This a multifaceted story, one that includes one of America’s iconic brands, an avid race car aficionado who earned his stripes for nearly 20 years before returning to the third generation family business, and saving that company from what might have been decay and failure had some of the lessons he learned not been put in place.

The company is Chelsea Milling Company, based in the eponymous city of 5,000 that is also home to actor Jeff Daniels and his Purple Rose Theater.

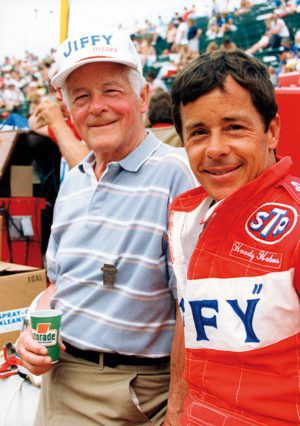

But current CEO Howdy Holmes is likely someone who’s had more of an impact on the Chelsea Milling Company and its 350 employees than almost anyone.

Born Howard Samuel Holmes in 1947, Holmes remembers annual family outings that would include a trek to the Indianapolis 500 as a teenager.

As early as age 16, Holmes remembers announcing to his parents on one trip to the Brickyard that he was going to be a race car driver.

“I had no idea how I was going to do that,” he says today. “But the seed was planted.”

A few years later, when the Michigan International Speedway was built (its inaugural race taking place in 1968), the owners sent brochures about a “racing school” to households in the outlying areas.

The Holmes’ household was one of those, Chelsea being only 25 miles from the racetrack, and 21-year-old Howdy grabbed it with enthusiasm, although he was attending Eastern Michigan University at the time (he did not graduate, but in 2012 he spoke at the school’s commencement ceremony and was presented with bachelor’s and doctorate degrees).

Holmes, who had worked at Chelsea Milling since 1963, the year he could drive, had found his new career. He enrolled at the driving school, bought a Formula Ford open-wheeled car from a local distributor and a set of tools, the toolbox for which he still owns. He then embarked on what became a 17-year career that included mostly road racing, one of the most common examples being various Grand Prix circuits that took place in North America, South America and Europe.

Holmes, who worked out of nearby Stockbridge, Mich., competed for the first time at the Indianapolis 500 in 1979, earning “Rookie of the Year” a year before he was the North American Formula Atlantic champion.

His last race at the Brickyard was in 1988. His final race, before finally completing a self-established five-year “exit plan” from racing, was the same year, at the Nissan Indy Challenge at Tamiami Park, part of the CART IndyCar World Series.

As early as 1983, the year he met his future wife Carole, Holmes had begun preparing for a return to the business of milling (he’s quick to point out that racing offered the discipline of business in its own right).

Carole and Howdy were married in 1986, a year after he was hurt —“badly,” he says—the result of a race car losing a wheel, flipping over and burying his head in sand for at least a few moments.

A rewarding career comes to an end

Overall it had been a good career for Holmes, with stints as a color commentator on ESPN toward the end, but always with the belief that he would return to Chelsea and the family business.

In 1988, their only son, also Howard Samuel, who is now involved in the business, was born.

Even while he was wrapping up his racing career in 1988, Howdy had reinserted himself at Chelsea Milling, becoming one of three vice presidents in 1987. The other two VPs were his brother and sister; all three siblings reporting to their CEO father, who couldn’t (or wouldn’t) set in place an explicit succession plan for the company.

What Howdy saw was a business that hadn’t kept up with the world around it, and that was something that was both concerning and frightening.

“The no-investment part was concerning, but the fact that no one could see it was frightening to me,” he says.

Holmes, who had succeeded in motorsports as a result of what he describes as “aggressive behavior, on and off the track,” says he found himself committed to do his very best to make sure Chelsea Milling would not succumb to the fate of most family-owned firms, which is that 70 percent are sold or fail before the second generation can take over.

“It was not going to happen if I could help it,” says Holmes.

What happened next is a part of the story that Holmes will tell, but with reluctance. Airing dirty laundry is not something he’s comfortable discussing.

Still, he recognizes the lessons to be learned by generations coming after him, including his son who now works in marketing and sales with the firm, not reporting to his father but being immersed in the business at every level.

“He wanted to work here since he was 12, but I told him he had to do something else first and he did. He came back in 2013 and he now has access to any type of meeting there is. He’s very mature and I think that comes from being an only child.”

On Howdy’s return, he set to work on a program of reform, a time that he says “was unpleasant for a lot of people.”

He was, he says, someone who may have appeared to some family members and some employees to be a wild guy. “To others, I might have been more a ray of sunshine,” he says. “And there were others who would play both sides of the fence.”

He was, he says, someone who may have appeared to some family members and some employees to be a wild guy. “To others, I might have been more a ray of sunshine,” he says. “And there were others who would play both sides of the fence.”

Howdy says he knew what had to be done, even in an environment where the CEO, his father, was, if not reluctant to change, certainly not embracing it.

