments—about $100 million by this time—lobbied for and secured a reprieve of sorts. That’s when LaHood promised the $25 million grant, provided the state approved a regional transit agency (RTA) for metro Detroit.

Even then, the project was hardly certain, although things were looking brighter.

One of those bright spots came in the shape of Kresge Foundation, the philanthropic organization that’s headquartered in Troy and which has committed a total of $50 million to M-1 Rail, the largest gift received.

One of the foundation’s lead proponents, aside from Rip Rapson, the foundation’s CEO, is Laura Trudeau, now retired as managing director of the foundation’s Detroit program, but who continues to consult on M-1 work.

“We want to bring jobs and economic opportunity closer to where people are,” says Trudeau. “Our mandate as a foundation, nationally, is to connect people to economic opportunity, so this fits very well with that.”

And while last fall’s millage rate proposal to fund the RTA failed (the federal grant required the establishment of the organization, not necessarily its immediate funding), Trudeau and others are hopeful now that M-1 Rail’s certainty is sealed, the likelihood of future taxpayer funding will improve.

“It’s really important to us that Southeast Michigan get a transit system,” says Trudeau, who sees M-1 Rail being the spark that could generate a momentum toward making that happen. “We saw a lot of energy talking about a catalytic project and having the rest of the system grow out of that.”

As far as the operation being able to continue without at least two years of RTA funding (the earliest that another vote could take place), the ability to carry M-1 Rail for the next decade has been baked into the business plan.

Eric Larson, CEO of the Downtown Detroit Partnership and another proponent of M-1 Rail, is someone who has a long history of involvement in the project, having worked on several projects with Cullen, a member of the DDP board (as is Cullen’s boss, Dan Gilbert).

“M-1 is one piece of a much larger system that needs to provide accessibility that comes in the form of bus, train, rail and bike share initiatives,” says Larson. “Each piece of that has a role, starting with hard rail. Any one solution on its own is fine, but we need that comprehensive network. M-1 is a huge opportunity to demonstrate that we’re serious about that.”

Another of the near-death experiences Cullen and others are certain to not soon forget relates to the streetcars themselves, the six units, each 73 feet long, 13 feet high and 8.5 feet wide, equipped with Wi-Fi, vertical bicycle racks and weighing 76,000 pounds.

Manufacturer Brookville Equipment Corp., located 81 miles northeast of Pittsburgh, Pa., wasn’t the first choice in a tendering for the streetcars. Nor was it the second.

It was Spanish vendor CAF that came out on top, but its technology for getting power to the vehicles fell short of what would work in Detroit.

A second choice, the Inekon Group of Czechoslovakia, was also subsequently set aside after problems began surfacing with its perceived ability to fulfill the contract.

It was then that M-1 turned to Brookville, a company originally formed in 1918 to manufacture wheels for railroad locomotives and, later,

vehicles used for coal mining.

But Brookville, when M-1 Rail began negotiating, was early in the game for producing a modern streetcar and had not yet delivered on a contract (since fulfilled) for a project in Dallas.

Still, people like Cullen had enough confidence to proceed with a contract, one that has resulted in actual deliveries of units.

“They had a lot of the technology that turned out to be very important to us,” says Cullen, referring to batteries that are charged from overhead wires on parts of the route, but power the streetcars for about 60 percent of the entire route.

“They had a lot of the technology that turned out to be very important to us,” says Cullen, referring to batteries that are charged from overhead wires on parts of the route, but power the streetcars for about 60 percent of the entire route.

Joel McNeil, Brookville’s vice president of Business Development, said in December that the company was two months ahead of schedule.

Brookville, as part of its negotiations with M-1 Rail, hosted executives, including Penske and Cullen, to view the firm’s factory, even as they approached the deal as something of a partnership, albeit one that came with a $32-million price tag.

“I think that’s how M-1 Rail approaches it as well,” says McNeil. “Our history is such that when both enter as partners, it drives overall success. That was certainly our attitude.”

The installation of the firm’s Liberty Modern Streetcars, now operating as part of a connection to the Dallas Area Rapid Transit system, was certainly a boost to Brookville’s fortunes, in that subsequent contracts with the cities of Milwaukee and Oklahoma City followed Detroit’s commitment.

“For us it was a continuing stepping stone, being able to implement these street cars across the U.S.,” says McNeil.

An important element in the procurement process was being able to meet the “Buy America” requirements set out by the U.S. Department of Transportation.

Those requirements included having suppliers ensure that 60 percent of the content of a product is from American suppliers; in the case of Brookville, McNeil says that percentage was “well over” 70 percent.

McNeil also said Brookville was the first supplier to have installed the “off-wire” system that is being used in Detroit, allowing the vehicles to be powered by battery for most of the route.

Other features of the streetcars include an automatic self-levelling system that ensures the vehicle, regardless of the number of passengers it is carrying, will always line up with the station platform.

Once the construction phase began in earnest, it was time for people like Bob Richard, senior vice president of Major Enterprise Projects at DTE Energy, to begin flexing their expertise in what it would take to make M-1 Rail a reality.

But work, says Richard, started a year earlier when the “go” decision was made to proceed with the project.

What quickly dawned was that this project would be substantively different from any “normal” one that may have been tackled.

Richard calls it a “marvelous collaboration” that occurred between DTE, the city, various utilities, and the Michigan Department of Transportation, which has authority over Woodward—said to be the first section of concrete highway in the nation.

A critical consideration was the understanding among those involved that essentially rebuilding the road and adjoining infrastructure would have to be done in a way that would allow future work to be done without disruption.

“We had to make sure that we would avoid future disruptions in service because that would mean digging up the rail, which obviously couldn’t be done,” says Richard.

“But the other thing we ran into was that Woodward Avenue is old—150 years old—and there were unmapped utilities, abandoned steam lines and underground storage tanks that no one knew were there.”

What DTE did was to design and construct conduit banks that contain compartments, a strategy that gives those involved with future projects the flexibility to upgrade features with minimum effort.

Another forward-thinking initiative was DTE thinking ahead to what would be required to add the four new substations it will need to feed buildings in the next five to 10 years, as investments in the midtown and uptown sectors further transforms the development landscape.

DTE took on the project management lead for the work to be done, working with the city and the Public Lighting Authority, the state-created body that is separate from the city in its mission to improve, modernize and maintain the street lighting infrastructure.

Richard says the work done by DTE, which ranged in cost from $10 million to $20 million, included what he describes as an “orchestrated dance” involving everyone involved in the construction.

“It was more chaotic and costly than expected, but it was also refreshing to me as a project manager to see how wonderfully people worked together,” says Richard.

It was November 11, 2016 when the final pieces of rail were welded into place, marking the end of what is now being called the QLINE—the result of Quicken Loans having secured naming rights. Gilbert’s company is also one of 20 station sponsors along the line.

Testing of the streetcars continues in in 2017, that process having started in early December.

But Matt Cullen is already convinced, especially as he notes the investments that have already occurred, even before the QLINE is operational.

“There’s been well over $1 billion in investments made,” he says. “That’s a big deal for us.”