But Holmes created list after list of things he knew were necessary, coding them to keep track of what steps needed to be taken, including references to “told Dad” and other key steps along the way.

“What made it complicated was the personal battles that were going on, the family disagreements,” says Holmes. “It took its toll in setting strategic direction for the company, which was very difficult for our employees, who frankly had more to lose.”

Change done incrementally

What Holmes quickly realized was that he had to implement the kind of changes he felt were necessary to breathe new life into the company, like outside directors on the board of directors, fully functioning accounting systems and other basic elements of any major business that existed elsewhere.

“I just kept going,” he says. “Remember, I couldn’t possibly be doing these things without everyone knowing about it, including my father, but he had an opportunity to stop me, so I felt with him not putting his foot down, I had tacit permission and I kept upping the ante.”

One of the “threshold” moments came in 1991, when Holmes succeeded in hiring a recruiter to find a specific person for a task, the company’s first executive from outside the organization (or the family).

Holmes remembers his father sitting at the end of the board room table, fiddling with his keys and not saying a word.

“He was giving away what he was thinking,” says Holmes. “And I was so spastic that I usurped the agenda and went right to new business, saying I would like to hire a CEO.”

At that point, Howdy’s father dropped his keys, his fist came down on the table and he stood, cheeks red.

“That’s the most preposterous thing I’ve heard in my life,” Holmes recalls his father roaring. “What would they do all day?”

Holmes knew the answer was that he could keep a professional manager busy 75 hours a week for years, but he knew better than to say so.

This is where some of the dynamics of the family enterprise came into play, one of those having to do with the company’s relatively new practice of adding non-family members to its board of directors. One of those was Wilbur K. Pierpont, a professor of accounting at University of Michigan who had served as a vice president and chief financial officer at the school before retiring from active faculty status in 1980.

“He was someone who was very highly respected, the kind of person that was essential when it came to having Mom and Dad accepting the idea of a board of directors made up of people outside the company,” said Holmes. “And who didn’t respect Wilbur?”

Another shift in the landscape as far as the business was concerned was the price increase that Holmes engineered.

‘Value’ vs. ‘cheap’

“We hadn’t had a price increase for eight years,” he says. “What I was worried about was that the cost of our product was getting ready to fall below the level of value into the realm of cheap.”

Holmes clearly knows not just the economics of the system but the history of the company and how its signature brand, Jiffy Mix, was perceived in the marketplace.

“Our target is working class Americans, who look to our product as value, a way to sustain themselves in a way that makes the most sense and which provides the best deal for them as they stretch their food budget. If we were to go below that ‘value’ level, word of mouth would kill us in the marketplace.”

This is a market, by the way, that relies exclusively on word of mouth, since Chelsea Milling uses no couponing or advertising.

“It’s a conscious choice for us,” says Holmes, “but it’s also one that gives us a strategic advantage, allowing us to offer our product to the end user for less money than the competition.”

Holmes remembers the day he had a pivotal discussion with his father, one where a philosophical discussion was taking place.

“Let’s just say our toes were very close together and our foreheads. And we weren’t amorous,” says Holmes, who also recalls one of his father’s favorite sayings.

“He said, and I totally agree with him, ‘we’re here to serve Mrs. Smith’ who he used as an example of our customer. Fortunately I said to him, ‘I agree with you. But if we’re not on the shelf, how are we going to serve Mrs. Smith?’”

That, apparently, was the end of the discussion.

“It was the first time I can remember there not being a response,” says Holmes. “He didn’t say ‘good point’ but he did so by not saying anything.”

A few weeks later, Holmes put in place an across-the-board price increase, waiting two weeks (which was the time it would take for the news to hit wholesalers, meaning it was too late to rescind it) before telling his father, who he met with at the family home.

“It was a horrible moment,” says Holmes. “He didn’t say a word, but that was something in itself and it probably saved the company.”

Holmes’ eventual escalation to the role of CEO in 1995 occurred as the result of several factors, including acting on discussions held with family business consultants on issues of succession.

“We finally started talking about some things that we’d swept under the carpet,” says Holmes, who had already spent at least some time acting like the CEO, albeit even while his father was in the titular place of authority.

Expansion continues

Today, the company is continuing an expansion it began in 2008 when it entered the food service and institutional industries, perhaps in large part due to a decline in the home baking market.

In 2013, Chelsea Milling announced a new $6-million research and development facility that will open in the fall of 2017.

The company now markets some 19 mixes, distributed across the U.S. and 32 other countries. While privately held, the company is said to have about a 65 percent market share in the prepared muffin mix category and a 90 percent share of the corn muffin mix market.

Having survived three generations as a family business and at least positioned the firm to ensure future success for at least one more generation (represented by his son), Holmes says he’s grateful for having had the opportunity.

“I was going to do everything I could to avoid the firm becoming the K-Mart of its day,” he says, referring to the once iconic retailer which is now a shadow of its former self. “I’m just grateful that we had the employees and customers who believed in what we stood for then and who stand with us today.”